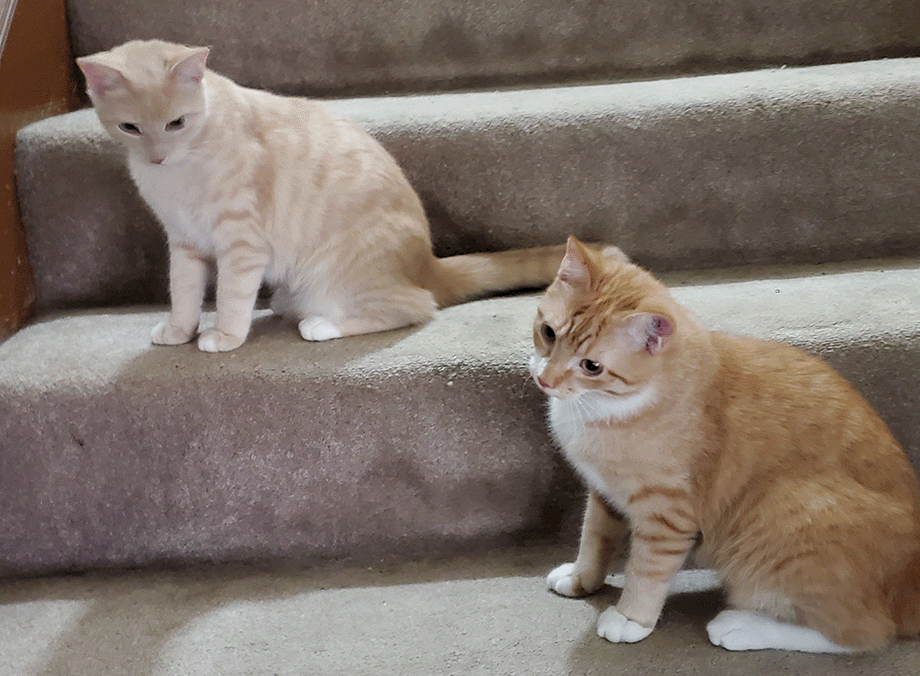

Last September, my Good Lady Wife added two foundling kittens to our pride of house lions. They were lately born when she discovered them, but now they are old enough to be integrated with the rest (two of which are elderly) on a more or less permanent basis.

There’s an old adage about the curiosity of cats, and the potential outcome of same. So we spend a good deal of time telling them to get down, get off that, don’t bite that, etc. In the hope that eventually they’ll either learn it’s not safe, or simply tire of being yelled at about it.

The little princess though, has decided that I am her people, and that she must at all times accompany me in whatever I do. This includes, according to her anyway, my time in the studio. I have explained to her why this is a bad idea, using exactly the words of the title, but she seems unconvinced as to my sincerity, and remains intent on exploring the obvious cave of wonders I am keeping hidden behind that door.

There is indeed fire. In addition to two actual high-temperature torches, there are several soldering irons, at least a pair of wood burners, and at any given moment there will be incense and/or candles burning.

As to acid I keep several kinds. Some for metal work, some for printmaking, and some for the odd mad scientist experiment and/or old school film photography.

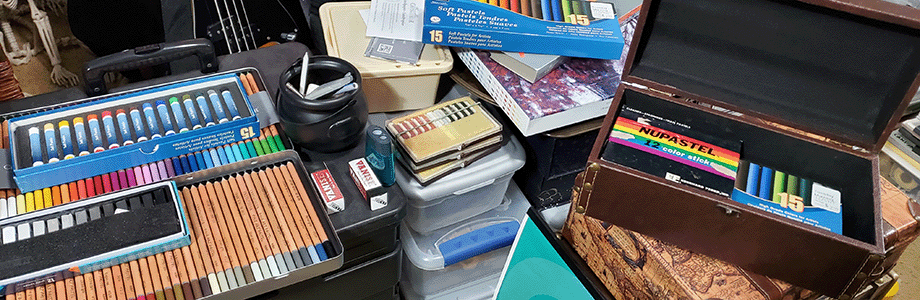

And under the heading of poison, I have quite a selection. There are alcohols, acetones, ammonias, caustics, coal tars, cements, latexes, polymers, binders, adhesives, pigments, dyes, and inks, not counting things that come premade that most people would recognize as paints. I even have the alchemical standbys of several small vials of quicksilver and a large golden hunk of pure brimstone. ( and never you mind what for).

