So yesterday was another birthday. I am now officially in my late 50s. While that is hardly old, I think it is, with a few exceptions, at least a decade on from most of my readership.

And that’s okay. I don’t build relationships around age. I build relationships around personalities. If you are interesting, and I like you, then I will make an effort to get to know you, regardless of your age or other physical factors. These are, after all, transitory, and probably illusional anyway.

My physical manifestation has been experiencing linear time for almost three score years. My mind goes further back. Way back. Back well before back. infinitely back if I squint hard enough.

And so, I believe, does everyone else’s, though most get hung up on that linear time, physicality, and other limitations. Letting go is difficult. Letting go is scary. Because, there is a very real danger that once you make that trip, you won’t ever come back.

Entering an altered state of consciousness that transcends time and space effectively dissolves one’s physicality.

Our attachment to the meat suit means it is very very difficult to reach a point where we aren’t wondering if the meat suit is sitting somewhere, in a quasi-vegetative state, slowly ceasing to function, to the horror and sorrow of all the other meat suits who were also attached to it.

There are, in fact, accounts of monks and hermits in many faiths to whom this actually happened. Their spirits roamed beyond the limitations of the world around them, but their physical bodies starved to death.

Which of course brings about the question as to whether or not the freedom of the spirit was the necessary death of the physical host. Is the dissolution of the physical experienced by the total awareness of the spiritual ultimately only possible by breaking that bond and letting the physical cease to function?

And if the limitations of the physical are only illusions, then why does it matter? Why do we worry about what happens to that meat suit?

And why do we put up with the aches and pains and longings and hungers and frustrations and limitations of the meat suit as it starts to wear out? Each day I feel more and more the weight of the years on this physical form, so why, if we know that the ultimate expression of self is in a dissolved spirit where all are one and one are all, do we continue to return to the burden of physicality and temporality?

Life is a constant mystery.

