Owing to my Good Lady Wife’s completing certification last week at the National Fire Academy, we found ourselves in the vicinity of Gettysburg for the weekend.

For the record, we are history nerds. We have the shirts and the hats that say that. And we enjoy a bit of time travel now and again, as a break from the multifarious pressures that come with the responsibilities of our day jobs. So we had booked ourselves a lodging at an antebellum bed and breakfast for a couple of days wandering about the various historical landscapes.

I know when I was a student in school, the battle that took place in this area on the first few days of July 1863 was taught as a very significant event. That was some time ago, and our schools keep adjusting what is historically important. Perhaps that’s as it should be.

I am a great believer that history should not be presented with blinders on. Nor should it be controlled and coerced into serving any particular agenda.

Things happen. We all experience things happening. We are all traveling through time at the pace of now becoming next, and now became then, in exactly the same unrelenting instant.

And what we experience, and how we react to it, and how we remember it is an absolutely personal thing. So it is safe to say that we may view any event we directly experience very differently than another person who experienced it with us.

This is part of the otherness that defines our human existence. It’s a consequence of being part of a universe that wants to know itself and all it’s potential selves. We can only hold that passing moment in memory, and memory is purely internal.

The American Civil War, and the slice of it that is the Battle of Gettysburg, is one of those things that has so much impact that it’s still being “contextualized” over 160 years later.

As a proper history nerd I try to follow two basic tenets.

Firstly, information should be analyzed to the extent that any bias that is likely to exist can be excised from the data itself.

That is, if you know one account was written by a Northern Abolitionist and another by a Southern Slave Holder, the information needs to get pared down to times, quantities, etc. Certainly the perspective can and should be accessed, to give us all some idea of the human experiences and ideas involved, but it’s not history, it’s the way the author viewed history at the time.

Which brings us to the second rule, people in history cannot, and should not, be judged or understood by the modern views we now hold.

Our present sensibilities are vastly different from the combatants of the American Civil War, from the Spanish Conquistadors, from the Roman Centurions, or any other person that has lived in a different period of time. Social media is rife with commentary about the differences between “Boomers”, “Gen X”, “Millennials”, and “Gen Z” and this is just among generations that we’re born since the Second World War. How then do we have the hubris to presume we “understand” the motivation of an Antebellum population?

This is why I prefer time travel to historical research. As the Doctor has said, we time travelers point and laugh at archaeologists.

Time travel is not an easy thing to do, of course. Absent a flux capacitor, temporal rotor, or warp drive, you really are tasked with finding someplace where the forces that perpetuate the illusion of linear time are relatively weak. These are becoming harder and harder to find in a modern global world interconnected with telecommunications equipment. But you can find them. And you can learn to ignore the distractions that can remind one of calendar dates and modern tech.

Find the ghosts can help.

I’m still not sure personally if ghosts aren’t simply other time travelers. Certainly we have the stories of ghosts that echo the horrible circumstances of their deaths. To the spiritualist and medium these sad beings remain because of the trauma they experienced, leaving a permanent imprint, or the presence of an unquiet spirit.

But there are lot of ghosts who simply are seen engaged in the normal activities of their life, or perhaps engaged in an emotionally intense event, like a pitched battle. In these cases, it is not impossible that we are simply peering past the walls of linear time and viewing the events that are happening just over there in the cosmic everpresent.

Several of the ghosts I have run into in my life look just like regular people. They don’t look “dead”, still have their heads and hands and aren’t bleeding profusely. As they walk past, some of them nod and smile, just as we would if we met in the hallway or on the street inside the same space-time.

They’re just slightly outside that space-time, and as such these moments can be brief and end abruptly. Almost as soon as one perceives the true nature of the encounter, one turns to look again and they’re gone.

We understand about as little of the true nature of time and space as we do the nature our own spirits. The tangibility of the meat suit, and the apparently “real” material world it inhabits, is, even to modern physics, not an entirely absolute thing. Physicality as we experience it may simply be another illusion, a limitation our our perception of the universe around us.

Time and space in our dreams is nothing like what we live in daily. It is non-linear, it is certainly non-physical, and frequently defies logical causality. Imagination is as ephemeral, so it’s a very difficult proposition to prove that the existence of the mind is bounded by the physical world and the apparent flow of linear time.

