Let the bells ring out, it’s Halloween month again!

I am fairly sure my readers feel the same jubilation when October rolls around (unless I have an audience south of the Equator, in which case, insert “Beltane month”). Some of us sniff that scent in the air as August draws to a close, even though here in coastal Texas “fall” is relegated to a state of mind for the most part.

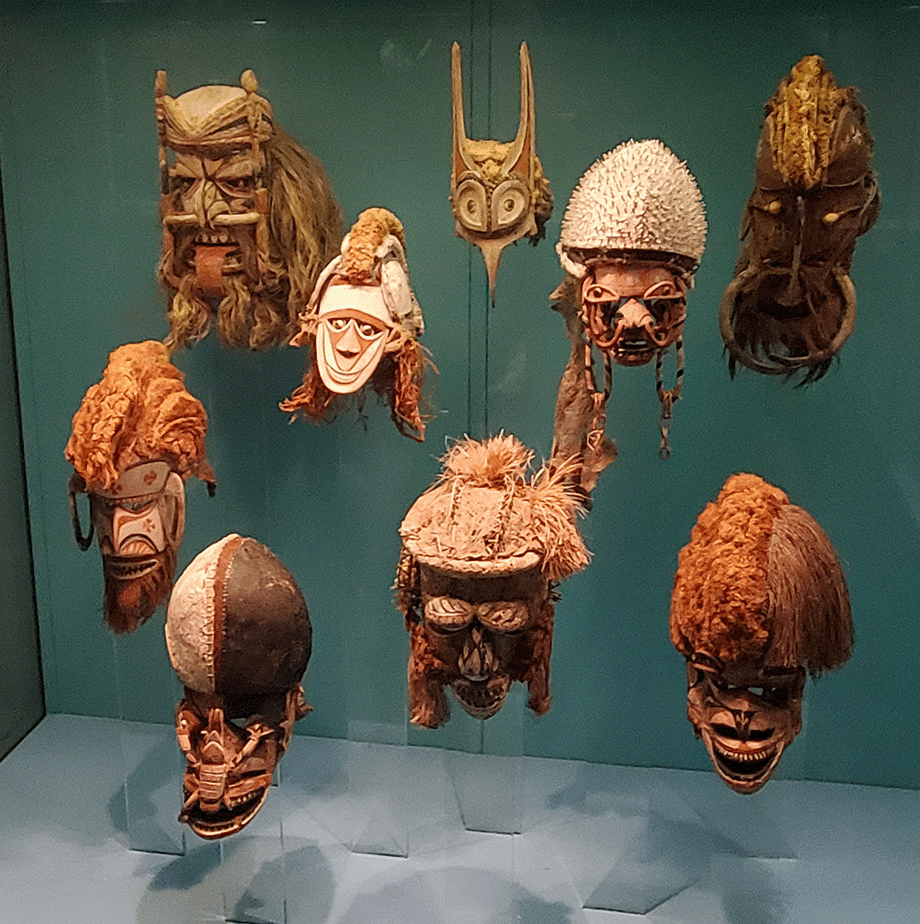

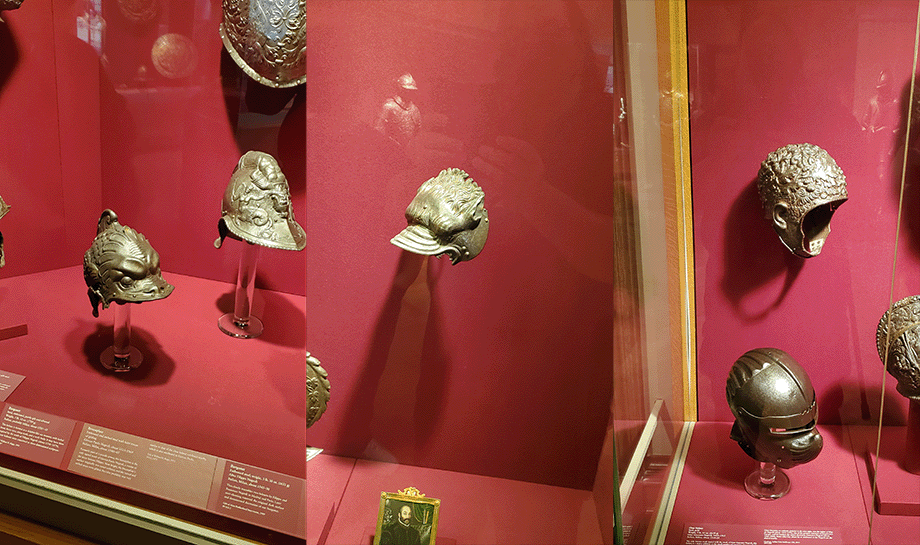

It seems an apropos time to discuss the concept of the mask. I am a collector of masks (I’m a collector of a lot of things, books, guitars, swords, cats, skulls…). I have been fascinated by them since I was a child, through my years working in theatre and film, and as an intriguing part of popular culture. And of course, the ritual and magical use of the mask easily commands my attention.

Que tous les masques que vous portez soient les vôtres

I know I promised at the end of last week’s article to stop referring to the root words of things. Technically this is a direct translation, but our word mask is “larva” in Latin. I find this extraordinary. We can see of course why this term is used to apply to the untransformed infant stage of insects. The larva “masks” the true creature it becomes. But so too, can donning a mask be a transformative experience. When we mask ourselves, we are becoming something else.

This goes way way back to pre-history. We find evidence in the Sorceror of Tres Freres. Underneath his deerskin and horns he is becoming the Spirit of the animal. Whether he is personifying the deity locally for his tribe, or using this to hide himself as he travels the unseen world, we may never know.

Yet there are tribal communities extant who use masked rituals for similar purposes, as well as to illustrate tribal history and legend. In many cases ritually re-enacting a story from myth is a kind of spellwork. In performing the ritual, the acts that brought about the desired ends are reintroduced into the universe, hopefully to remind the forgetful skies to bring rain, or the bored earth to make the fields green.