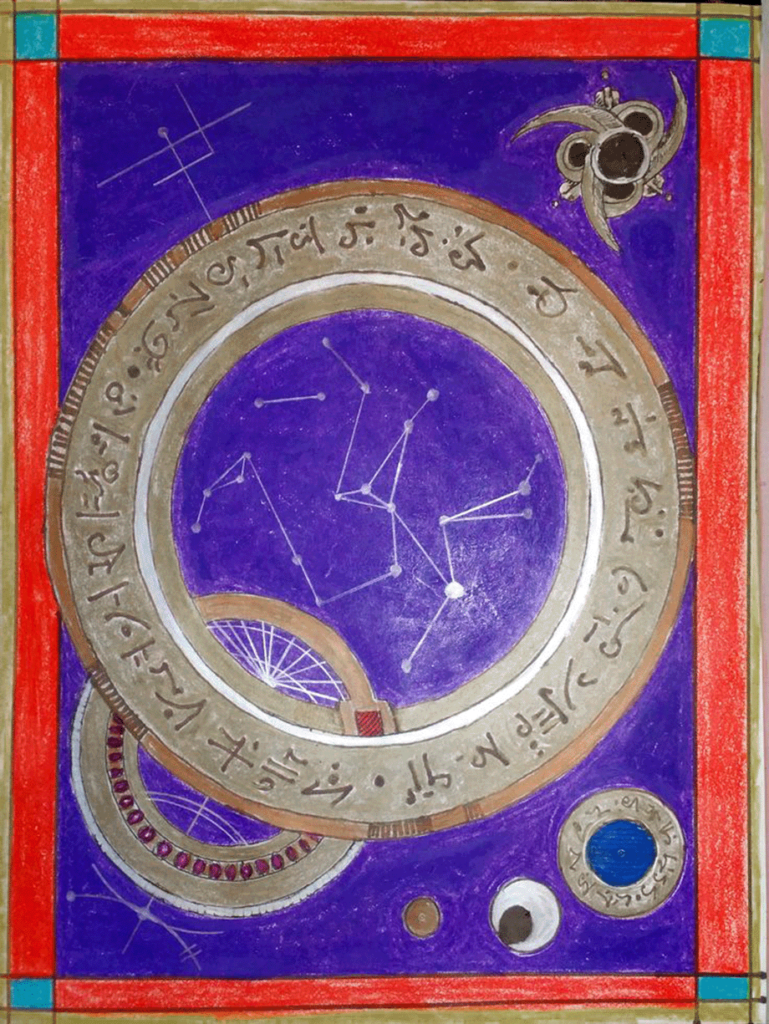

The middle image is of a modern orrery. An orrery is the forerunner of the planetarium, and is a cunning clockwork device that simulates the relative motion of the earth and moon, and sometimes other planets, around the sun. Orreries came about after Copernicus succeeded in replacing Ptolemy’s earth-centered universe with a sun-centered system, although astrologers continued to use the geo-centric model, and still do today, when calculating aspects and planetary influences.

The instrument on the right is a more or less modern device called a sextant. This is because the curved piece on the bottom represents 60 degrees of arc (30 degrees to each side of the center position). A similar instrument called a quadrant represented an arc of 90 degrees, but as it offered no great advantage in navigations, the larger size was quickly dropped for the improved model. The principles of the sextant derive from the more ancient astrolabe, but essentially involve calculating one’s position in space by using the angle of sun or a star at a certain time of day. The sextant can also be used horizontally to measure angles between points in the distance, and through the use of trigonometry, calculate range to one of the points.

The accuracy of these antique analog instruments varied by manufacturer and user, but a quality device in the hands of an experienced user would be comparable to a modern GPS locator, at least for purposes of general navigation.

Even in those moments when I can take my mind way back before way back before before, there is still some mystery to work out.

We are responsible to ourselves, to the nature of life itself, to keep poking at that mystery.

We should never take anything at face value. We should always wonder. We should always question. We should always wonder if the reality that we are experiencing is the final and ultimate one. Because if one is an illusion, then there is always and ever the possibility that all are.

I have been something of a cynic since childhood. A cynic is different than a skeptic. The skeptic says, “I don’t necessarily believe this, but if you have proof, I am open to changing my mind.” A cynic says, “I don’t necessarily believe this, and I need to see the proof of your proof. Which I also may not believe.”

If I look up the definition of cynic on the various web resources, it’s been boiled down to a general distrust of people’s motives and/or a school of Greek philosophy that was based on the rejection of convention or societal norms in favor of harmony with the cosmos. I’m not entirely sure I agree with either definition, which, of course, is the cynical point of view.

Of course, if you dig into it, skepticism is also a philosophical concept, based on the idea that we cannot know some things.

So for the skeptic, “It’s a mystery.” is sufficient explanation.

For the cynic “But is it a mystery?” is the more apt question. Why do we accept this is an answer? Is it impossible to know the answer? If I say I do know the answer, should I be believed?

I have spent the majority of my life in pursuit of wisdom, knowledge, and insight. Yet for every guru or teacher or prophet or messiah or philosopher or iconoclast, I am always asking “but what if you’re wrong?”

Because I am always asking myself that question.

“What if you’re wrong?”

This is not the same as the apostate or heretic, who doubts their resolve against the dogma of their former faith. It is not the fear of those who, upon hearing the soft tread of the psychopomp approaching, strive to find some peace of mind in the shadow of impending demise.

It is a simple, semi-scientific, quest for error.

I bought off on scientific method early on. It appealed to my sense of logic and reason. I’m not sure it even gets taught in the schools today, so I’ll cover it briefly here.

Theorize. Test the theory. Observe the results. Refine the theory. Repeat as necessary.

Theorize is that part where we all go “this is the way things are”.

Test the theory is that part where some go “but is this the way things are?”.

Observe the results is something like “no, this is not the way things are”.

And finally we come to “Oh, so this is how things are”.

But life is a constant mystery. We have to keep running the loop. We must repeat as necessary. And it is always necessary.

A sculpture represents a specific moment. That is, it has the dimensions of up-down/left-right/ and forward-back, but within itself there is no past-future. It is a fixed point in time, that occupies space. Ironically, because all sculptures as we experience them exist in that four dimensional space-time, it is a representation of a fixed point in time that is moving through time.

