One of the programs I listen to habitually is Your Average Witch Podcast. The format used by host Kim is somewhat unique (at least with regard to podcasts I follow). She poses to each guest a series of the same questions. Aside from getting to hear the guests’ answers, I find it often sets me wondering as to how I would respond as well.

One of the questions always asked of guests who (or what) are the top three influences in their magical practice. This question got me thinking.

You probably have ascertained that many of my influences are not the authors and personalities of the 90s and later decades. Most come from over 100 years ago. Chief among these is not an occultist in the strictest sense, but a scholar and translator from the British Museum named E. A. Wallis Budge.

If you’re not into Egyptology you may never have heard of him. His reputation is much abused in the modern Egyptological community. The general consensus is that his work is subject to significant error, and in particular his translations are flawed and poorly referenced.

I have read the newer translations of the Book of the Dead and find them substantially similar. Perhaps some of the pronunciations of the symbols have changed, but considering the language had not been spoken for say, a millennium, before anyone tried to decipher the written texts, it’s hard to say what it sounded like.

There are a number of people who practice a form of Ancient Egyptian religion today. I am not one of those. Nor do I work with the pseudo-Egyptian rituals out of the Golden Dawn and other ceremonial magic lodges. But my view of the cosmos is definitely shaped by the many books that Budge wrote, translated (if poorly), and preserved for our modern era.

While there are some good arguments that his translations don’t meet current standards, I find it more concerning that they are deeply tainted by Victorian Imperialism and Church of England Christianity. Yet, if you can find any text from that period that isn’t, it would be indeed rare. That is simply how things were.

The people who had the money and resources to research other cultures were inevitably going to put their slant on what they found. The myth that we do not do so today is ridiculous. We are, after all, evaluating those troublesome Victorians in the context of our current culture that is striving to overcome imperialism and monolithic patriarchal ideologies.

While there is no question that from the 16th through the 20th century, Europeans plundered the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and Central and South America for their ancient artifacts and cultural heritage, the collection of these things into museums has preserved them, and made them accessible to people who could never have visited them in their original location. Some of them were unknown even to their own people until an ambitious conqueror arrived with spade and shovel.

Ham, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons

Someday, it may even make possible the return of these artifacts to the lands of their creation and the custodianship of the descendants of those who made them. It is all well and good to support this principle, yet in my own lifetime great atrocities have been committed against art and artifacts in times of war. Plundered objects go to private collections of the uber-rich and never benefit anyone but a single person’s vanity.

So I have no problem with the large number of Budge’s books in my collection. After several decades of my own personal growth and experience, I am able to read past the taint and still find the magic and wonder of the original documents he has compiled from Egypt, Assyria, and Babylon. These texts, in the form that Budge wrote them, have been used by occultists and magicians from his time down to our own. They were the authority on the subject, and once inculcated into the magical tradition, their authenticity or interpretation was not again questioned.

And it is in the occult sense that I reference these works. I have books by Peter Tompkins, Howard Carter, Bob Brier, Kent Weeks, Zahi Hawass, Kara Coonie, and Peter Weller that offer very different views of ancient Egyptian history and culture. Archaeology is an evolving science, and new evidence can change what we have held as true for decades.

But the occult is much more forgiving when it comes to “facts”. If there are hundreds or thousands of occultists who have used Budges glyphs for the last century or so to write spells and inscribe objects of power, then those versions are the one’s being put out into the universe to manifest.

One thing that is relatively unchallenged about Ancient Egyptian culture is the emphasis on the power of these glyphs. Cecil B. DeMille in the 1956 The Ten Commandments gives the line to Yul Brenner as Ramses the Great :”So let it be written. So let it be done.” This underscores the value placed on the written word, and the hieroglyphic texts even moreso.

