I was looking for a topic for this week as I made my way into the office this morning. Shifting gears back from having the security of the next Tarot trump has been a bit more difficult than I thought, especially when it coincided with the Labor Day Weekend, short weeks, impending projects, new arrivals in the household (furry ones) and healthy doses of Mercury retrograde impacting technology and logistics on a grand scale.

A rested mind (and I am truly a mind in need of a rest) might find fertile options blooming forth in everyday encounters. This was much what I was doing last year, and I am confident I can wiggle back to it, especially if I get that rest I am talking about. This however is the start of my busy season, so resting never quite seems to actually arrive.

Ultimately it is the season that impressed itself on my this morning. As I drove down from suburbia to the quasi-industrial area of my day job, I noticed subtle, but apparent, changes in the leaves.

The Texas coastal plains lack that broad biodiversity of New England’s deciduous forests. And here along the Gulf, winter is more of a quaint notion (usually) than real alteration of the environment. Nevertheless, there are signs that in some of the trees the sap is beginning to retreat, and the leaves are going from green to yellow, and thence to less brilliant russets or scarlets, before dropping off.

I had always thought this transformation was a factor of temperature, but following one of the hottest summers on record, our descent into September has only meant a grudging movement from the 100s to the upper 90s daily. While it’s a drop, and for those of us living down here almost a cold snap, it certainly shouldn’t trigger any biological processes. So I started wondering what the trees knew that we didn’t , and how it might be that they knew this.

According to the U.S. Forest Service (and presumably they checked with the trees) the trigger is not temperature but light. The length of daylight, which gradually lessens from the Summer Solstice down to the Autumnal Equinox (in a few days), impacts the production of the green chlorophyll in the leaves. Chlorophyll is that magic substance that binds the carbon in carbon dioxide with the hydrogen in water to create simple sugars. These chemical factories are what make plants food for animals, and they are solar powered. So when there is less sunlight, there is less chlorophyll, and the leaves start making other chemical which produce the different colors.

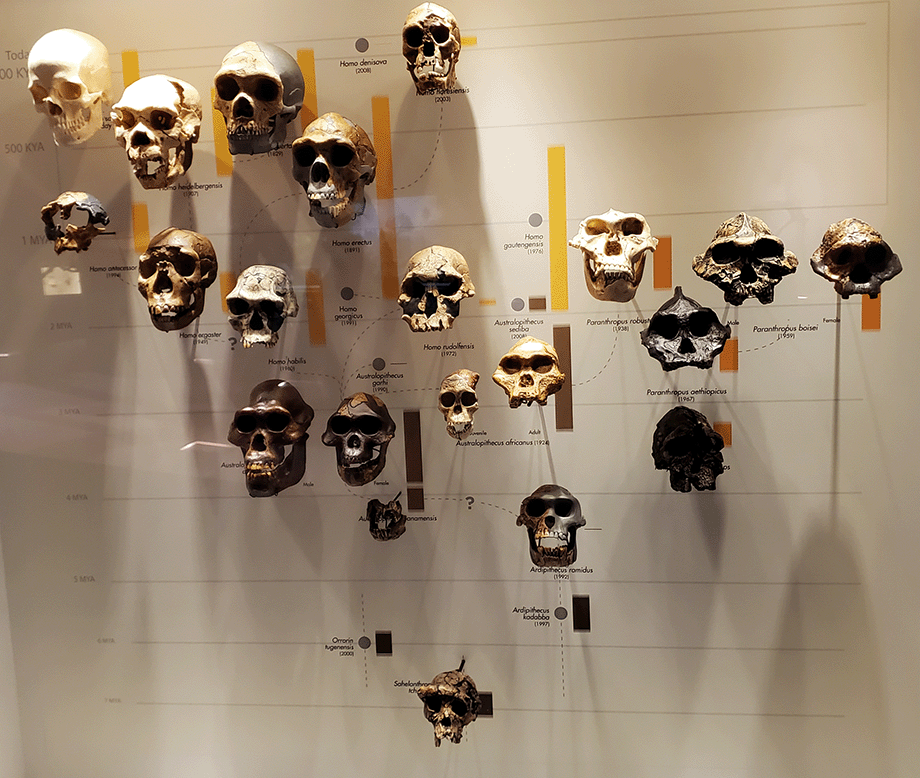

So basically, we have the changing colors in the trees because the nights are getting longer. Trees are astronomically controlled. This all seems very logical and sensibly scientific once you know, but ponder for a moment how many billions of years were involved in coming to this very efficient arrangement. The trees that will wow tourists in Vermont and New Hampshire began as simple one-celled organisms untold ages ago. Some of them drifted nearer the top of an ancient sea, and through a quirk of chemistry started to make the green pigment that sucked carbon dioxide out of the air. These basic creatures are still with us in the form of algae, though they can form much more complex systems now like kelp.