Two-dimensional images abstract this even further. They represent our mental experience of four dimensions frozen at one point, and then flattened out. They no longer contain the dimensions of forward-back and past-future, but our minds are able to accept this because we innately learn how to abstract four dimensions to two as our brains grow. We have a further complexity in that we are able to perceive two dimensional images that contain representations of three dimensions (see below) and two-dimensional images that represent two dimensions. This was a conundrum explored by the Cubist and Surrealist movements in art, and ultimately gave rise to non-representational art in the mid-twentieth century.

Yet the history of visual and plastic arts gives us a number of examples of intentional manipulation of our perception of space time. If one looks at the conventions of Ancient Egyptian art, we are confronted with figures who have heads, hands, and legs and feet in profile, but torsos and hips portrayed frontally. It’s clear, however, from their sculpture work that they not only understood, but mastered depictions of three-dimensions. The deliberate choice to create such distorted flat images in two-dimensions derived from their concepts of the nature of things. They had to include, as much as possible, a clear picture in two dimensions, of the three-dimensional form, otherwise the gods and spirits might not recognize it, and the magic would fail to work.

Science and spirituality would both have you believe that they are mutually exclusive disciplines, but this is an erroneous idea. To paraphrase from Pauley Perrette’s character on NCIS “I believe in magic, prayer and logic equally”. Arthur C. Clarke, who was both a famous science fiction author and inventor of the geosynchronous satellite, gives us “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. And for me, the one thing that I think both science and spiritualism should have in common is that desire to always question the status quo.

Time and space have changed significantly since I was a child. Our understanding of modern physics today embraces concepts that were considered in the realm of science fiction when I was growing up. This is because the more we learn about the nature of the observable physical universe, the more we are forced to alter the accepted viewpoint, and in some cases, to admit an as-yet-unknown nature which is not quantifiable using the current means.

Isaac Newton had to invent calculus in order to express his understanding of the nature of space and time. Modern physicists have expanded on his work, but we may require another watershed like Principia Mathematica or the General and Special Theory of Relativity to leap past our present limits.

Most people work their way through the world without an awareness of even the basics of Newtonian physics, to say nothing of the implications of quantum uncertainty and the potential of multiple universes with alternate timelines. Gravity is a literal fact. It does what it does, and keeps us all from sliding off into space, and that’s a good thing.

