On Friday last I attended the Ordination to the Diaconate at the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart. We had been invited to witness the investiture of a friend. I am not Catholic and clearly not Christian, but I respect individuals who live their faith through tolerance, generosity and humanity, even if the “official” policies of the faith are problematic.

Besides, it gave me an opportunity to anthropologically observe a high ritual for comparison and contrast with my research on the nature of human belief. I had attended Catholic weddings and funerals before where an abbreviated mass and Eucharist had been performed along with the other rites, but this was the big show, conducted by a full Prince of the Church, and something I was very much interested in seeing.

Contrary to what you may expect, neither I nor the cathedral burst into flames when I crossed the threshold. And while I respected the requests to stand and sit (kneeling I don’t do, aside from the hypocrisy that would involve, my arthritic knees simply won’t accommodate that), I did not partake of the Communion. I will not profane another’s sacred rite by participating in it if I am not a believer. I was not alone, in that respect. Whether because they were not of the faith, or were, but did not feel the need to partake, I can’t say, but fortunately I was not the only person attending that skipped that part. Within that context, I found the whole experience immensely interesting and enlightening.

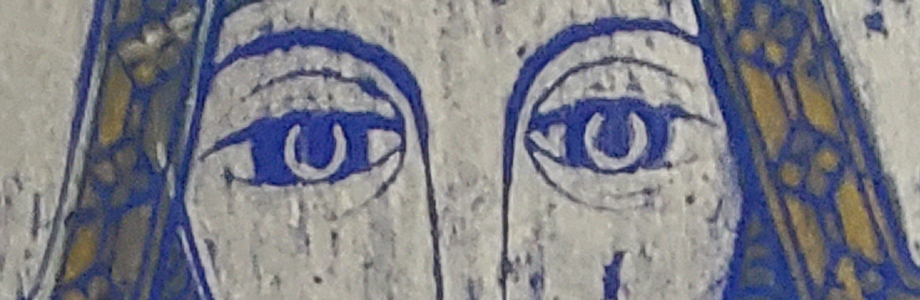

I’ve been fascinated by the symbolic toolkit of the Mother Church since art history class, and was actually a bit let down by the more modern and rather bland cathedral. I suppose it’s hard to be wowed after you’ve experienced the great Gothic edifices of Europe. This building had more in common with their predecessors in the medieval times. The space, though sufficiently massive to impress, was limited in decoration, and lacking the great glimmering mosaics or stained glass of the traditional churches.

In fairness, with the congregation much more literate, and with audio-visual tech for reaching those less so, the need for the great surface decorations as means of visual instruction in the mysteries no longer exists. To me, that is rather sad. The aesthetic experience of art, and the elevation of spirit and alteration of consciousness that art alone can provide, was missing here, or at very least subdued. Beneath the great dome of the crossing was a porphyry high altar, supported by twelve columns emblematic of the Twelve Apostles (and just perhaps the twelves zodiac signs). To the right of the dais was a matching lectern as microphones have supplanted the requirement of the raised pulpit. On the left a simple wooden podium was provided for non-ecclesiastical personnel, such as those leading the hymns and oratorios.

On the other hand this spartan space did focus more attention on the pageantry of the ritual itself, with the robed nobles of the church arrayed behind the high altar, the great gold and silver clad Gospel book poised upon it, the thurible and the incense wafting out over the crowd. With the aforementioned standing and sitting and kneeling and the calls and responses, hymns, the litanies of the saints, and other parts of the three-hour ordination ceremony, there was certainly a creation of a focused ritual space.

I believe I spotted a number of symbolic performances and structures, which I will not enumerate here, that seemed familiar. Having not attended a ceremony like this, and not having a Catholic background, these observations are perhaps inaccurate. That’s something we should all keep in mind when reading anthropology, or when sussing out a ritual from some old texts that may have been written by the outsider. As an outsider, though, I found that I could appreciate the sacredness of the acts, whether or not they personally were sacral to me.

Within this time and space, there was a clear feeling that something happened that non-Abrahamic monothesists would term magical. There was a belief, from the cardinal down to the congregants, that a power was moving through him into the supplicants for ordination, and that they were transformed into something different than they were beforehand.

As human beings we engage in ritual for both selfless and selfish reasons. Our need to feel there is something beyond that which simply happens to us daily drives a desire for communion with the Holy. Often this takes place in a public setting, where we share our experience with others.

Yet we can and do engage in very small individual rituals. It may simply be flipping our eggs the same way each time, while muttering some incantation to make our day “sunny side up”. This participation elevates the mundane experience and gives meaning to our actions. All our actions.

In sanctifying our every movement, we teach ourselves about the sanctity of all other things as well. In this way we learn how to relate to the world as sacred space, where each thing is a sacred act.

This, of course, is the idea behind any form of initiation, even those that are not wholly magical or spiritual in nature. That is perhaps why we encounter commonalities between many such rituals, and why some people believe that one group or another is stealing something that predated that group’s origin. I have heard much about how the church has appropriated rituals from Rome, Greece, and Egypt, and this is doubtless true. The Romans, of course, amalgamated Greek and Egyptian and Hebrew and Persian and Celtic and Gothic and Hunic and Punic and whatever else they encountered, so a nascent Roman church can hardly be castigated for following this model.