The ritual use of masks are not relegated to tribal cultures alone, though. Masks, and by extension costume, are integral to much ceremonial magic. And even when we are not garbed in robes the color of darkest midnight, we frequently use metaphorical masks in our work. We take on the role of a particular spirit, deity, or even abstract concept, when performing ritual and spellwork, as surely as that ancient sorcerer donned his deer skin.

In many witchcraft practices these roles are binary and gender-specific, deriving in some cases from more ancient fertility rites. This inbuilt duality is becoming problematic as we welcome into the larger occult community persons who do not fit easily within this paradigm. It’s time to understand that these restrictions are, in fact, just masks to express concepts that are not absolutes, but aspects of the Divine.

It is ridiculous to believe that LGBTQ+ persons did not practice witchcraft in elder times, or that their involvement in the craft did not form a vital part of their personal identity as much as it does for heterosexuals and cisgender individuals. Human sexuality has always been complex, variable, and fluid, depending on culture, time, and belief. It is only one component of that enigma we call human identity, which is still barely understood by modern psychological disciplines, and a total mystery to empirical science.

I’m talking here about the thing that drives around our meat suits, which are as much of a mask as anything you’ll find down at Party City this time of year. The physical body, though we may enjoy it while we occupy it, is not really what we are. We are made of rarer stuff. Stuff that is capable of assuming a number of different forms, playing a lot of different parts, and experiencing the greater Divine nature in a myriad of ways.

We are spirits in a material world.

The mummy mask was sometimes an alternative to the elaborate carved and painted coffins, which some could not afford. The deluxe model belonged to Tutankhamen, and was made from pure gold, and precious stones. This one is only gold leaf over a substance called cartonnage by archaeologists. Essentially it’s papier-maché. Others were merely painted, some even painted directly on the wrappings. When the Roman settlers embraced the trend to mummification, they shifted to beautiful encaustic portraits (a painting medium using pigment, oil, and beeswax) on panels that were bound in the outer layer of wrappings.

