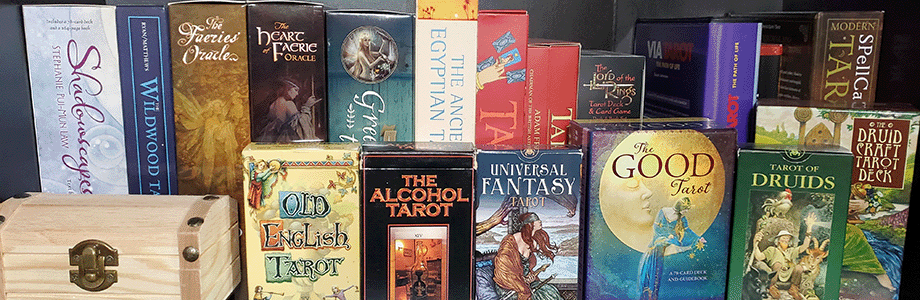

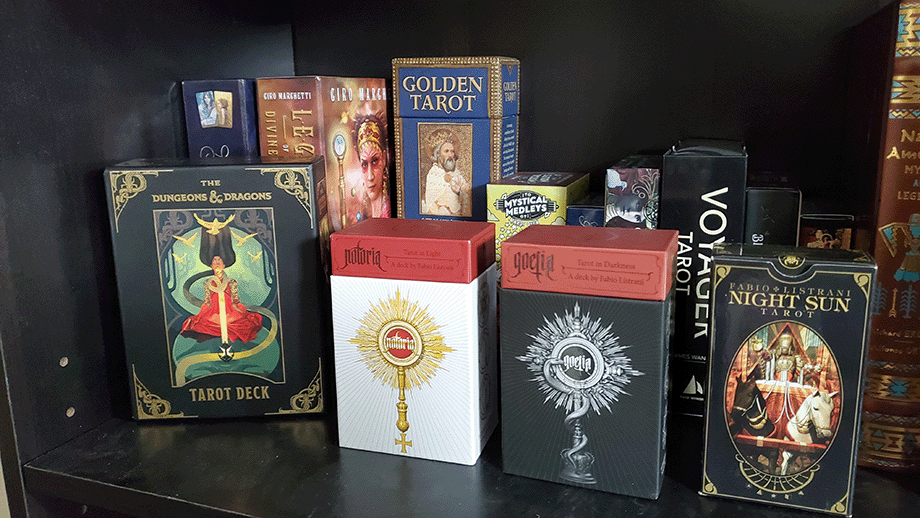

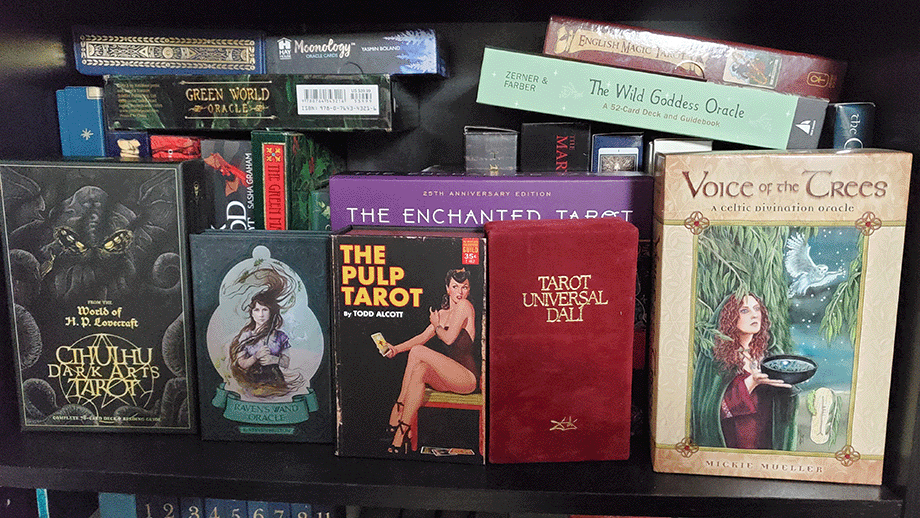

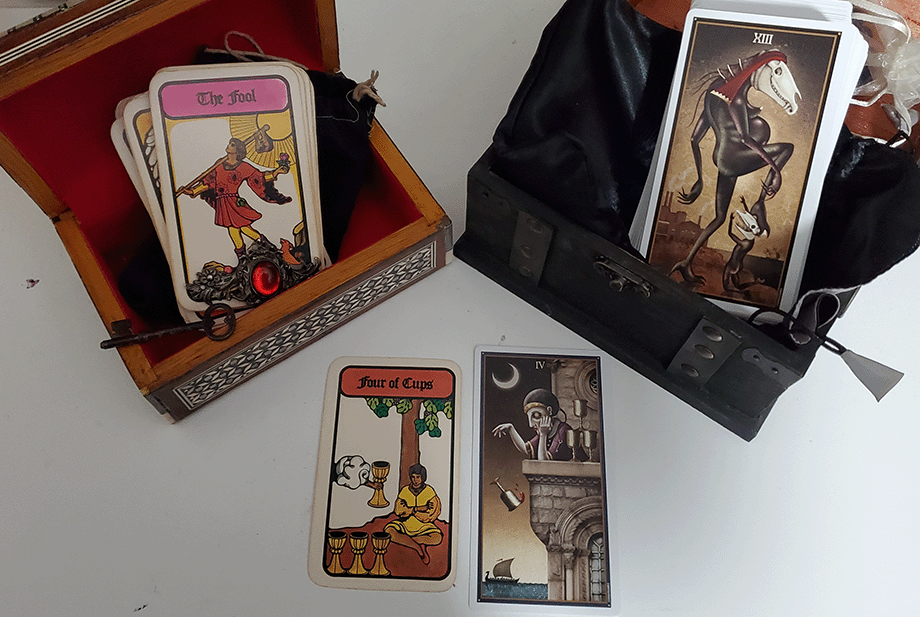

I was pleased this year that a big part of my holiday haul were several new Tarot and Oracle decks. I possibly have suggested that I might have a bit of a Tarot problem (not enough shelving to begin with) , but if a deck presents me with attractive artwork that resonates with my personal tastes, I will likely eventually add it to my collection.

On the other hand, if the artwork doesn’t speak to me, then I will leave it, regardless of how popular it is. For example, my only version of the Tarot of Marseilles is a digital one on my phone and tablet, because frankly I think these cards are butt ugly. I realize that they are the final form of many copies of copies made from woodcut blocks, to meet the demands of Tarot players from the Renaissance onward, and that there ancillary use for divination was not considered of prime importance to the printer.

Yet because this deck forms a very important link between the elaborate Italian decks like the Visconti-Sforza Tarot and the modern ones which were typified by the Rider-Waite-Smith, I reluctantly got the Android version from the Fool’s Dog. I cannot warm up to these cards so they will not serve me to read. A paper copy might be something I should have, but so far they are priced highly (to my mind) for something that was never in copyright, and should be available in discount versions. For now, the scanned images suffice for my research work.

For me personally reading the Tarot, or using it for meditation or inspiration or spellcraft, is unequivocally tied to my experience of the images. I am an artist. I experience the universe through the visual faculty foremost. This may mean that with a particular deck, my mental impression of the card does not match the usual and customary interpretation. As I looked through a number of the new decks, and looked for the familiar signposts that I admit to having learned in my early days, I got to pondering that whole proposition.