Most ancient Egyptians were not literate, so the glyphs covering every object and artifice were lost on them. But they knew it was magic. It was power. The glyphs were there to record for all time the works and deeds of Pharaoh, thus making him immortal. His named carved in stone would last, he hoped, for all eternity. This belief was so strong that many Pharaohs were cursed by having their names removed from temples, tombs, and sarchophagi, thus dooming them to oblivion. Some notable personages consigned to this fate were Hatshepsut, the Female Pharaoh, Akenaten, the Heretic, and his short-lived successor Tutankhamen.1Curiously all of these were erased by Seti I and his son Ramses II (the Great) in order to establish a new dynasty free of tainted bloodlines. Seti had been a military officer with no royal connection, so the need to establish his descent from Amen Ra was political as will as spiritual. By removing, hiding, or sometimes overwriting the names with their own, Seti and Ramses effectively deleted their entire reigns from reality, at least as far as Egyptian belief was concerned. This is one of the earliest examples we have of revisionist history, though it probably was practiced before Seti. It just may have been done so effectively we will never know it. The redaction of the latter king was a lucky break for him and for history, because his tomb was lost to obscurity, and thus remained unplundered until Carter’s discovery in 1927.

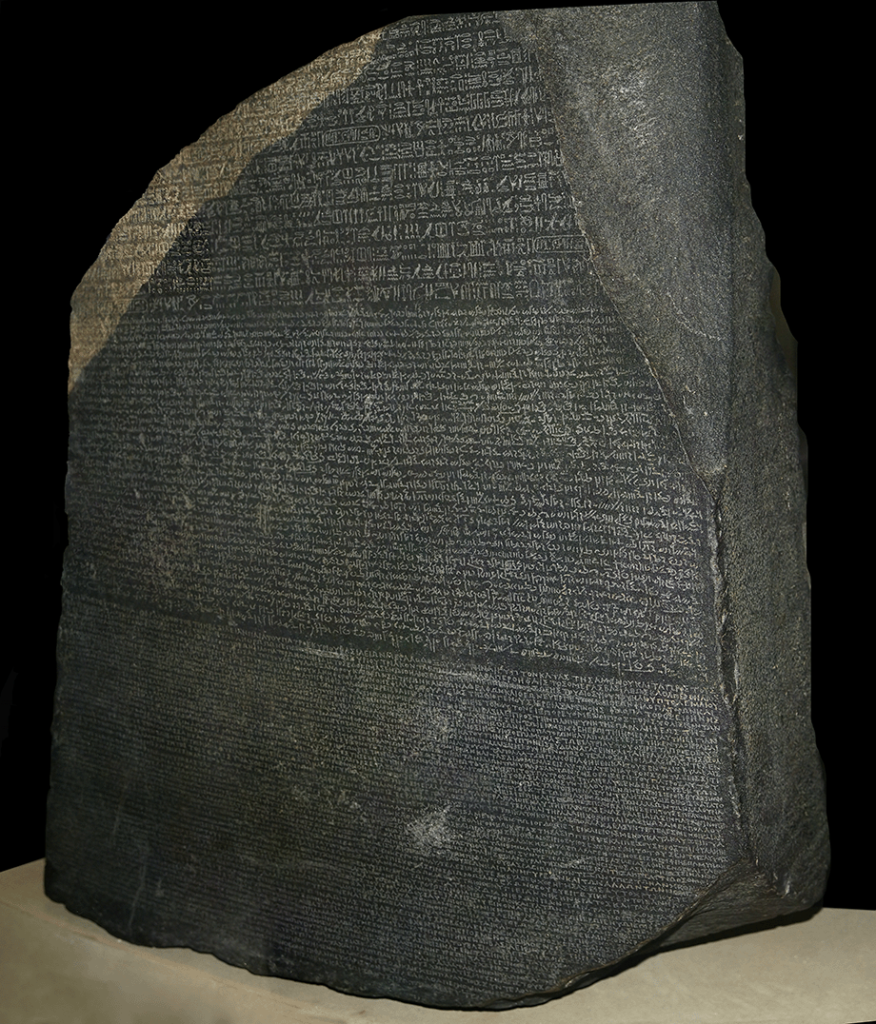

Ironically, the clue that allowed Champollion to break the code, was the need to write the Greek names Ptolemy and Cleopatra in ancient hieroglyphics. Determining that the glyphs surrounded by the loop of the cartouche were the names written in Greek and Demotic on the lower portions of the stone, he worked out which symbols were standing for sounds, and then went to find them on other artifacts. This would never have happened if Egypt hadn’t been part of Alexander’s Empire, and subject to the rule of invading foreigners.