If you’re not a history nerd, it may surprise you to learn that the Spiritualist movement has it’s roots in the period following the American Civil War and in Europe following the Crimean War a couple of decades later. In both cases, there was an horrific loss of life on a scale not experienced before. Many of the dead were lost far from home, sometimes interred in mass graves with few markers. And still others were listed as “missing” which means the bodies were never identified.

In the era before modern embalming had become viable, there simply was no way to ever bring these dead men home. Such methods as existed (and they were largely experimental) were open only to the rich, who had not lost their wealth to the fortunes of war.

This left loved ones with no sense of closure. Spiritualism, with the trappings of the séance, table turning, spirit trumpets and talking boards offered mourning survivors a solace that they did not find in traditional religion. With the belief that the dead could be contacted, a wider acceptance that they remained in semi-tangible form as visible ghosts became more and more prevalent. Soon, spirits and ghosts began to expand beyond the shades of those passed on to include the shades of things that had never been alive.

The “ghost” of Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train is a widespread story across the parts of the country where his final journey passed on the way from Washington, D.C. to Illinois. Even for the animist, it’s hard to expect that the locomotive and cars that made that journey are spending eternity repeating the trip, particularly since the ghost of Lincoln himself rarely features in the stories.

We can accept that this is a mass delusion, of course. We can say that the trauma of the war and the culmination of that in the assassination of the President created a national myth that caused people to see that ghost train.

Or we can suggest that this same trauma has weakened the walls of space-time in some locales, and that we are still seeing the train as it passed on that fateful trek.

The same may be said for the phantom patrols and the ghost battles and other hauntings reported at Gettysburg and other battlegrounds of the American Civil War. It is not an exclusive experience to that event, either. I had a friend tell me they had a similar response to the battlefield of Culloden, in Scotland.

When we spill that much blood and pain and hate, it may not be possible to close the wounds for a very long time.

Culloden was the end of the Jacobite Rebellion. Gettysburg, though the war would continue for almost another two years, would signal the ultimate defeat of the Confederacy. In fact, there is one moment that historians will point to as the turning point in the war. That is what is known as Pickett’s Charge.

On July 3rd, after two days of battle with territory changing hands several times, it looked as though the Army of Northern Virginia under Robert E. Lee had the upper hand. There were still a handful of entrenched positions held by the Federal troops, but if they were broken, and put to retreat, Lee would command the supply lines that fed into Washington, D.C. and capturing the United States capital would have been much more likley.

If that had happened, the Confederate States of America might have continued to exist for some time, been recognized as a legitimate entity by other world governments, and institutionalized African slavery continued for some time, financed by the desire to feed cotton into the burgeoning mills of the awakening Industrial Revolution.

Alternatively, the area of North America between Mexico and Canada might have splintered into a number of small nations similar to Europe. The Westward Expansion that followed the Civil War would not have occurred as it did, and the vast wealth of natural resources would not be harnessed under a single banner, but squandered and fought over for decades. Alliances and pacts like those that precipitated World War I in Europe would surely have similarly volatile results in the Western Hemisphere, and the Twentieth Century could easily have been marked by constant international warfare with very little progress.

I’m sure some of us could argue that the Twentieth Century was marked by constant international warfare, and frankly we don’t seem to be making much headway in the Twenty-first, but we sew the seeds and see what will sprout in the future. Time travel doesn’t always help us see what’s coming. Because it’s complicated.

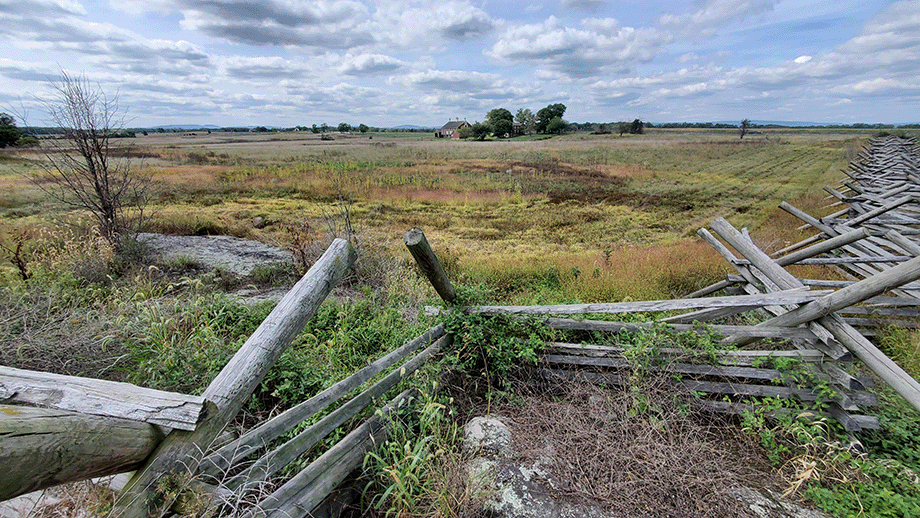

On July 3rd, 1863, General Pickett ordered his men forward against the enemy line, to “take the Yankee position” at a place called the Angle. To get there, they had to run down a rise across open territory, cross over a fence, a ditch, a road, and a stone wall, before reaching the enemy position.