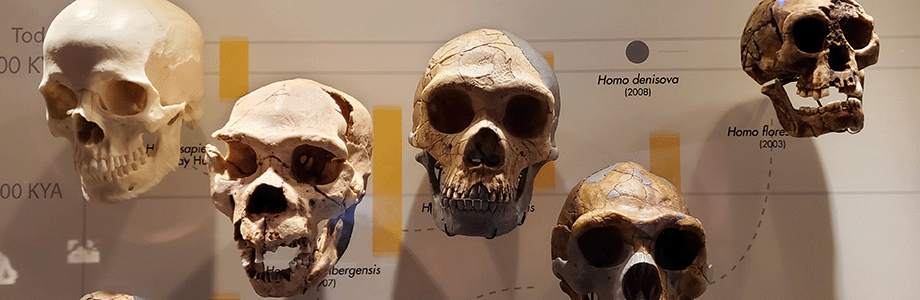

Their contribution in removing the carbon dioxide and releasing the free oxygen made it possible for other little critters to survive. These eventually became the proto-animals, similar to jellies that inhabit our oceans. The jellies developed specialized cell structures, and mutated to become corals and anemones and worms and mollusks and so on an so forth until we arrived to marvel at the changing of the leaves.

So despite shifts in climate, weather patterns, pollution, deforestation, wildfires and all the thousand natural shocks that forests are heir to, the trees keep looking to the sky, and repeating this ancient cycle of growth, death, and rebirth as the planet wobbles around the sun each year.

There’s a comfort to that. This cycle is something it may be very hard for humans to break. Despite all the abuses we heap upon Mother Earth we have, as yet, been unable to stop the sun from shining.

There are, however, other things that can. Some of them are right here on the planet, and some of them come from out there in the dark.

On the earth, the effect of large volcanic eruptions putting tons and tones of dust and ash up into the atmosphere have documented effects on the cycle of seasons. It is not just a drop in ambient temperature, as the scattered debris bounces light and heat back into space. It is that drop in light that tells the trees that winter is coming, that has a significant effect.

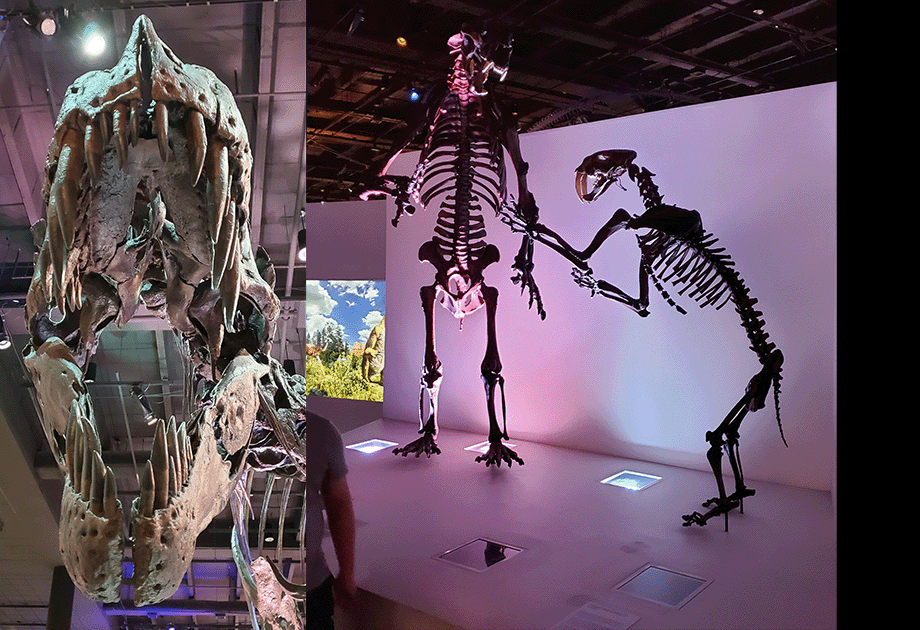

Likewise, the earth and rock and water vapor thrown up into the air by an asteroid collision can create periods of false winter that last for years or even decades. We believe that some of these events may have ended the age of dinosaurs, because the abundant plant life that made big heavy herbivores possible simply failed to wake up. Without the big heavy herbivores, the big heavy carnivores starved, and the mode of life became smaller and more efficient. Life mutated away from scales and feathers and eggs as dominant to fur and skin and wombs.

As the debris gradually dropped back down to earth from these events, the green plants bounced back, and ultimately big life forms were again fashionable, though the early mammals never got back to dinosaur scale. The few remaining giants we have are small (for the most part) in comparison to their ancestors. The elephant is impressive, but not so much as the great wooly mammoth. The grizzly and polar bears are certainly terrible to us, but the cave bears that stalked our ancestors were bigger still. It’s fairly clear, then, that the conditions conducive to big herbivores and big carnivores are starting to shrink again, without drastic events like super volcanoes and asteroids collisions.

