As last week was a card I associate with Venus, it is logical that this week we explore a card that is certainly the embodiment of Mars. The Emperor, as nominally the mate of the Empress, should occupy the role traditionally ascribed in the Venus-Mars relationship. Again we are tied to antiquated gender dynamics, but again, we are free to turn them on their head, or ignore them completely, if we choose. But because the cards carry this baggage, it is instructive to remember it may be used as tool to interpreting them in context.

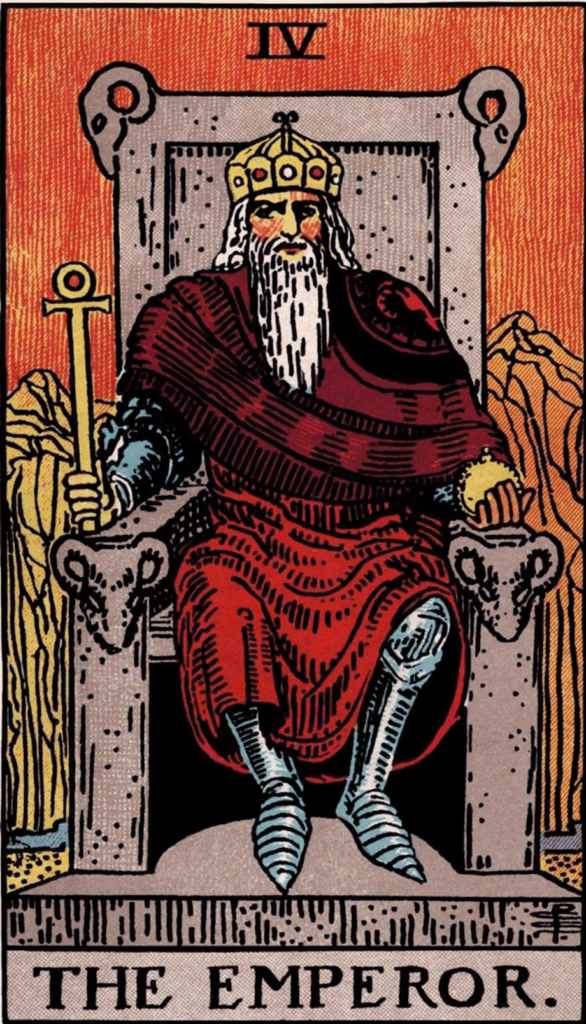

The card as imagined by Pamela Colman Smith shows us an armored bearded man sitting on a carved stone throne. The throne and his mantle are decorated with ram’s heads, connecting us to the symbol for Aries, who is the Greek Mars. In his right hand he holds a scepter that is similar to the Venus symbol (we’ll return to this later) and in his left an orb. These traditional Medieval symbols of royal power are affirmed by the Imperial crown he wears. His garb is red. The sky behind him, unique in the entire Tarot deck, is a fiery orange. The landscape is a sere mountainous desert, with only the hint of a stream running through at the base of those mountains. Nothing grows along it’s banks, indicating that the land itself is barren.

The figure of the Emperor is confrontational. His throne echoes the perch of the Priestess between the two columns. Rather than promising a gateway, he seems determined to block our path and require us to acknowledge him. His expression, might at best be considered dour, but often it seems as angry as the red sky behind him. He seems frozen in this pose, a perfect rendition of a Gothic decoration, down to the clunky arrangement of his armored feet. He might as well be a funeral brass as a person.

As the Empress is the mirrored manifestation of the Magician’s desire for structure and form, the Emperor offers a dry rigidity to the fluid mysteries of the Priestess. She is the Balance between Opposites, the bridge to contemplation of the depths of Sea of Darkness. He is the Monolith that marks the border to the Wasteland. Both of these figures lie between us and extremes that without mediation (and meditation) would destroy us utterly. So even though the Emperor appears to offer nothing but rage and rigidity, we can still be instructed here.