If you stand on that terrain today, you wonder at what possessed them to attempt something like this. It’s clearly suicidal. It was a really bad idea. The commanding officers should have known that. They may have known it, but they chose to ignore it.

The din of battle is long gone, and as one descends into this shallow depression, it becomes eerily quiet. The birds stop singing. The crickets don’t chirp. There is nothing but the whisper of a lonely wind. The walls of time grow thin here. The land still weeps, despite more than a century and a half is past.

When Lincoln said those gathered to dedicate the cemetery located nearby had not the power to consecrate this land as deeply as those who died upon it, he may have peered behind the veil of time, and felt this long lasting scar. The Lincolns were early believers in Spiritualism, having lost a child at an early age. In 1865 the President related a dream where the boy took him through the White House to show Lincoln himself lying in a casket. He would be dead within a few weeks from a bullet to the brain.

We can analyze this and say it was the bravado of a Southern Empire drunk on it’s success and resting against the wealth brought to it by the subjugation of other human beings. We can assign a reliance on military training referencing the Napoleonic Wars as recent to Lee and his generals as we are to Viet Nam. Pickett, who survived the slaughter, responded when asked about why it failed said “I believe the Yankees had something to do with it.”

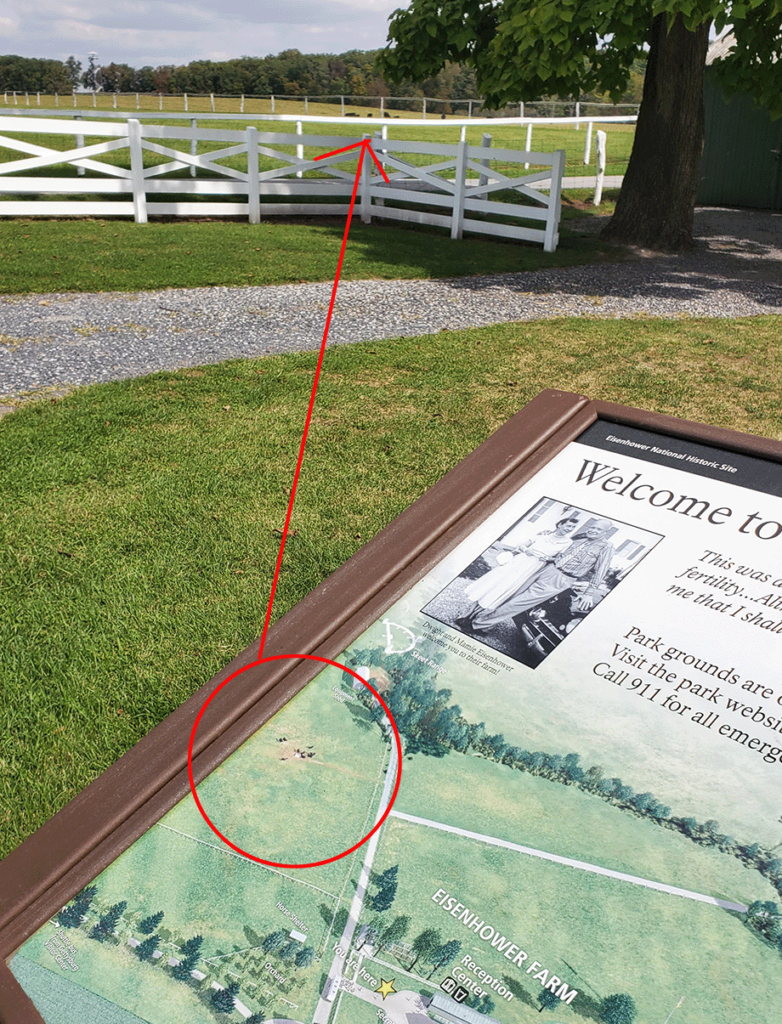

Not far from this site is a farm owned by former U.S. President Eisenhower. The period of the Eisenhower presidency is a source of much nostalgia in this country. During this time the more or less intact U.S. industrial complex was tasked with rebuilding both Allied and defeated nations. The economic growth was unparalleled, and propelled the U. S. A. to the top of the world scene, challenged only by an injured but pragmatic Soviet Union.