It’s fairly obvious given the similarities between the roles of the various deities in ancient cultures that they either had a common origin in some unknown past, or they represent a basic human tendency to explain our experience through animism. Or it can be both.

Recent discoveries at places like Gobekli Tepe and the region around Stonehenge indicate that our propensity for sacred ritual predates our agricultural civilization. That is, we were not holding a festival to celebrate the harvest, we learned to harvest to celebrate the festival. Sacred megalithic sites seem to have been built up over generations, because there was some local reason for people gathering there, and when they gathered they celebrated with feasting and drinking. To these stone-age peoples, the experience of drunkeness, or other altered states of consciousness, was not simply the result of eating the white berries, it was transportation to the realm of the spirits.

In the case of Stonehenge, the draw appears to have initially been a rich source of flint. In the Neolithic, flint’s role was the equivalent of petrochemicals to modern industrial society. It was used for hunting, of course, but it was also used for the preparation of food, the construction of housing, the production of hides, leather, and clothing, and, perhaps most importantly, the kindling of fire. Wandering tribes of hunter-gatherers would follow the food animals during the seasons, but at some point in each year they would return to the lands around Stonehenge to replenish their supply of this all important natural resource.

Such mining and refining probably took place at times when the food animals were going into dormancy, and the wild crops were dying down. So with the larders full against the coming winter, the tribes would head toward the mines, and when meeting with each other, appeared to join in communal feasting and ritual.

To insure full larders, the food animals and crops gradually became domesticated. One theory emerging from work at Gobekli Tepe is that grain crops were initially being cultivated to make beer. Considering that these beers could very well have been contaminated with things like rye ergot, or various other fungi and molds during the fermentation process, prehistoric brews may have been far more hallucinogenic than your average can of Bud Light today. Consider also that ancient humans had certainly discovered more powerful intoxicants than simple alcohol, and were possibly adding these, or using them in conjunction with, the ritual beverages. We find significant evidence of the sacred use of intoxicants and hallucinogens in the historical accounts of “stone-age” cultures that survived in isolation to modern times. Indeed, some of these practices remain extant among indigenous peoples despite the attempts of colonizers and modern legal restrictions.

When Christianity began to take hold over Europe in the fifth century, the elation and abandon of chemically augmented spiritual ecstasy became associated with the “old religions” and ultimately stigmatized and criminalized. The ritual pageants remained, and became central to the practice (if they were not already, let’s not assume that every pre-Christian rite was a Roman orgy) and spread out, in one form or another, as the One True Catholic Church split and splintered and rolled across the world.

And yet the chanted prayers, the sacred spaces, the processions of symbolic items and artifacts, can be found right through Islam, Judaism, and non-Abrahamic Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism and the various fragmented children of those faiths. We can locate a version of it in indigenous religions, in the Victorian magical lodges, the modern fraternal societies, and the graduation ceremonies in schools and colleges.

We as human beings have an inborn need for this sacredness. We, alone on the planet (as far as we know anyway) yearn to experience something greater than our mundane daily grind, to connect with that which is beyond and experience that which is other. Whether we attain to such states via all the pomp and splendor of a choreographed religious ceremony, or we approach it by contemplating the bubbles in our morning tea is irrelevant. The result is our internal elevation, that epiphany of self that leaves us transformed, and returned to the mundane world a bit different, and perhaps a bit better.

My eldest and I were perusing the occult shelves at a local used book store recently when she commented “These all seem largely… self-helpy…” I have had the same observation with many of the texts being offered in the last couple of decades. To be clear, it is not the idea of self-improvement that we find disagreeable, but the thought that it can be achieved by reading a few chapters of the latest hastily published thin paperback on magic, witchcraft, astrology, chakras, herbalism, crystals, or tarot. Much like the myriad diet and exercise books, and those psychology and pseudo-psychology books that are actual defined as “self-help”, many of the hundreds of texts under the broad label of “new age” appear to offer a quick fix for all that is wrong in the world.

And to be fair, like most of these books, there is probably a paragraph or two that mentions to be effective such changes and practices are a long-term commitment. Self-transformation is not a goal, it is a process. It is the result of small steps taken all the time, and over and over, and doesn’t ever stop. The road is long and winding, if one gets the opportunity to walk it. In time the little changes open up our minds and our hearts and gift us with the true realization that it is not all about us.

“Self-care” as a buzzword and marketing strategy has emerged to dominate a number of quasi-esoteric topics since the beginning of the plague years. This is an expected result of the kind of emotional trauma that this world wide epidemic, and the social changes it brought. But as we hopefully emerge from the Valley of the Shadow of Death, we have to be more than self-absorbed and self-contemplative islands. At the same time, we need to realize that we will feel isolated and alone in the cosmos, as we make the journey outward.

I have said before that the Hermit and the Hierophant both hold the secrets of the universe. At one time or another, we will seek revelation through either pathway, and there is no reason to choose one over the other, or to exclude one or the other for once and for all.

The Sacred Life is one that keeps us constantly moving forward.

And on that thought I will move forward to next week’s article, and thank you as always for your time and attention.