If you’ve been following along, I suppose you’ve noticed a theme going on here. A theme song, in fact. I’m sure you know the words. All the best weirdos do. An appreciation for re-runs of this odd ball 60s sitcom, and the various alternate versions featuring those strange people from the pen of cartoonist Charles Addams is something that runs somewhat commonly through witchy people of my acquaintance. To my mind is a part of the modern “witch aesthetic” that we hear bandied about online. But I’m sure there are some who are oh-so-serious as to debate that assessment.

I’ve written at length about the Addams family before, and am trying not to repeat myself overmuch in this series of articles. Yet the world is cyclic, and ideas come back around. Just like Halloween. That’s actually somewhat comfortable, and really somewhat necessary.

If we as a species could get everything right the first time through, we’d have all attained NIrvana and moved on to whatever challenges await us at that next plateau which is probably not the final state either. Or as surely as the oscillation model of the universe, we are disturbed and distributed out of that state to try and learn again.

Point being, things do repeat, they give us the opportunity to relearn, to renew, to grow and expand, and to re-experience, both good and bad. Re-experience and remembering is an important human activity, because we gear a lot of our lives toward it. We have our favorite foods, our favorite books, our favorite movies and TV shows, and all the assorted knick-knacks that go with them, so that we can treasure them repeatedly. It gives us a fixed point in an ever-evolving cosmos that can be awfully awfully big and awfully awfully indifferent and cruel.