I don’t care for this card much myself, because it always feels like woe and misery. Most of the traditional readings of the card make it almost a symbol of hypermasculinity. In an age where “hexing the patriarchy” is in vogue, it’s easy to regard this card as representative of the tired old men too long in charge of things. That’s a perfectly fair interpretation, and one frequently associated with the Emperor reversed in earlier times. I do feel it presages conflict, if not outright war. It is so Aries/Mars intensive as to be emblematic for toxic masculinity.

We could easily replace his Medieval accoutrements with a beer and a hotdog, and he’d look at home cheering on his favorite sports team. He strikes me as an armchair quarterback, or the armchair general, sending out other people to die on his behalf. This would have been the role of the Emperor in elder days. It is believed that the card character was meant to be Charlemagne, who certainly was responsible for significant bloodshed on his way to becoming “Charles the Great”.

The Emperor is an autocrat. He is a dictator. This we can see from the great stone chair he sits upon. It is designed to be unchangeable with the ages. It is a monument to the war gods. Even though he garbs himself in the royal robe, underneath he still wears his armor. This may indicate subterfuge and hidden aggression when it turns up in a reading. Certainly the presence of this card adds a layer of severity or restrictiveness to the meanings of the cards around it.

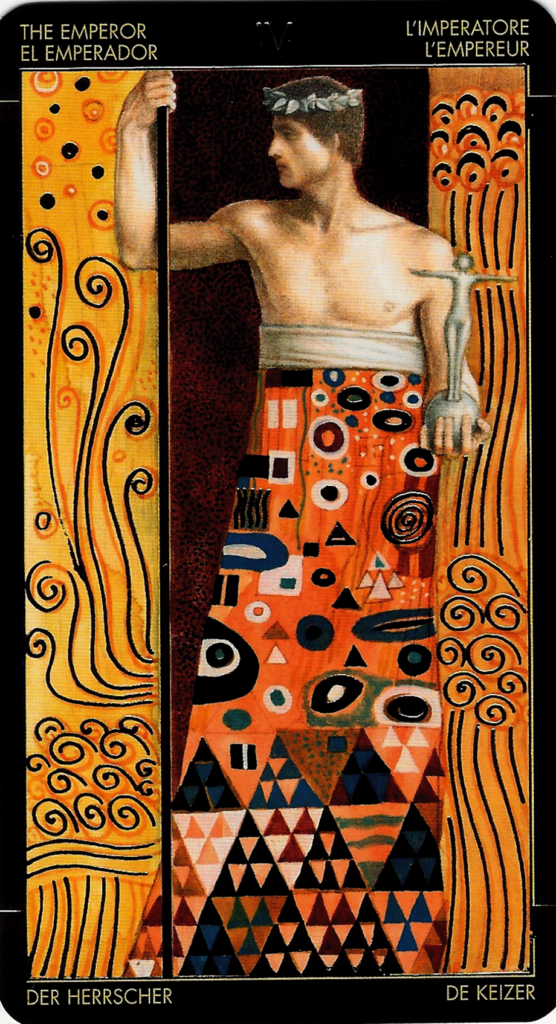

The mountains and the desert are gone, replace by abstract borders that might suggest windblown wastes. The triangles of the Emperor’s kilt against the orange background echo those mountains against the fiery sky. While the figure no longer stares straight at us, there is still a suggestion that he is blocking a doorway. The curious orb design is mirrored on the Empress card of this deck, and essentially uses the human form as a stand-in for a cross or crucifix.

There is guilding on the card that does not reproduce in the scan. It adds a glimmer to all the cards in the deck, and makes them more visually interesting. Klimt used gold leaf on many of his paintings and then painted over it, mimicking the methods of a Medieval illuminator.