By © Hans Hillewaert, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3153928

If we are to seek validation for using Budges bad conversions of the glyphs, and the potentially errant interpretations of gods, goddesses, and their veneration, we need look no further than that most troublesome of the Victorian magicians, Aleister Crowley. More specifically, we can hold up his Book of Thoth, as he calls the “Egyptian” Tarot. The word “Thoth” is a Graeco-Roman gloss of the ancient Egyptian name, Tehuti/Djheuty/dhwtj which refers to the ibis headed god of writing, magic, and sometimes the moon. It is this god who writes the names of the beloved of Osiris after they have passed the test of the Balance and confirmed that their heart is as light as the feather of truth. Thus written, they are eternal. Thoth’s book is the prototype from which all others descend.

We can see this idea of emanations in Qabalah, and it’s not surprising that Eliphas Levi made the connections between the Hebrew alphabet, the root of Qabalistic revelation, and the 22 cards of the Major Arcana. Levi’s confutation, without any real external facts, descends down into Waite and Crowley, and virtually every other Tarot system extant today. Tarot cards are a 15th or 16th century invention, which may have been used from the beginning as an oracle by many people, including the Romani, who were wrongly believed to be from Egypt. Hence this “ancient oracle” held the secret wisdom of the Book of Thoth, from which everything in the universe is made.

The Crowley Tarot is still in widespread use by Thelemites and non-Thelemites. I have at least a couple of decks, and a few derivatives. The designs by Lady Freida Harris are iconic, and offer a more modernist appeal than the sometimes quaint renditions of Pixie Smith or the woodcut Medieval harshness of the Tarot de Marseilles. But they are not, and never have been, Egyptian, or linked in any verifiable historical way with the god Tehuti/Djehuty/dhwtj.

This in no way makes them less useful as Tarot, or the alleged connection, any less useful in magic and spellwork. The gods still like hearing their names spoken, even when mispronounced. People have been calling to Thoth from Hellenistic times, and that has built a bridge the rest of us can cross.

In the middle we find Arthur Edward Waite, member of the Golden Dawn, translator and publisher of the works of Eliphas Levi, and writer of the Pictorial Key to the Tarot. His cards, executed by Pamela Colman Smith, are the most widely published, and will be moreso now that the designs have entered the public domain. Waite dismissed the myths that Tarot were an ancient oracle, but kept much of the interpretations of his predecessors.

Aleister Crowley was, like many Victorians, fascinated with Ancient Egypt and the discoveries being made there. He didn’t invent the idea that the Tarot are Egyptian, or represent an ancient occult Book of Thoth. That comes from a late 18th century writer named Alliette, who was elaborating on a “history” by Court de Gebelin with no factual basis. The interest in his theory was fueled by the importation of Egyptian antiquities by the European empires during that period. Crowley returned to the concept, layered on Levi’s Qabalah inferences, and married it to esoteric concepts he encountered in India and Asia (if not outright copied from Blavatsky).

We use their systems and interpretations today, though the meanings of the cards are gradually evolving to meet modern needs, and modern sensitivities. In a hundred years, the myriad decks published now may be more well known, and some industrious 22nd century chronicler will talk about how they were all derived from sources without any historical or cultural antecedent.

The important thing we need to understand is that when we cross that bridge, we don’t need to carry all that Victorian baggage. It’s not an expedition into the darkest jungles replete with racist stereotypes of native African bearers, submissive Punjabi manservants pouring Afternoon Tea and enforcing our White Imperialist Christian Righteous Rightness at the point of Sahib’s big elephant gun. So when we approach these texts, we need to learn to read past the inherent arrogance that sometimes works hand in hand with the ritual.

