This article was originally supposed to be focused solely on the magical ingredient in the title. However, recent events here in Houston have inspired me to go a bit afield and discuss something very important in regard to magic, ancestors, and the rights of peoples and cultures.

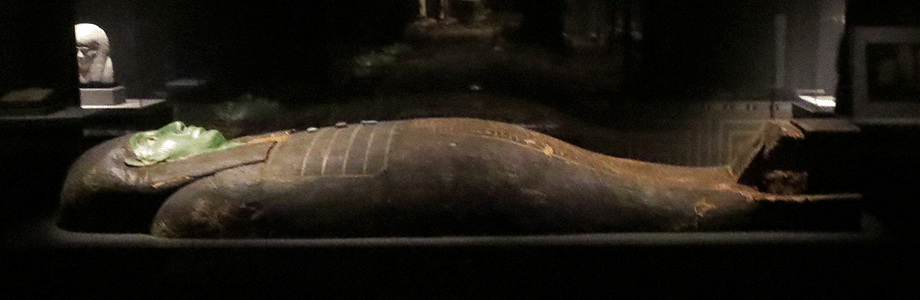

Last week a rather unusual Egyptian sarcophagus that had been displayed at Houston’s Museum of Natural Science was repatriated to Egypt. The mummy case was a staggering 9 1/2 feet tall and sported a bright green face, leading to it being nicknamed the Jolly Green Giant. My good lady wife and I have seen this case multiple times during visits to the museum’s excellent Egyptian Hall, and we joked about that being one of mine due to the size.

It’s tragic that it was discovered to be stolen from it’s tomb, and had wandered the world through one elicit buyer and another, until the final owner – who may or may not have known it’s provenance -loaned it to the HMNS.

I imagine there’s an extensive audit of the rest of the museum’s collection going on right now, and the pieces across town in the Houston Museum of Fine Art are doubtless receiving equal scrutiny. And they should be. As should every collection in any country besides Egypt herself.

This is a sticky point for artists, archaeologists, diplomats, and the citizens of the world’s various local and indigenous cultures. It is something we need to pay particularly close attention to. If the most reputable museums in the world can be seen to participate in the illegal trade of art and antiquities, then the entire context of the museum system begins to unravel.

These are big questions.

I have had the great good fortune to see Egypt’s antiquities in the old Cairo Museum, and I hope one day to visit the new Egyptian Museum which is state of the art in both education and preservation.

I have also seen seminal pieces of Ancient Egyptian history and culture in the British Museum, the Louvre, the Musee de Beaux Artes in Lyon, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and our own HMNS here. The Met was guilty of purchasing a looted sarcophagus from the same ring of thieves that sold the Giant that was in Houston. It has also since been returned to Egypt, and the Giant’s recovery was a part of that extended investigation.

There’s shaky ground here.

The Met also has a hall dedicated to the Temple of Dendur which was “gifted” to the United States in 1965 to keep it from being swallowed by the rising waters of Lake Nasser. Like the Temples on the island of Philae, and the Temples of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel, this little piece of ancient Egypt was rescued by international efforts, and now has a permanent home on Fifth Avenue.

There are a number of other pieces that were gifts or on loan from either the nation of Egypt, or other museums and private collections. The same is true for the art and antiquities of the other nations and cultures that are in that museum, and other museums around the world.

While we can establish an authentic, and hopefully amiable provenance for Dendur, the same can’t be said for items in the British Museum and the Louvre, which are unquestionably the results of imperial pilfering in the 18th and 19th century. Much of the collection in London can be traced back to Giovanni Belzoni, a former circus strongman that can only loosely be termed an “archaeologist” . While his contributions include the acquisition of giant statues and numerous attractive artifacts for the museum, he is known to have literally trampled on the mummies of the tombs he “discovered” in a search for the shinier prizes.

Another sticking point with the Brits is the Elgin Marbles, so called because Lord Elgin paid to have them collected from the Acropolis in Athens, where they had been lying in pieces for some time, and crated up for shipment back to Merry Olde England. The present government of Greece would like them back, thank you very much, and they have been trying for ages to get international law on their side.

Basically, if you have gotten hold of something that was discovered or stolen in the years after WWII, the international laws and treaties recognize this is bad, and will prosecute, as well as seize your ill-gotten gains and return them to the rightful owner.

But if you happened to be an expanding imperialist nation-state doing it up until the end of the 1930s, the rules are a bit murkier.