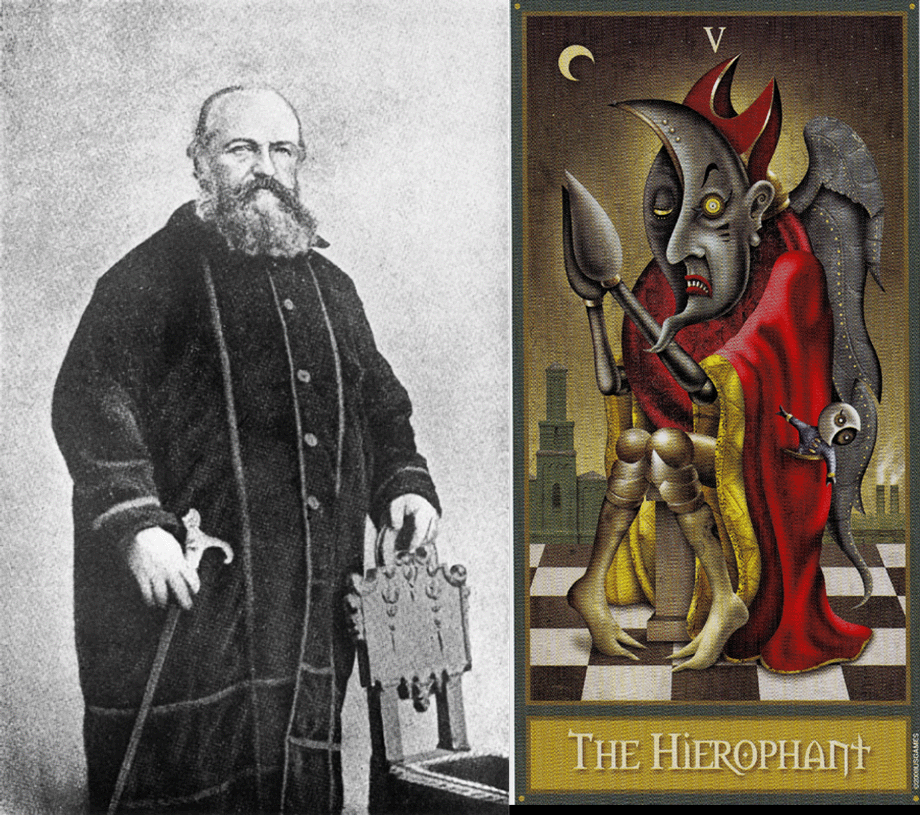

That is, here we have an image, more than likely only about a century old, that has been presented as a definite indicator of a particular idea.

Because Waite said it did. Because he read it from Levi. Levi read Etteilla who probably was extrapolating from Court de Gebelin. Each of these scholars added their own esoteric bent to the tradition, which has no exact reliable origin.

As I haven’t a French edition of the latter tome, I can’t say to what extent this coloring of the Bohemian Nomads, as they are called, comes from Waite as translator, but sadly misogyny, racism, and classism permeate the writings of the 19th and early 20th century occult authors.

This has made the grains of wisdom in such works hard to access, and put off many more modern readers entirely. It’s important to remember to cast such figures and their respective works in the context of their age, and not our own. In a hundred years, we may be seen as utter barbarians.

Many attribute it toward Egypt, but even this is massively miscast (aside from being plain wrong). Crowley’s “Book of Thoth” is more connected with Levi’s “Book of Hermes” and both thereby associate the “Divine Wisdom” with Hermes Trismegistus and the so-called “Emerald Tablet” of the alchemists.

The Emerald Tablet entered European thinking in the Middle Ages through Moorish Spain, and is more than likely a grimoire based upon Greek texts surviving in the Islamic world. So in such a way it does come from Egypt, but not in the way most suppose.

Nor does the confutation of the racial slur “gypsy” with both cartomancy and that ancient land have any basis in fact. The Romani people, we now know, descend from the Indus River valley rather than the Nile one.

But still such stories persist. I trace that to the invention of Curtis Siodmak and the iconic performance of Maria Ouspenskaya in 1941’s The Wolf Man. This one film gives us the archtype of the wizened kerchiefed Fortune Teller with her crystal ball, pronouncing doom to the hero. She was so powerful in the part that she returned for the sequel Frankenstein Meets The Wolfman in 1943.

Whether Ouspenksaya’s character derives from an actual tradition is hard to say. The Wolf Man series were at the tail end of Universal’s golden age of monster movies. Her purpose in the film is expository.

In previous movies the actor Edward Von Sloan would have given us the dire warnings in the guise of Dr. Van Helsing (Dracula) , Dr. Waldman (Frankenstein) , or Dr. Muller (The Mummy). But in 1941 and 1943 the character of “Herr Doktor” was not a type American audiences found comfortable anymore, so the pseudo-Slavic Madame Maleva took up the reins of the person “in the know”.

By the way, the Wolf Man is where we first hear popularly about the Pentagram being a “mark of the devil”. But fundamental Christianity firmly latched onto it as such. Especially since Anton LeVey uses an “inverted” pentagram as the symbol on the Satanic bible. The evil Satanic he-goat fits right into it.

Except it’s not the Satanic he-goat. It’s something called Baphomet, which was imagined by Eliphas Levi. The same Levi who gave us the roots of our modern Tarot meanings. Baphomet is a composite creature, similar to many in alchemical artwork, that incorporates symbols to express certain esoteric teachings. It has been confused with Kernnunos, and Pan, and of course the “Black Goat” in medieval witch-hunting texts. If it has a real progenitor it’s the old Egyptian generative god Khnum.