There’s various powders that are bad for the lungs and/or toxic if not deadly when improperly handled. A large number of the containers are marked with “Highly Flammable” and “Use With Adequate Ventilation” and a few that require protective gear.

And on top of that are the other “odd” things which may include crystals and oils and “organic materials” that should only be rarely touched and never tasted.

So in short everything that would delight and entice a curious kitten into a grand but all too brief adventure. Hence the door to the studio stays closed.

I have started to think more and more about the quantities of very bad things that I have amassed in the name of art. And aside from a few things that are just “vibe” in the space, the majority of this collection is for the making of art of various sorts. In my career as an artist I have thankfully seen a shift into less toxic, less carcinogenic, and more environmentally and even vegan friendly materials. But in some cases there’s just no substitute for the bottle of danger ketchup.

I am now old enough to be sensible regarding handling these materials. When I was in my twenties in art school, I would routinely eat, drink, and smoke in front of the easel. As with many artists, the paintbrush was conveniently held in my mouth when both hands were needed. There is no doubt I ingested paint that included some dangerous heavy metals, and toxic pigments. To the extent that I absorbed enough of this to do permanent harm is anyone’s guess. I don’t have the symptoms of heavy metal poisoning that may have been responsible for some of Van Gogh’s insanity (or at least exacerbated it). But then it’s hard to say whether my present weirdness is some lasting legacy of eating cadmium and snorting turpentine in the early 1980s. Among other things.

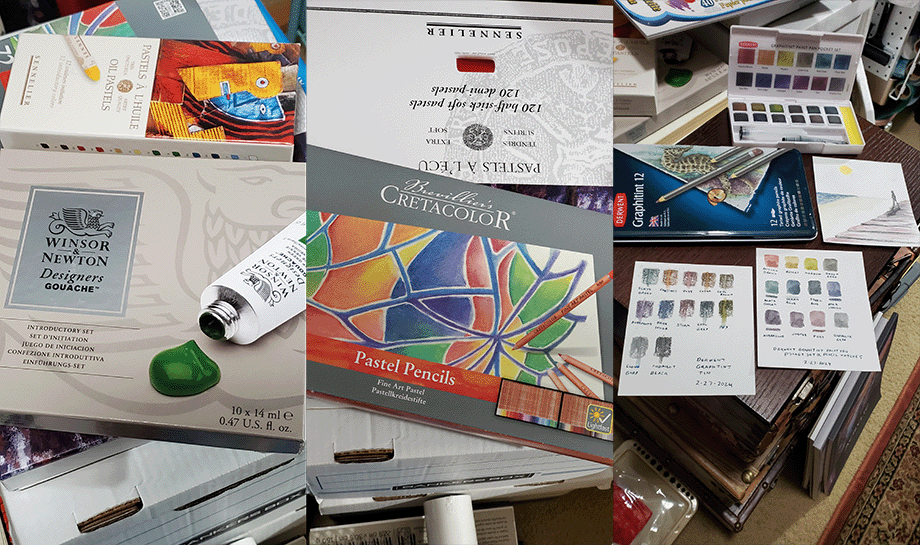

Part of this new awareness has been a deep dive into the formulation of various artistic materials, as well as into their history. I am looking to find means of producing works of longevity, while at the same time minimizing exposure to material that may decrease my own.

At basis, most art materials consist of two or three components. The first is pigment, the thing that actually makes the color. Next is the binder, what causes the pigment to stick to the paper, canvas, panel, wall, or boulder. Finally, for some there is a solvent or diluent, that makes it possible to mix the binder and pigment into a form that can be easily applied, but which will later on be permanent.

Depending on your pigment, there may be some toxicity issues. Natural “earths”, organic plant pigments, and synthetic industrial colorants can contain chemicals that are inimical to the meat suit. The cadmium and cobalt colors are becoming harder to get and then only at a premium. This reflects as much the rarity of the compound as it does the environmental hazards in handling and preparing them.