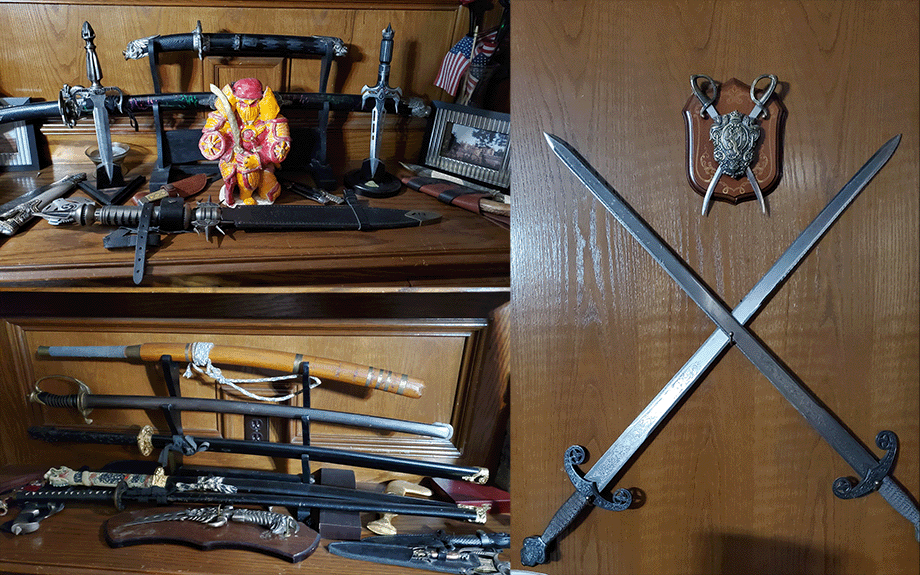

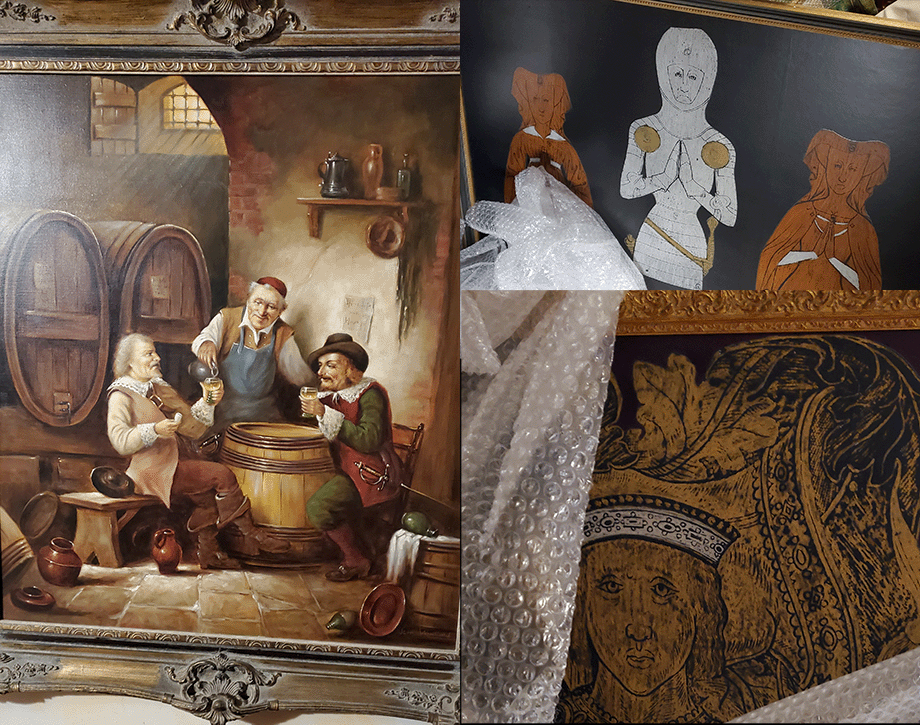

So, yes, my house is a museum of my own life experiences, the things I have liked enough to collect over the years, and the things that I want to keep around me that probably have zero practical purpose.

Like a set of china my great grandmother acquired with S&H Green Stamps back in 40s. For those who have no idea what I am talking about, savings stamps were the precursor to airline miles or credit card cash back. They were typically given out by service stations (what you’d call a gas station now) as a premium when people made a fuel purchase. If you saved enough of them, by pasting them into a booklet they’d give you, then you could purchase items from a catalog provided by the stamp company. In this way, consumers could acquire things for which their ordinary cash flow was insufficient, without needing to qualify for a credit card or payment program, which in the elder days were much harder to get.

The practice of thrift – as it was known – was more fundamental to the middle and working classes in American society until around the 1980s. Saving more than spending was the way of things, because ultimately you’d need to get something that cost a lot, and financing was not something easily accessible to those who really needed it more than the Vanderbilts and Pierpoint Morgans.

It wasn’t just cash, of course, it was all the stuff. In my grandmother’s house were at least five complete bedroom sets, multiple tables, chests, cabinets, sideboards, buffets, sets of dishes, pots, pans, pickling crocks, butter churns, cake stands, and untold numbers of mason jars. Huge steamer trunks, ironically owned by people who had never seen an ocean until late in life, held quilts, blankets, and bedspreads, extra pillows and linens, and a variety of old clothes. There were baby cribs and high chairs. There were old toys and a few books, and a dark floorless attic where one might find the discarded wonders of a bygone age (or a Ouija board everyone swears was never in the house).

These were not collected as ostentation, or any sign of wealth or prestige. They had nothing to do with desire, nor were they a sign of a hoarding malediction. These things had accumulated into this house (and a thousand others like it across mid-century rural America) because they had been saved for the future. Because someday, somebody might need them. There would be children. There would be weddings and new households and grandchildren, and those people would need these things because they would not have them. They’d need them until they got enough S&H Green Stamps of their own to get things, and then they’d pass them on to their children and their grandchildren.

By the time we reached the 1970s, though, it became much easier for an emerging rural middle class to acquire new things. That set of old china became a revered heirloom rather than a practical useful item. It was only used on special occasions when all the family was back together for the holidays. And of course it was never used at the kid’s table, because heaven forbid we might chip one of these quasi-antique plates that, since Granny was no longer with us, had taken on a sacred nature.

So by the time my grandmother passed away, and her children were tasked with parsing out the collections of several human lifetimes, the china came to me, where it sits, sadly, in the top of a cabinet, unused, for fear that it’s age means it contained toxic lead in the glaze. In all likelihood, food will never touch it again.

Meanwhile, my generation has replaced our more disposable mid-century hand-me-downs several times, passed on to our own adult children mismatched sets of melamine and discount store china that survived from our earlier days, and are now faced with the daunting task of a looming inheritance of such things as soup tureens and sideboards that no longer serve our lifestyles or really that of anyone living below the millionaire line.

When my wife and I were younger, we entertained with the finest of plasticware and paper plates. Our peers, there for chips and dips and beer and wine, were content with that, since they did that at their own homes. “Charcuterie” often came on their own plastic presentation trays from the grocery, and being the thrifty sort, we washed those and reused them.

When children came along the inherent need for durability and practicality relegated the china and crystal to the domain of locked display cabinets, and very rare use from time to time. As the children got older more practical but “nicer” pieces were acquired, that suit personal tastes and sensibilities, and are easier and less expensive to replace should a guest have a bit too much wine and tip the glass over.

Now the children have moved out to an apartment, and considerably less space for such things, and their careers and lifestyle choices mean that they may always live in an apartment or condo with limited space and need for soup tureens and sideboards and quasi-antique possibly toxic china that will never be used. Their own personal museums reflect their tastes and time, and so these “old things” no longer live as part of the family, as they really should, and have become part of a memory that we can’t easily let go of.