But the name Baphomet is murky too. It comes from the trials (under torture) of the Knights Templar, to describe a “head” they supposedly worshipped in secret conclaves when they had denounced Christ and trampled upon the cross. The actuality of this Head of Baphomet is by no means an established fact either. Some researchers have put forth that the head is either the folded up Shroud of Turin or a similar sacred cloth called the Mandilion or the Veronica. There is as much proof for that as for the theory that the Templars were secret converts to Islam, and that Baphomet was a mis-recording of Mohamet. Ultimately, like many “confessions” brought about by the insidious methods of the Inquisition, we don’t even really know if Baphomet was simply made up by ecclesiastical authorities who needed a convenient heresy.

In any case, it’s not the Devil, nor does it have any real connection to any devil, demon, or malefic spirit the Christian establishment has seen as persecutorial throughout it’s multiple millennia. But the impression persists. Because somewhere at some time some one wrote it down, and then it became “truth”.

Just like the meanings of the Tarot cards.

Prior to our Good Lady Pixie’s renditions, the 40 pip cards of the Minor Arcana were simply counters, much as any modern deck of “playing cards”.

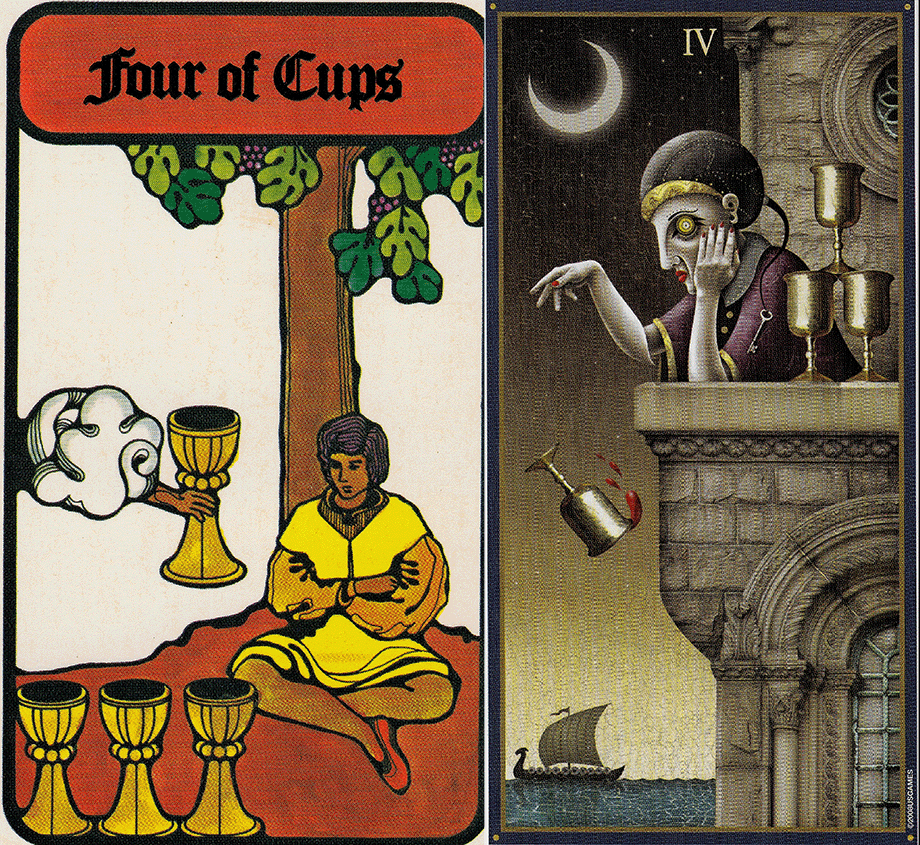

In the first instance our Four of Cups seems to share a common theme – that of satiation, sufficiency, and the need to reject excess. Yet in the Deviant Moon, there’s a touch of deviltry, or at least pique, as the figure casually flicks away the fourth chalice. Or does she drop it in a daydream. Her face (so like a Venetian carnival mask) seems to stare far away, unconcerned, or even unaware, that she has lost one of the cups.