Eisenhower, before becoming president, was Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the European Theater of Operations. He is widely considered to be the primary architect of the June 6, 1944 invasion of Europe commonly called D-Day.

I did not have the opportunity to see the beaches when I was in Normandy back in the 1990s. I was there on business, and never got that far west. But I am familiar with what was called the Atlantic Wall.

I can only imagine Eisenhower and his advisors looking at the obstacles they faced. They had to land on an open beach, covered by machine gun and artillery placements, a vast trench and tunnel network, barbed wire, land mines, and heavy concrete obstacles. Should they survive that they had to get up cliffs in some cases, and then take those fortified positions.

If the assault failed, if they didn’t clear the beaches before sundown and make it possible to bring ashore more troops and tanks and supplies, then they might never be able to break the Nazi grip on Europe. The horror and oppression of the Third Reich and the Holocaust would remain unchallenged. The Allied Nations ultimately might fail, and certainly could not maintain against it.

It was going to be a bloody violent action, and there was only a slim chance of success.

But in the end, there was no other option open to Eisenhower, so he made the decision to order the attack.

The same way Pickett sent his men down that hill toward the Northern lines.

In the end, the outcome of both battles was the better one for humanity. The oppressor lost.

The failure of Pickett’s charge was the end for the South. They withdrew on the Fourth of July, and essentially remained on the run back to Virginia, where they were ultimately forced to surrender in 1865.

The Confederate States of America ceased to be a nation, and was subject to re-admission to the United States of America. As a consequence, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, made in January 1863 before Gettysburg, served as the impetus for the 13th Amendment which actually abolished the slave trade in the U.S.

That’s the short version we got in grade school. Over the years I have learned about martial law being declared in New York City to put down draft riots, the fact that the Emancipation Proclamation only applied to the states that were no longer under Lincoln’s control, and numerous instances of political compromise and military ambition that may have prolonged the conflict and increased the suffering.

This is not to say that the cause was not just and right. But we are harming our ability to learn from history by oversimplifying it. We encourage the growth of falsehoods that become rallying points for bad ideas. We tend to learn to put things in binary terms. Black and White. Us and Them.

That never ends well.

The period of his presidency is looked back upon as a time of relative order and stability, but beneath the surface the Cold War and the turmoil of the 1960s seethed and bubbled, waiting only for a spark to set it off.

In only a few years the world would come the closest it ever has to an all out nuclear war, and another U. S, President would be assassinated as he drove through the streets of Dallas.

Well behaved cows aside, we are always just one second away from collapse. Physicists say that holding the universe together uses more energy than letting it fall apart. We see the falling apart -entropy- as the arrow of forward time. This is one of the reasons that modern science initially spurned the idea of time travel. It takes more energy to reverse things than there is in the universe, so you can never go back.

However, “back” and “forward” are potentially the limitations of our perception, much like our inability to see wavelengths of light in the infrared and ultraviolet with our poorly evolved meatsuit eyes. Everything exists in the now, but our wee brains can’t take it all in. We have developed a kind of psychosis to shield us from the incomprehensible everpresent, and that is this notion of unidirectional linear time.

Which is why I prefer to time travel. I hope that this little trip has been entertaining to you. I understand it may be a bit heavier fare than you expected, but we are descending down into that Winter Dark, when thoughts of death and doom are closer to the surface, and it is never a bad thing to remember how close we are to the footsteps of chaos.

The American Civil War did not begin with the attack on Fort Sumter. It did not begin with the election of Lincoln, or numerous political appeasements from the beginning of the 19th Century. In some sense the Civil War began with the inclusion of institutionalized slavery in the Constitution. But it is our own long history of barbarity that fuels it, and that has sadly not been resolved.

As I have traveled across the country in the last few months I have seen and heard much to indicate that we are by no means safe from repeating the mistakes of the Confederacy or the Third Reich, or the myriad tyrannies and oppressions that mark our human history. The path forward is never straight, and sometimes it goes through dark territory. Choosing to ignore that creates a certainty that we will stumble upon it.

Back next week.