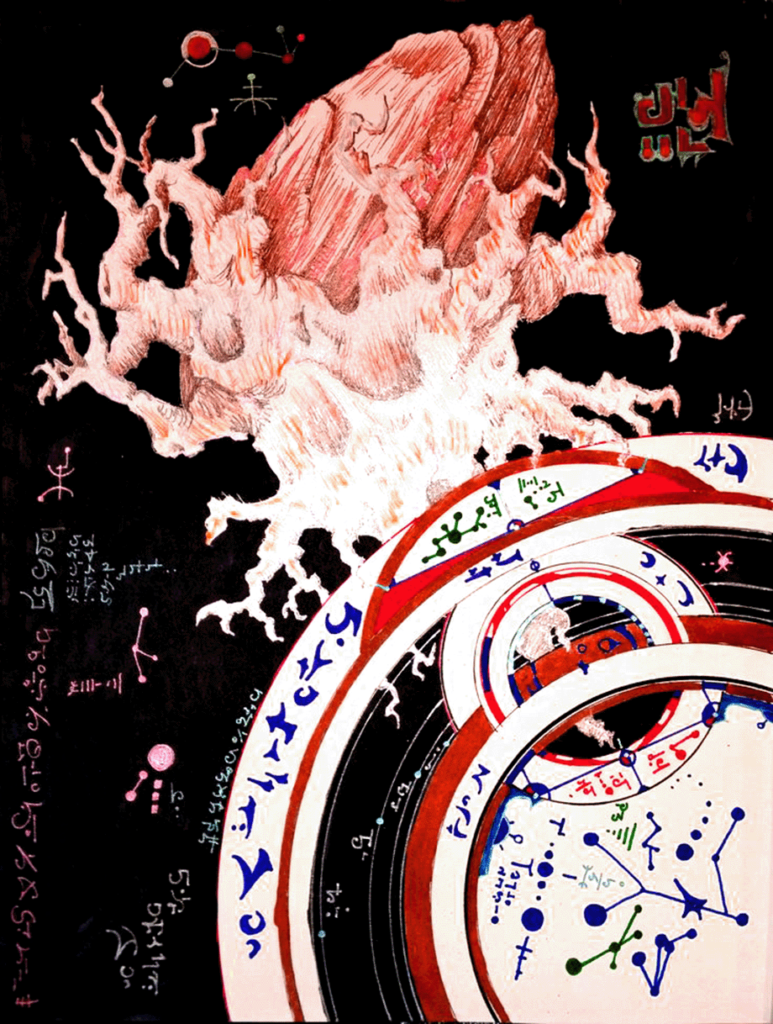

Yet the complex interaction of gravitational forces alone that make possible our habitation of this little rock are staggering to ponder. We are all of us pulled toward the center of the Earth. Yet we are also pulled toward the Moon as it slowly circles the earth overhead. Both Earth and Moon are drawn inward toward a massive star we call the Sun. It is only the speed at which we travel around it, and occasional tugs from other planets in orbit, the smaller one’s due to their distance, and the larger ones due to their size, that keeps us from spiraling in and melting.

Our meat suits have evolved to live in this soup of interlocking forces that move the universe on a cosmic scale. The invisible engine of gravity moves the stars in the heavens, and causes them to be born and to die. It whirls the galaxies together, in orbits around great dark objects of such unbelievable size that space is curved toward the infinite, and light itself cannot escape. It is a truly amazing and terrifying cosmos we inhabit.

Before Mr. Newton and the Enlightenment, the operation of this system was bound by the works of Claudius Ptolemy, a researcher and encyclopedist at the library of Alexandria in the first century AD.

His Four Books provides the basis for Western astrology, and his Mathematic Systems was the astronomical text that taught how to plot the movements of the stars. Like Newton, he wrote the math text to explain the apparent motion of the heavens. Unlike his latter day counterpart, though, his interest in that motion was for the use of astrological horoscopy.

Astrology, and most likely the mathematical models necessary to support it, was practiced as a science by the ancient Chaldeans, and probably older civilizations. There are increasing numbers of discoveries that stone-age peoples were observing and possibly recording the passage of time using the positions of celestial objects around the world.

Stonehenge is probably the most famous such site, but there are a number in the Americas, and recently many more have been found in Asia and Africa, so there is some reason to believe that humans marked time and specifically events like the solstices and the equinoxes at a very early point in our development, and that we used similar methods regardless of geography.

We might expect that the reason is simply agricultural. When one is dependent upon the crops, one should probably know when to plant and when to harvest, and a solar observatory is a more accurate means of working out that information than a tally stick or other similar counting mechanism.

Yet these constructions, some of which obviously required a lot of people and sometimes centuries to build, seem a bit over the top for this purpose alone.

Evidence supports that Stonehenge actually began as a wood-henge (and Woodhenge is also a nearby site) that was modified repeatedly over a span of several hundred years. So a simpler, and certainly easier to build version was sufficient. We can speculate that stones were later involved, because they would be more permanent and lower maintenance.

But that only explains the small stone circle, at least as far as practical function is concerned.

To harness the labor and skills necessary to bring the great big stones that make up the final stage, you really have to be looking at more than just keep track of time for the harvest. Recent discoveries at Stonehenge, and at places like Gobekli Tepe in Turkey, suggest that perhaps it was the other way around.

Both sites appear to have been places where large groups of more or less nomadic stone-age tribes would gather at specific times, and have large festivals. Theoretically such festivals included a lot of eating and drinking, and logically might also involve trading, cultural exchange, marriages and betrothals, etc. before the crowd sobered up and went back to their usual ranges.

The desire to support these occasional meetings may have led to increased domestication of both animals and plants, in order to meet the demand for annual or semi-annual feasts.

As we now know these supposedly “primitive” people were gathering at pre-appointed times, we have to consider that they had a fairly good command of both time and space outside of the calendrical functions of the solar sites themselves.

That is, a tribe needed to know how many days (or thereabouts) it would take for them to travel from their usual stomping grounds to the ceremonial center. They then would need to be able to subtract those days from the date of the meeting, say, the Summer Solstice, in order to know when to leave so they could be there on time.