In the role of rigidity or restriction, there is perhaps another message to be found. It is this card which firmly declares that the style inspiring Smith with this deck is that of the Gothic or Medieval manuscript. The figures, to this point, might be construed as coming out a more romantic interpretation of that period, similar to that pursued by the Pre-Raphaelites. Certainly there is something of a romantic air about them, but that they are truly Medieval comes out strongly in this fifth card. And it is that Medievalism that we must consider in looking at the iconography of many of the coming cards. It is that period which precedes the Reformation, with a single Christian church dominant, that informs much of the imagery in the rest of the Major Arcana. And that itself is ironic, in that the invention of the cards seems to come from a secular humanist Renaissance.

It is thus a conundrum, if not a contradiction, as to why Smith and Waite chose to make some many of the cards even more Christian than they were traditionally. And at the same time, they plant classical and oriental paganism inside them. It’s possible that Smith, working from a simple brief, let her imagination roam, once the general style was established. Waite clearly was influenced by Levi and the Golden Dawn, and these sources are closet Christian in many aspects, or at best quasi-mystic Judeo-Christian. The dichotomy between maintaining that link to a Kabbalist, Gnostic, or esoteric Christianity, while at the same time trying to divorce from it’s symbols, is why many of the crosses are not crucifixes, and have been altered, to push back against an orthodox Christian theme.

Let us return to the example of the Emperor’s scepter. A scepter is an ancient symbol of royal authority. It is essentially a stylized stand in for the mace or war-club of the old tribal chieftains. As the “rod of rulership” it is metaphor for the potentates ability to physically punish those who disobey him. In Roman iconography this is part of the fasces, an axe – representing the right of the state to execute its enemies, tied inside a bundle of rods – representing the right of the state to beat transgressors. It evolves into the royal scepter as Rome evolves in the Holy Roman Empire. In the Visconti Sforza deck the Emperor carries a simple golden rod, much like that born by the Magician, and in his other hand the Orb.

In the Marseilles decks that intercede between that and the modern Tarot, the orb and scepter are combined (as they are in many post-Renaissance regalia) exemplified by a rod with an orb, jewel, or other more or less round object on top. These are sometimes styled maces rather than scepters, harkening back to their origins in battle gear.

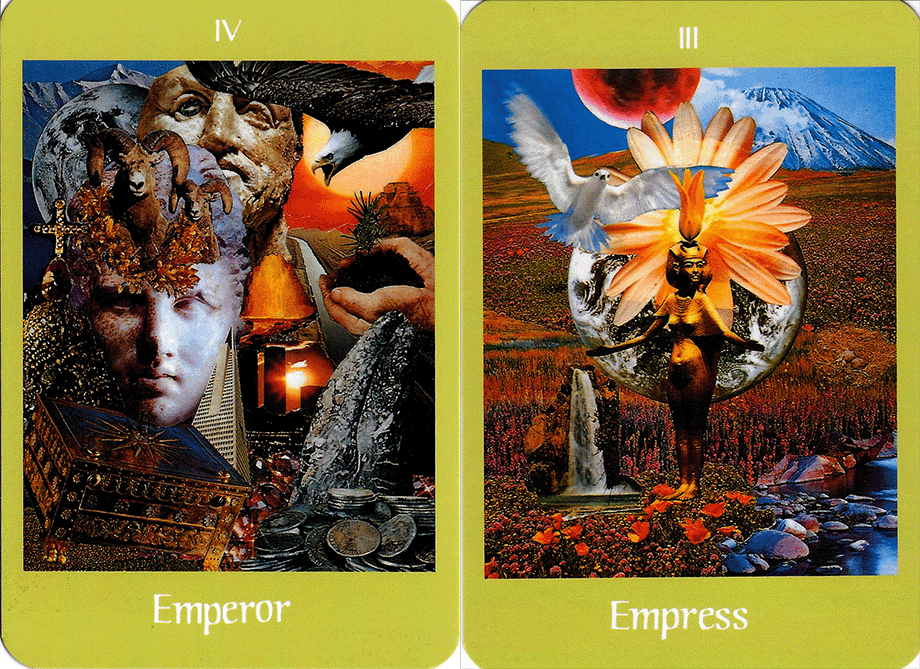

As you can see the card disposes of all the structures of preceding and traditional decks and gives us a space that is both intimate and intimidating. The artist Marie White took 11 years to create. They employ styles and motifs from many world cultures and historical periods. This one, for example, seems to portray an ancient Asian monarch. His various accoutrements however, range in style from 17th century Europe to 20th century Art Deco.