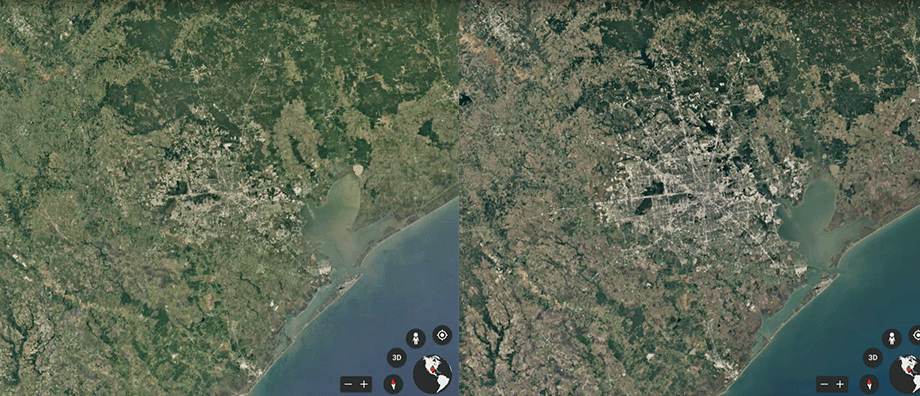

The new force eradicating the green biomass is human expansion. On my drive to work daily I see another area that was forested clear cut to put in another subdivision, or worse, a complex of warehouses and industrial spaces.

This latter exploitation is most harmful, because it produces acres and acres on non-permeable asphalt, concrete or hardpacked stone. The monster facilities now ring the city of Houston and show no signs of stopping.

Where once rain fell onto upper leaves, then lower leaves, then a floor of fallen leaves and decomposing wood, before percolating into soil, it now splatters across indifferent silica, before being rapidly funneled into gutters and sewers that fill the bayous faster than the grade can drain it. This results in increased flooding. To combat this, the watercourses are dredged, speeding up the removal of nutrient rich soils, and increasing the speed in which industrial and agricultural run-off are reaching the oceans.

In the suburban developments, the same thing occurs on a smaller scale, but it is no less harmful. Lawns and landscaping introduce an artificial ecosystem that must be maintained artificially, with pesticides and fertilizers and forced watering.

Human populations continue to grow and place more demands for food and housing and rapid Amazon delivery that drives this destructive cycle. The pandemic has massively altered our distribution model in the United States and the net result are these massive storage facilities “convenient” to the neighborhoods that spread outward from every city and town.

We are browning the planet with our building. It is not enough to blame fossil fuel use and the automobile for this rapidly growing issue. All these fields of concrete reflect heat. These human-made deserts are orders of magnitude warmer than a surrounding woodland or grassland would be. The heat impacts the ability for rain to fall. It is causing local climate change and may be responsible for the record highs we are all experiencing this summer.

I don’t have a simple solution. I know that there is not a simple solution, and that is what is holding us back from working on more complex ones. “Going green” involves changing our human mindset, globally, as a species, and I am not sure that is possible. We are wired by evolution to be acquisitive. We are built to consume resources and driven to become better at it because back in the days when Oog and Groont came down from the trees that was what kept us alive.

Such acquisitiveness and the unchecked growth it creates frequently has caused the periodic collapse of social orders. Civilizations rise and fall, and much can be attributed to the overextension of the natural resources that such populations require to be sustainable.

But we are now approaching a truly global civilization, and the limits of the planet to sustain it are finite. We can’t simply expand, like the old empires did. There is no where left for us to go, realistically. The sky is our limit. Even if we dream of colonizing the planets and moons of our local star system, the resources required have to come from this already overburdened planet we inhabit.

There are two outcomes to this situation.

We can, as a species, learn to live more responsibly with the planet we inhabit. This requires a fundamental chain in our habits, our politics, and certainly our economics. I don’t know that this will happen in my lifetime, even though I expect my lifetime to be longer than my ancestors. The pace of changing our ways compared to the pace at which those ways threaten to destroy us is not an optimistic picture.

Which is the second outcome. We fail as a species. Humanity dies out, like the dinosaurs, leaving behind maybe a few bones to be dug up in a hundred million years by whatever creatures evolve to replace us. It’s our species that is under the greatest threat from the mass extinction event we are feeding. We may not be the sole cause, but we are certainly a major contributing factor.

But when we are gone, there is every chance that the crud we have pumped into the air and water and the earth will eventually settle out, be buried deep, and the trees will start their cycle again.

It’s not about us.

I’ll be back next week.