So while this article may serve to educate the docent who will eventually conduct a tour of my unused kitchen for posterity, it probably seems very far afield from ideas esoteric and occult. I’m coming to that.

Samhain in the Celtic tradition is the end of the year fire festival which closes out the living growing world of the Summer and prepares us all for the coming of the Winter Dark, with its unwelcome reminders of death and privation. It was against such death and privation that my ancestors, and possibly your own accumulated these “useless things” from one generation to the next. They were never really meant to become relics, but they almost always do. They end up being the things of the dead people that we keep around so that we remember those dead people.

I have mentioned in earlier articles and discussions with people online, that I don’t actively practice “veneration of the ancestors”. But I still keep Granny’s gas-station stamp china around. The history of these basically worthless objects, as I have shared it with you here, reminds me of the person that she was, the life that she lived, and the community of others who shared that culture, going back to when they came across the ocean from the poverty of Wales, and Scotland, and Ireland, many with just the clothes on their backs.

This doesn’t even begin to take into account the problems in storing and displaying cursed objects, enchanted amulets, and other such items that museums have to contend with. So far most of the dead things in my collection seem content to remain silent, or at least, to only prank when they are lacking attention.

The day after the Celtic Samhain is celebrated as Dios de Los Muertos by the Latin American culture. The Day of the Dead is an overt veneration of the ancestors and festooned with feasting and music and bright colors and sugar skulls. We get more of it here in Texas than perhaps people do in the center of the country, though the Latin population has been expanding from the border for years. I think about the people pressed at that border now, with only the clothes on their backs, seeking some future they can only imagine. I think of the children and grandchildren that someday may look back to them on the Day of the Dead, and point to a plate or a bowl up on the top shelf of a locked cupboard and tell their stories, and remind themselves of the people that they were.

It is important to participate in these cycles. We none of us get to stick around here forever, and when we go, we don’t come back in that same way ever again. What is left behind, be it memory or relic, is important, not just to us but to the memory of us that it will carry into the future. The old plate speaks for us when we cannot speak for ourselves. That’s why we don’t get rid of them. That’s why we try to hold on.

Eventually the memories will change. My children have dim memories of my grandmothers, not nearly so vivid as the one’s I have of my Granny. And my children will probably not have children of their own, and that is okay too. That means that someday, someone may find a box of old plates at an estate sale, and take them to some new life.

Even if, in the end, they become nameless broken sherds in a trash dump, some future archaeologist may haul them into a museum and say, “look, this is what people in the middle 20th century used to eat on”, and there will still be some memory that we were here at all.

We all of us live in a big house on a little rock in space, and that house is our museum. It is our collective memory and the repository of the remains of every one of us that has ever lived. Time rolls out into the past in an unfathomably long scroll, predating our history, our pre-history, and even our being. It encompasses so many cycles of beings that we only comprehend the briefest bits, the tiny parts that through quirks of nature, have survived as reminders of other orders of beings that have lived before us. The time of the dinosaurs is so long ago, that it is conceivable at least one sentient advanced civilization might have arisen, flourished, and disappeared into dust, without leaving any tangible sign of their existence. It is entirely possible that in that vast ocean of years, a civilization could have arisen to leave the earth, and travel out into the stars, by some method we would not even now be able to understand. It is equally possible that such a race survived on a distant world and that because the time between us and them is so vast, they have evolved beyond anything that they or we would imagine came from this lonely little pebble.

The cycles keep turning. We are not the first to imagine and fear that “the end of time is nigh”. We can look into the recorded history and find this sentiment almost constantly plaguing the currently extant culture. It seems that our individual mortality predisposes us to think in terms of the mortality of culture, civilization, or way of life.

In truth, such things are very fragile. Lines shift on the map. The world I was born into is not the world we live in now, nor will the world I leave behind be the world as it is today. I am not always happy with this fact, but the awareness of it as an absolute is helpful in dealing with that discontentment.

All we may do is plant the seeds for tomorrow, and hope that they take some root. How they grow, and indeed, what they will grow into, is beyond our petty power to manage. If we live true to our natures, then perhaps our memories will be honored by those who come after us.

If not, at least the broken pieces may sit in a display case, and remind others how foolish and selfish we were way back when.

I am returning to my prop work now, and will be back in a week with perhaps lighter fare.

A bit of a housekeeping note. Owing to the changes made at the former Twitter, I have pulled the plug on the automatic update to that website. Since apparently my “interaction” doesn’t satisfy the New World Order’s standards for actually sharing my content, there is no point in continuing to post there. If you were someone who actually looked for the link on that platform, well, I invite you to visit my Instagram or the Facebook page for the reminder, or simply come by here Wednesday’s after 5PM US Central Time.