Binders, on the other hand, seem less of a problem, unless you are allergic to latex. Synthetic polymers are being substituted for natural gums and resins, and beeswax is being eschewed to make vegan friendly materials. The downside, though, is that synthetics are inevitably petroleum distillates or by-products of the petrochemical industries. As such they carry along the same downsides as any fossil fuel: environmental pollution and resource depletion.

The solvents are frequently the most dangerous part of the mix. The oldest of these is probably turpentine, made by distillation of pine resins. In combination with certain other plant and nut oils, this chemical makes a painting medium that allows dry pigments and powdered resin binders to be spread by a brush, and to achieve a hard cure. “Mineral spirits” another euphemism for petroleum distillates, is a more modern second, and then special preparations like alcohol and acetone round out the gamut. Because they are designed to break down or at least liquify the organic matter of the binder, and then to cure by oxidation or evaporation, the volatile organic compounds given off by these solvents are a big problem in the artist’s studio as well as the general environment.

Forty years ago, the detail of this wasn’t part of a general art education. There were vent hoods over the acid vats, and crossed bones over the poisonous cocktails, and in some spaces no smoking signs, but getting deeply into both the chemistry and operation of what made a paint was not part of the curriculum unless you were taking a special course in grad school (or were a chemistry major looking to score a job with Dow or Dupont).

In fairness, most of the students in my painting classes had little interest in that level of detail, and I probably would not have either, except that I was always trying to paint on things that weren’t meant to be painted on. This encouraged a broader understanding of the various compounds available, but no necessarily the awareness of what they were made from, or how they worked. Over the years a large number of these compounds have left the market, because they were toxic. An example of this is the so-called “magic marker”

This term is frequently applied to any sort of felt tipped ink pen used for drawing or coloring. But the original trademark was a clunky combination of a metal ink cannister and screw on cap with the felt wick. These were developed about mid-century and aimed initially at illustrators and layout artists. The Madison Avenue advertising industry used them to produce brightly colored idea studies in rapid fashion.

The chief drawback of these was that the ink solvent was xylene or toluene. While not fully proven carcinogenic, these were linked to birth defects, liver and brain damage, and frequently caused dizziness, headaches, and disorientation. These were the same compounds used in the “airplane glue” the kids of the 70s were huffing to get high. So this should explain a bit about some of the advertising you saw created in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Most felt markers since the 1990s use an alcohol or water base, but the adult coloring craze and the demand for low-cost materials means possible importation from less regulated overseas manufacturers. I have sets of “professional” alcohol markers, and I have “discount” alcohol markers, and while I’m not sure that the cheaper ones are using something as toxic as toluene or xylene, they’re definitely more pungent and powerful in a closed room than the high end ones.

I wonder how many ancient shamans scarred, marred, and potentially ended themselves trying to find the exact combination bear fat, beeswax, bird egg and berry juice would render the perfect bison on that cave wall. I’m sure there had to be a number of disastrous failures before time honored formulae were able to be passed down to the apprentice and the acolyte. Such knowledge was magical and sacred, and conveyed powers which were beyond that of the rest of the tribe.

Throughout our history the connection of art and ritual is constantly reinforced. Art as ornament, until the most modern of times, still carried some sacredness or symbolic cachet. Likewise the making of such art was closely guarded, practiced by specialist like the scribes of Egypt and the masons of the Medieval Gothic. We can analyze and dissect and understand their methods and materials now in a more democratic sense, but in doing so, we have left the sacredness behind.

Most of the artists I went to school with simply wanted to know what combination of A and B was required to get their paint to flow smoothly and dry quickly (or slowly) or be thinner or thicker. The “why” of it was on no interest to them. I see a great deal of this echoed in much of the magical community, looking for a “practical” approach, like a cook book, and speaking of “theory” with the same derisive nostril as a third grader might speak of “math”.

The one without the other certainly is functional. A list of things to get, step by step instructions, and what to do if you catch the curtain on fire, and that’s all. But what if that doesn’t work. What if you prefer pecans instead of walnuts in the brownie? Is it a simple matter just to substitute one for the other?

There are those who would argue that, but I’m not sold on the concept as a universal truth.