This arrogance is one of the problems I have always had with the compulsion of spirits -usually reckoned as demons, using the power of the Christian god. This practice is not exclusively Victorian, of course. They were parroting Medieval beliefs that derive from the Holy Mother Church’s dogma suppressing all other beliefs. There’s some evidence that Abrahamic religions supported this kind of thing, but it’s hard to say whether that was an original doctrine or some contamination from later influences. Certainly pre-Christian traditions used compulsion and exorcism rites to drive away unwanted spirits that were not pacified by more placative means. But this seems to have been more of a utilitarian approach, than assertion of a Divine Right.

The Victorians were the product of their time. India had been under British dominion for several hundred years by that point, and the boundaries of Nepal and Tibet were loosely defined. Egypt and Arabia had been in their control, more or less, since Napoleon was defeated. The Chinese Emperor had been declawed in the Opium Wars, and the ancient Silk Road had to pass through British Hong Kong. Aside from those uppity Americans, the people of the British Empire could consider themselves masters (and it was masters, despite Her Majesty the Queen) of the world of the 19th century.

When one sits in the center of that world, it’s an unfortunate tendency of human nature to believe in one’s own importance. People talk about Manifest Destiny and the White Man’s Burden and other foolish justifications for oppressing less technologically advanced cultures. They begin to believe that the ideas they may have pilfered from these cultures are their own invention, and rightfully theirs, because of who they are. It is only with the benefit of looking back from 100 years on, with a gentler perspective and wider awareness, that we can perceive their errors.

Or maybe not. When I started writing this article I was thinking about this massive blooming of occultism and spirituality at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, spurred by the horrors of the American Civil War and Crimean War in Europe, fueled further by World War I and the toppling of several European kingdoms, and the extreme social change wrought by the massive numbers of deaths during the Spanish Flu epidemic.

And then I look at the parallels of the later 20th century and early 21st, wars and rumors of wars, social upheaval, global pandemic, and a corresponding rise in new spirituality and occultism.

I am not here to claim that history is repeating itself. You can make your own choice there.

It’s fair to say that the ends of centuries seem to mess with our collective heads, as the end of the 18th included the American and French Revolutions, and sad stories about the deaths of kings. Our millennial event in 1999/2000 amplified this tendency that we as a species have to connect importance to dates on a calendar and then act as though something should be happening.

We are now in the unenviable position of becoming the next century’s troublesome Victorians.

There is an unpleasant undercurrent of extremist rightwing viewpoints pervading some pagan groups. Discussions of pure blood are creeping into ancestor veneration in places.

While giving lip service to making the new spirituality open and welcoming to persons of color, the economically disadvantaged, members of the LBGTQ+ community, and differently abled individuals, the core remains largely white, middle class, and neurotypical, using rituals and symbolism that connects to a binary heterosexual duality, frequently where one or the other partner is dominant.

These are the echoes of that 19th century arrogance. We are hopefully engaged in changing that, to make a better brighter world for all. But the Victorians believed they were making a better brighter world for all. That is the trap of arrogance, of sitting in the middle of the crumbling empire, and saying, oh, look how we can fix this.

I am as guilty as anyone of this arrogance. This little publishing enterprise is evidence of my confidence that my voice has value and should be heard. It’s not very different from the plethora of self-published magazines and books that we have from the late 19th and early 20th century on magic, spirituality, art, literature, and social change.

Nor am I saying that any of us should stop trying to achieve this change. It is vital that we make these changes.

But we have the advantage of well-documented hindsight. We know that in a hundred years, what we write and record and say today will be reviewed, dissected, appraised, interpreted and judged by whoever is leading the vanguard on spiritual transformation in the 22nd century. So we are able to consider how we want that posterity to remember us.

Are we going to be the carriers of the fire of a New Enlightenment, or are we going to be troublesome?

Thank you for reading to the end. I know my style of writing is more in common with those troublesome Victorians; the result of reading so much of their work, no doubt. I hope you will join me again next week for another trip down the rabbit hole. Peace and long life.

Instagram poster image edited from a photo by Alvesgaspar – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3259988