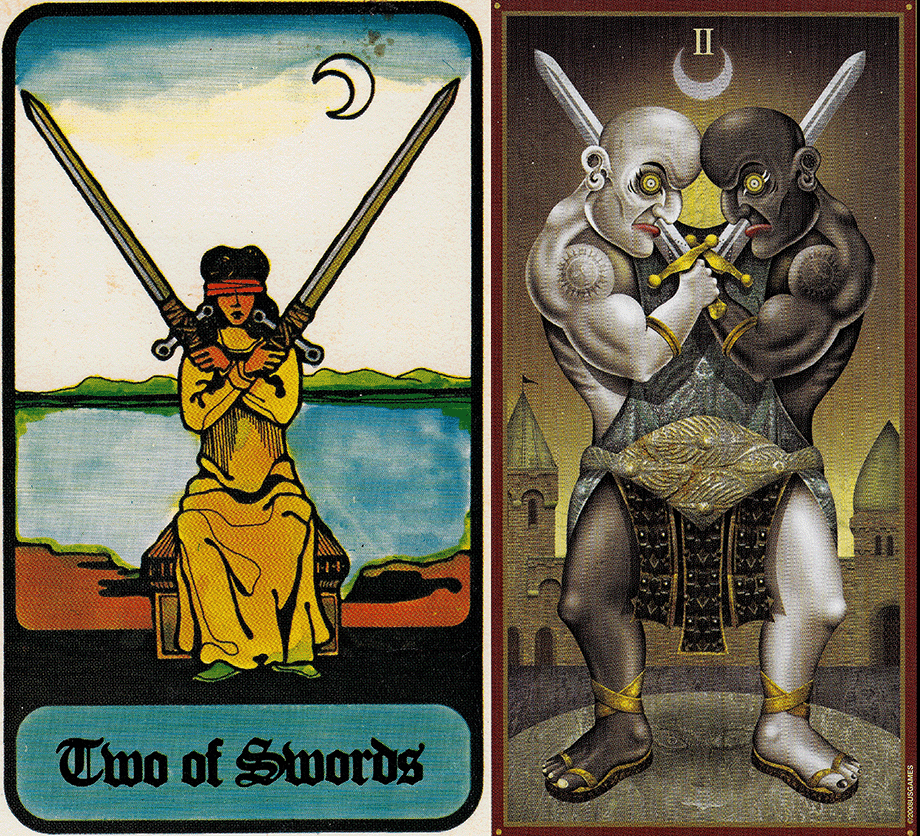

Below is the well known Two of Swords, which often indicates an approaching danger to which the figure is blind to. It speaks of ill preparedness, isolation, and disengagement. Yet the Deviant Moon variant shows us an ettin-like creature, two heads, opposite each other, able to see, but locking in a perpetual struggle for dominance. The design plays off of the Gemini nature of the Deuce. Here the twins are merged. It speaks more to us of inner conflict, indecision, and stagnation. In a way it is not entirely different than the other card’s usual meaning, but yet the journey we take is a fresh one.

Joseph Campbell argues that the suits were symbols of the four estates of the Medieval world. The Wands were the Peasantry, the people working the land. The Swords, were the Nobility, deriving from their historical roles as professional soldiers. The Cups were the Clergy, symbolized by the Holy Cup of the Eucharist, and finally the Merchants were associated with the Coin of the realm.

It’s a pretty picture that would seem to fit, and as Campbell is such a revered source on so many ideas about our human mythology it can be difficult to question. But the connection of the suits with the Elements is equally as strong, and the origin of these cards in Islam, which was not arranged in exactly the same social order, calls it into suspicion. Many sources see the playing card as coming from China, where paper and printing were more extant than in Europe, and traveling with spice, cloth, and secret wisdom, along the Silk Road.

In any case they hit Venice in the 1200s and evolved into the more elaborate trick-taking game of Tarrochi. At this point the simple pips were joined by face cards, and a variable group of special point cards that we now call the Major Arcana.

It is the Major Arcana that Levi gives us values for, connecting it with the Mystic Qabbalah through the ability to give each card a corresponding Hebrew letter. This may be entirely arbitrary. It may be just another attempt to find “ancient wisdom” in something that was never meant to contain it. So there’s something of a good argument that the divinatory cards are only the Major Arcana, and the rest were just along for the ride.