There are oil paints. There are water-based paints. There are now some paints that can be mixed with oil or water. But not all of the water-based paints can be used with the oil based paints and vice versa. Luckily, these are labeled relatively clearly down at the art store.

But this is not the same with everything, and not the same with spell work.

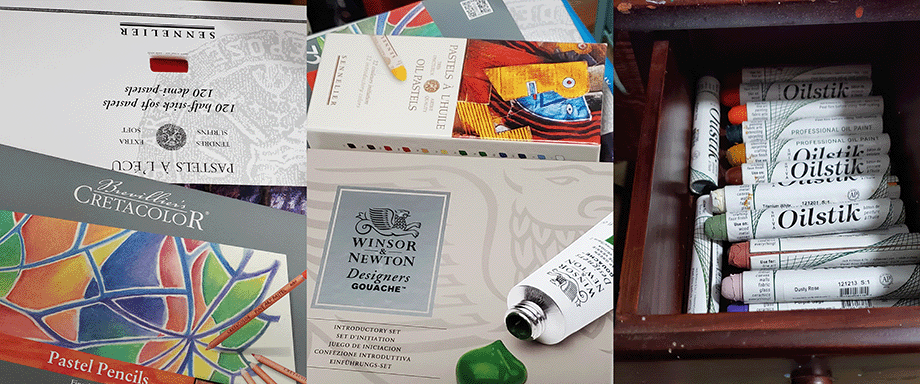

For instance, there is a thing called an oil pastel. Presumably, this is because it was devised to create the same kind of immediacy and painterly approach that chalk pastels were used for, but without the crumbliness and dust. All well and good.

Chalk pastels are made by taking color pigment, fine kaolin clay, and enough binder to get them to stick together and to the paper. As a consequence they are quiet fragile and dusty and require applying a “fixative” of some sort to the finished work to glue it down. Prior to our modern aerosol cans this was done by atomizing a dilution of water and gum arabic or rabbit skin glue onto the work.

So around the turn of the century pigments mixed with wax instead of clay came about, and these were softened with “mineral spirits”. Labeled “oil” pastels because they contained a petroleum based solvent.

Now the natural inclination is to think that oil pastels and oil paints are fully compatible, and that one could use the stubby little crayons as a perfect means of drawing your composition under your painting.

It turns out that this is a really bad idea, because unlike the linseed or walnut oils commonly used for oil paint, the petroleum oil in the pastel never actually “dries”. So the oil pastel oil will dissolve the oil paint oil, or at very least make it tend to slide off the drawing.

This is further confused by the fact that you can use turpentine and oil painting mediums to “paint” with oil pastels and achieve a limited chemical curing that makes them behave more like oil paint and be less subject to surface damage.

Then there’s the oil stick, which is really oil paint in a stick form, not to be confused with oil pastels.

Making these work together harmoniously is a job in itself, and only achievable if one has a really deep understanding of not just the how but the why.

Making them work, and making them archival, so that an art collector or museum can expect the value of the piece will be protected in the long term, is an even more complicated task, with additional layers of chemicals and processes arcane and obtuse.

I view the process of “deep magic” with a similar eye. And I use that term to distinguish from the archaic and elitist notions of “high” and “low” magic. Practical magic, is by definition intended for general purposes to get things done. I use it. I have great respect for it. It works.

But it’s closer to a sketch than an oil painting. And there’s nothing wrong with that. There’s no need to take the time and effort and complicated process of making an oil painting when a sketch will do.

There are a lot of how-to books that take the approach of a cookbook. This is the same for art as it is for spell craft. There are a few that take it to the next level, where there’s a bit more said about the bits and pieces and putting them together. But in the end you probably won’t find a single art book that gives you the how and the why at that level of detail, and you aren’t likely to find a spell book that will either.

At least I haven’t. I’ve had to go put the pieces together from a lot of different places, and I’ve had to grow the knowledge to know when what I find is potentially useful, and when it’s purely selling something.

I hope you have found this rambling potentially useful. It is last minute due to the demands recurring ill weather on the Gulf Coast is imposing from my day job, and thus there are fewer images here than usual.

Perhaps next week we can get back to a better balance. Thank you for reading to the end.