Even in death, the ritual mask still has a purpose. In this case, it identifies what our meat suit looked like before time, desiccation, and decay took it away.

Certain Buddhist and Hindu teachings put forth that even that material world is an illusion. Our experience is happening in our minds, and our minds are ineffable, infinite, and eternal.

But as spirits we do enjoy wearing masks from time to time. They make it easier to go shopping for decorations down at the Spirit Halloween store. And to have conversations with other mask-wearing spirits about the nature of human identity, the cosmos, and our role in it.

It’s easy for us to confuse the mask for the wearer. Our minds are fertile places that concoct all manner of fantasies to keep us entertained when we should be paying attention in math class. We see the mask and infer, and elaborate, and imagine, and by the time we actually encounter the other person we probably have them dead wrong. When get to meet the wearer, if we are ever that lucky, it can be a shattering experience.

We must cultivate the practice of seeing through the mask, to those little bits of the wearer that come through the eyeholes and around the edges. While we may still be wrong when the masks come off at midnight, maybe we won’t be tragically so.

It’s also very important to remember that our own masks are on, and that impacts our own perception. I think we’ve all had the experience of wearing that mask where the eyes aren’t quite in the right place, or the mouth doesn’t match up. The bodies we wear and the baggage that we carry in the form of cultural roles and other outward expressions of identity can restrict and color our view of the world we are in. It’s vitally important that our masks fit us properly. Otherwise, we are stifled and miserable and angry all the time.

Remember that the spirits and deities and such that some of us work with are also wearing masks. They may need to go shopping down at the Spirit Halloween store, too. Very often they wear a mask so we can understand and interact with them.

Consider it a kind of metaphysical social media. We interact with the equivalent of a text message with a profile pic, and see the occasional meme post. The actual being we are communicating with may bear little resemblance to what we think they are. Meeting them “irl” could be devastating, disappointing, or ecstatic. But like social media, they may live far away and the chances of that happening are slim to none.

Our meat suits are not up to the challenge of such an encounter anyway. The grimoires are replete with entreaties to “appear in a form pleasant to the eye”. Otherworldly beings exist in forms and fashions that are not that same as the world we inhabit. To come into our space-time, necessitates a “container” that responds to our laws of physics. But that doesn’t mean it’s comfortable or pleasing to experience.

Mohammed was required to look only upon the angel Gabriel after he had passed by, because to see the full countenance would cause him to drop down dead. It’s safe to assume that we are only in the presence of a small portion or aspect of beings of this nature.

On the other hand, mythology and lore has many examples of spirits that live in a single tree, or protect a stream or river. These genius loci are more on our human scale, at least when that scale is limited by the meat suit.

Of course, these creatures could be as the mycelium of the mushroom. They are a greater whole, of which only a part is visible (and even they may not be fully aware of it).

This is not an uncommon concept. There are many versions of the cosmic Divine that suggest all our personal identities are merely a piece of this greater continuum, and that our moments incarnate in the meat suit provide a convenient situation for the self knowledge of that Divine. In which case, all the variations and viewpoints of everyone and everything are just masks that the Divine wears to know about itself. It is an exploration of wonder on an unimaginable scale, and so encounters with any and all should be welcomed, and cherished for what they are.

We are more than just the masks we wear. We wear a lot of masks. Don’t confuse the mask for the wearer. Especially when the wearer is you.

May all the masks you wear be your own.

Thank you for the taking the time to read this. It’s my busy season, so some of these may be shorter than the usual. I’m sure the tl;dr folks among you will appreciate that. I’ll be back next week.

Featured image and Instagram/Facebook/Twitter attachments are cropped from Fritz Lang’s 1927 masterpiece Metropolis. In the frame the Great Machine that powers the city and exhausts the workers is transformed into the demon Molloch, who consumes them into his fiery insides. Another lovely occult reference in this film, and evidence that even a machine can wear a mask on occasion.