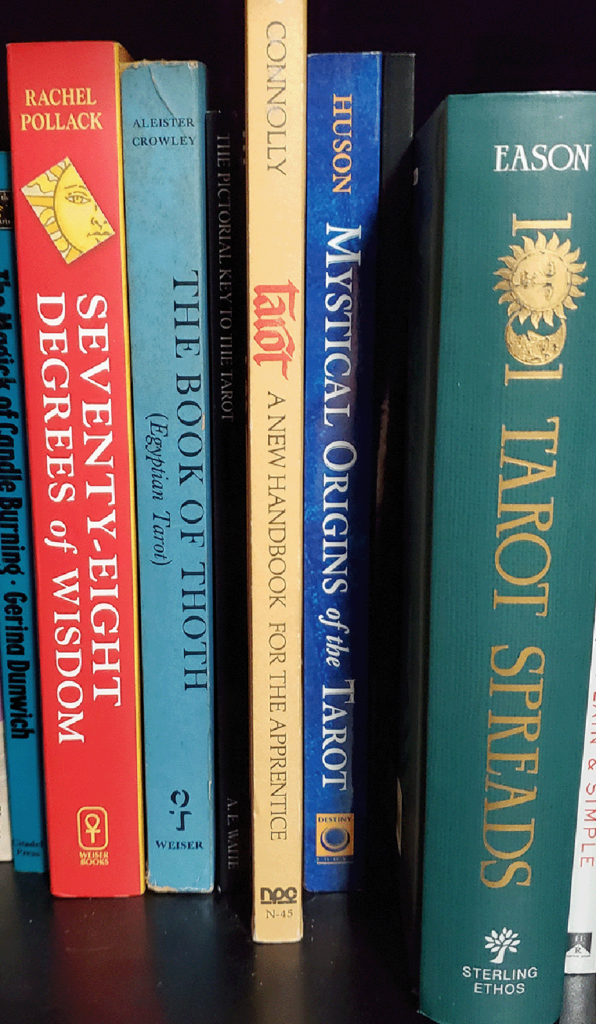

The Connolly and Crowley are among the first. The Connolly was a gift with my RWS deck that didn’t have a book. Though well regarded it is a bit Judeo-Christian oriented for my tastes. Such were the times. The Crowley is a recent replacement of a stolen copy, though it is the same late 70s edition.

Wedged between in the dark there is a copy of Waite’s Pictorial Key to the Tarot, now available cheaply as a public domain reprint.

The rest are some recommended by other writers on the occult, and with the Encyclopedia of Ancient and Forbidden Knowledge, and the Tarot Volume of the Taschen Library of Esoterica, make up the total texts I have on the subject.

I may add one or two more in future,; Dion Fortune, most likely. But a vast majority of texts out there are parroting each other, or one of these, or worse are making bad renditions of Levi’s problematic texts.

On the other hand, there’s a good tradition for using general pip and face playing cards for divinatory purpose, completely separate from the Tarot. Folklorist and podcaster Corey Hutcheson in his book 54 Devils gives us a glimpse into these practices, as well as touching briefly on the Lenormand Oracle, a strange hybrid of playing card and image reading supposedly developed by Marie Adelaide Lenormand, a cartomancer during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

But because the images in the RWS deck give us mnemonic clues to the meanings associated with the Minor Arcana – meanings which may have been a general oral tradition prior to Waite – they’ve become one of the more successful versions of Tarot, and probably the most used for inspiration and elaboration by 20th and 21st century artists and cartomancers.

Which begs the question, if the images and the interpretations are exact from Levi and Waite – why on earth are there so many Tarot decks out there. I have a collection topping 50 and it’s only a fraction of what is available in the mass market. With the RWS falling into public domain a few years ago, Pamela Smith’s icons are showing up everywhere, and clones of her deck can be found on discount store shelves for under $10.

And I strongly feel it is her deck. Like many people today, I fully recognize that the expansion of Tarot as an art form and divinatory practice is largely due to the artwork she created, rather than the interpreted writings of Levi and Waite.

Those writings may not fully hold up to close scrutiny. Through the artwork – which though more than a century old still fascinates and inspires, we can find new vistas, insights, and interlinking interpretations that makes the cartomancer’s art and skill paramount to any dusty old tome.

Because, to borrow from Doc Brown, your future isn’t written yet. No one’s is.

And on that thought I will ask you to come back next week and be a part of my future. As always, thank you for reading to the end.