The scepter and orb are gone, replaced by this strange sword, whose scabbard is decorated with the ichthus fish of early Roman Christians. He bears magical sigils on his hand, including the pentagram, and his crown is festooned with dragonflies that would be the envy of a Tiffany or Lalique. A lone flame snakes it’s way up his sleeve, reminding us that behind all this pomp and splendor is still a warlord capable of unchecked destruction. While we don’t see the desert, there is very little living in this image, save the birds that fly in the gray smoky sky. My impression is that they are carrion birds hovering over the aftermath of a battle,.

You can view the entire deck on Mary-El.com. Printed copies were somewhat scarce when I obtained mine. Second editions (or later reprints) are available now on Amazon.

But the RWS scepter is different from these European prototypes. Waite in his documentation calls it a “crux ansata” which essentially is the Egyptian ankh. We’ve seen the ankh before on the Empress card, and one reason that it may be here is that on earlier versions of the royal couple, both were shown with an Imperial Eagle. So when the Eagle is replaced on the Empress card with the Venus symbol, there may have been a conscious choice to add it to the Emperor as the shape of the scepter. Now, perhaps logically this scepter should have been more Martian, given the Mars/Aries heraldry on the throne and mantle, and the context of the Mars-Venus relationship between the two. But changing the Imperial Eagle to the Imperial Ram, is not as random or arbitrary as one might think, especially with other images in the Tarot.

In two later Major Arcana we find the Eagle in company with three other figures, a Bull, a Lion, and an Angel. This figures in Christian symbology are supposed to refer to the Four Gospel authors, and that derives from the four faces or heads of the “living beings” in the Old Testament vision of the prophet Ezekiel.

But these are also seen as being astrological symbols, namely Taurus, Leo, Aquarius, with the Eagle representing Scorpio. Scorpio, in the old Chaldean, was ruled by Mars, as was Aries. So there is a connection between the Eagle and Mars and Mars and the Ram.

On the other hand, the ankh would seem ill suited here, beyond Waite simply wanting to use it. But the fact that it is very stylized away from most depictions of the ankh that I wonder if there is something else to it. It looks to be a circlet of gold balanced atop a T-shape. If we take away the circle, it looks more like a hammer or axe than any kind of cross, and it seems very odd to separate the loop of the ankh from the crosspieces. It’s position atop a long shaft is never shown in Egyptian illustrations.

To imply that somehow this Emperor, who has so many other emblems of war, anger, and sterility, should somehow hold the Key of Life argues for a mystery we have few clues to decipher. Yet even Set, the Egyptian god associated with evil, carried an ankh. Set also was associated with wrath, the Wasteland, and the color red. In ancient Egypt, the scepters have Set’s head, and are said to represent both Set and Khnum, the old Ram god of creation. These are all associations that may be connected to the Emperor’s scepter when exploring this card.

The orb in the other hand is a late Roman convention denoting the sovereignty of the royal personage over the physical world. It probably derives from images of Christ Pantocrator (Christ King of the World) that developed at the end of the pagan Roman period and are a common feature of Byzantine mosaics and Eastern Orthodox icons. Frequently these royal orbs were banded with cross-straps and topped with a cross or crucifix, symbolizing the authority of the monarch through Christ himself, the so-called Divine Right of Kings.

The cross is missing from the top of the RWS orb, leaving us with something that more resembles ah old-fashioned cartoon bomb. The bomb or grenade did come about during the Renaissance, and it certainly would be in keeping with the overall martial character of the card to interpret this as such, though I doubt it was ever intended. Another way to see this ball in his hand is to cast it as a stoppered flask, similar to that used for holy water. In that context, perhaps we have another secreted instance of “water in the desert”.