While it’s hardly rocket science, it does mean that at least some members of the tribe both had the necessary information, and could keep track of the passage of days, without the need of a Stonehenge type calendar. While one might argue that the numerous other stone circles and semi-circles around the world were local “clocks” there’s a bit of problem.

Solar calendars like Stonehenge are “set” according to equinoxes and solstices. If your travel time from the local clock, in say, Northern Scotland, to Stonehenge, takes about three months, then you can leave on the equinox and arrive on the solstice and reasonably expect to get back on the next equinox. But, aside from the issues this brings up with planting, harvesting, etc. in a fixed agrarian society, it’s also just not right.

According to internet mapping software, one can walk from Inverness to Stonehenge in around 8 days. Now presuming one is not actually constantly walking, and is possibly also bringing along slower moving livestock, a more reasonable journey is probably about a fortnight. So one would need to know about two to three weeks before the Summer Solstice that they needed to pack up and head south.

On the other hand, we might look at the equinox to solstice ratio as indicative of seasonal migration, where both people and animals left the colder northern climate for a more favorable winter on the Salisbury plain, and returning to the fields in Scotland just about the time the spring grazing was beginning.

So many of the ancient magical dates revolve around the agricultural imperative that it’s impossible to say which came first, the farm or the festival? But if people are migrating to festivals rather than fields, then we have to admit the possibility of early calendar devices being accessible to stone-age peoples without being locations in a landscape.

Tools similar to quadrants are known to have existed in Ancient Mesopotamia. The exact date of their invention is unknown. These devices are designed to work out the position of the stars above the horizon, and thus can be used to calculate both location and time of the day as well as the day of the year.

Prior to the global positioning system, a variation of this technology, the sextant, was used for the same purpose.

In the Middle Ages a very complex version called an astrolabe was probably developed in China, and made it’s way westward along the Silk Road, which the development of the astrolabe made possible. In later times, as the Muslim culture spread out across northern Africa, this amazing device took on more significance in that it could be used to determine the location of Mecca and calculate the proper times to stop for prayer.

Astrolabes, quadrants, and sextants all operate on measuring the angles of the sun or other fixed celestial point, in relation to an horizon. The astrolabe uses a full circle, while a quadrant and sextant use a fourth and a sixth, or 90 and 60 degrees of arc, respectively. The accuracy of these analog devices when used by a skilled technician is comparable to computers and GPS systems. Manned space craft in Earth’s orbit still carry a sextant.

I obviously have a fascination with the mechanics of the planets and stars. In a quantum multiverse, where nothing is ever in the same place at the same time ever, it seems to me difficult to casually dismiss that unique moment into which we are all born as an irrelevance.

As we draw near to, and enter into our birth date, even though it is not the same as it was when were were born, the nearer factors, that gravity of the Earth, Moon, Sun, and planets, swirls similarly around us. All our local planets inhabit the gravity well of the Sun, so it is not surprising that our Solar Return augurs importantly. Our Moon signs, though the Moon is smaller even than the Earth, derive from a much closer relationship with her forces. The meat suits evolved to have about the same amount of water in them as the Earth does on it, so the effects of the Moon on tides cannot easily be dismissed.

Astrology, astronomy, and the human need to quantify time and space are as ancient as our brains. If we limit ourselves to the scientific only, and suggest that the spirit is a quirk of evolutionary mutation, present only between the fertilization of the gamete and the end of respiration, we are still faced with the question of how that consciousness comes to be, and what it’s purpose is, because it simply can’t be explained as an adaptation to environmental survival. Self-awareness might argue somewhat of an advantage. Language and the ability to pass on information, certainly is a powerful survival factor. But the bees have that and they’re not doing so well.

It’s fascinating to think, though, that the bee language, and the information system that affords them an evolutionary advantage, appears to be related to navigating based on the position of the Sun. So our own connection to space and time may be as integral. We may be drawn to the sky because somewhere back in our evolution, we had a built-in orientation to the positions of the celestial objects.

Ignoring that because “astrology is a pseudoscience” is not to our advantage in our journey of self-discovery as a species.

As always, I question everything. I recommend it as a way of living. It can take a lot of time and energy, but you may find it worth the extra effort.

I’ll return next week, after few more days around the Sun.