There’s no oasis here, of course. As noted the rivulet that flows past the foot of the mountains behind his throne brings no green blossoms. It, or the land it flows through, is poisoned. Depending on the version of the deck, I have seen this stream go from blue to grey or from blue to nothing as it goes from left to right. The coloring on this card is unusual too, in that the mountain on our left is yellow, as is the glove of the Emperor, and the mountain on the right is orange, as is his glove.

I can see this as depicting the setting of the sun, or the ending the day or that “dying of the light” Thomas writes about. Taken in context with the change in the coloring of the water, there seems definitely to be a movement from the left side to the right that indicates a worsening condition. If this card were to come up between two others in a reading, it might indicate that the right side card is a deterioration of the situation shown by the left hand card.

The Empress here expresses the Edenic nature of the garden and orchard, with the waterfall in the background. She also, by standing in from of the orb of the Earth, let’s us know that this is a material garden – a real physical experience that stimulates our senses and sates our pleasure.

The Emperor card in contrast shows us works of handicraft and edifice, the machinery of the modern world, imposed over nature without permission, asserting a dominance. Yes, the earth is still there, but it is smaller and less important in the image. There is a small tree growing, but notice that it grows contained by the hands of the Emperor. It is not nature as it is, but nature as He would control it. That old whale in the bottom right I cannot but think is a rough phallic symbol. Or perhaps it is Leviathan, the great monster of the deep spoken of in the Book of Job to express the dominance and power of the Hebrew Man-God. The Eagle and the Ram are here, and as importantly the Dove is with the Empress.

The Emperor image is chaotic and unsettling. The Empress harmonious and well-composed. These are the kind of visual cues I take from any Tarot deck to go beyond what gets written in the book. With the Voyager the mixed images make this a bit easier, but after a bit of practice, any cards will yield similar results.

Try as I might I can find little to nothing to redeem this card. While others may shudder at the appearance of Death or the Tower, I argue that the Emperor is as much an omen of hard times and bad things as either of those two. As the Priestess, in the stars, is hope and reconciliation, the Emperor is, on earth, privation, meanness, and greed.

He is power celebrated for its own sake, and sought for its own sake, and respected only because power demands it.

It’s even sadder, in that there is a suggestion that these woes and worries are inevitable. At the top of the crown, much smaller than we find it on the Magician or Strength cards, is another infinity symbol. We are perhaps doomed to contending with these negative attributes of our society and ourselves in perpetuity. This is the warning of the Emperor.

Rather than ending this week’s article with such a down vibe, though, I offer that the Wasteland of which I speak above is, like the Sea of Darkness it reflects, a path open to the spirit in search of enlightenment.

If you have ever experienced a time alone in the desert, even if you were within a safe distance of “civilization” you may have found yourself contemplating profound and vast concepts. There is something about the emptiness of such expanses that invite our minds to soar. Like an external isolation tank, when we are stripped of the artificial world that most of us find ourselves in, we start seeking some meaning that is not part of that world.

So if the Emperor troubles you, consider him a boundary marker between the strictures and authorities of that artificial world, which he most certainly represents, and the vast untamed unknown. Like the modern manufactured world, the Emperor ties us up with contradictions and prejudices, with things we are told we should believe and things which we are told not to question.

The Wasteland holds mysteries and terrors and wonders and secrets. Beyond the desert and behind the mountains you may find the source of that stream. You may find something else entirely.

On that boundary, the Emperor, impotent, is forever bound to that stone chair.

You have the freedom to walk around him.

Next week we will address another difficult authority figure, who much like the Emperor seems well out of place if we only look at the richly decorated surface Smith has given us. The original name of that next card, the sixth of the Major Arcana, was simply, the Pope. It was seen in that very Catholic Christian context throughout most of Tarot’s history.

In the post-Victorian revision, he has been restyled the Hierophant, a word which means more interestingly Keeper of the Secrets.

I hope you’ll join me then.