The Elgin Marbles are a Greek antiquity. There can be no argument about that. They are the fine sculptured pediment and frieze from the Temple of Athena Parthenos (the Parthenon) on the Acropolis Hill in Ye Olde Athens that was blown apart in 1687 during one of the numerous wars between the Greeks and Ottoman Turks.

But in 1800 when Lord Elgin had them transported, the government of Greece at the time was Ottoman, and they didn’t particularly care, and only when a natively stable Greek government came into place was the issue brought forth. Talks apparently are ongoing even now, to have these returned to the Acropolis, but there are several significant considerations rather than just their illegal taking.

First of all, people come to the British Museum from around the world to see the Elgin Marbles and Egyptian and Mesopotamian artifacts. I did. It offers an ability for people to get up close and personal to the remains of a culture that otherwise they may only experience through a book or a TV program.

There is also the argument for preservation. This is even more complicated. Let’s just start with events of the last century. During the past 50 years, radical Islamic factions have knowingly destroyed ancient temples and artifacts from non-Islamic cultures because they violate the Quran’s ban on idolatry. Let’s suppose that the political tides brought such a group to power in Egypt. It is entirely possible that the safety of that nation’s heritage might reside in what is left in museums outside her borders.

In fact, the British Museum, the Louvre, and other prominent museums assisted in the removal and temporary curation of many irreplaceable artifacts from Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, fearing the storm of war would destroy them, or that they would be systematically looted by government officials desperate to fund their military campaign. I don’t know to what extent these pieces have been returned. The stability of the region is not by any means certain.

And it’s not only religious iconoclasm that is an issue. Mao’s Cultural Revolution practiced the same kind of eradication of Buddhist and Taoist art, architecture, and literature as it rolled across China. The Nazis seized works in museums and collections throughout Europe and Africa. The so-called “decadent art” of the impressionists and moderns was ordered destroyed. Some of it only survives because prominent Nazis took it for themselves, and it was later found by the Monments, Fine Arts, and Archives program.

So there is a legitimate consideration for the purely humanitarian goals of preservation, education, and access.

Weighing against this is that very many of the disputed pieces are taken from the so-called “developing world”. That is, basically countries where the indigenous people were non-whites, and their governments were potentially corrupt, and the citizens extremely impoverished.

Looting of the tombs in Egypt is an industry that dates back to the Pharaohs, and was a cottage industry for the disenfranchised even then. When colonizing Europeans arrived at the end of the 1700s, they simply switched to selling to them from the earlier invading Greeks and Persians.

In the later 20th century it became harder for the worker on a dig to pocket a piece of jewelry and sell it to a tourist in the Cairo bazaar. They search luggage at the airport -everyone’s luggage. Still, even today, Egypt is a comparatively poor country, and money talks.

The people on the lowest part of the ladder get a few pounds, enough maybe to stave off hunger for the family for another week or so. By the time it reaches the black market in Europe, Asia, and America, millions are being handed around. The largely white imperialists are still at it, and still patting themselves on their rich backs for it. One might even argue that the person who bought the Giant and loaned it to a museum was expressing exceptional hubris.

I’m going to bring this back around to the “graveyard dirt” thing, now.

The use of earth, usually taken from the top of a fresh grave, or dug out from an abandoned cemetery or the grave of a specific person (like a child or a criminal) is a staple of magical practice in many folkloric beliefs.

Its inclusion derives from the breaking of taboo. We are taking something from the dead, or at least from the place of the dead. We have something that doesn’t belong among the living. It belongs to the dead and world of the dead. As a piece of malefic magic we are counting on no good coming from that.

So what then, do we expect when we plunder the artifacts and habitations of the past?

The whole earth is someone’s graveyard. In the eons that it’s been here, countless multitudes have lived and died unknown to us, and the present surface potentially has had a corpse decomposed on just about every bit of it.

Who knows if our looting of that graveyard in the form of petroleum is not now reaping a toll on our own future?

But more specifically, how can we continue to expand our knowledge of the culture and history without trampling on the bones like our predecessors did? Archaeology, even at it’s best incarnation, is tomb-robbing. Even if it is being done by the local native people, under the aegis of the local native people’s governing authority, the dead are still being disturbed for no reason other than just our modern nosiness.

We aren’t melting down the golden treasures and packing it back off to Spain, like the Conquistadors did to the Aztecs, but we’re certainly making bank on it in T-shirt sales and plush King-Tut dolls at the Little Shop.

And why is that? Well, because it’s expensive to dig up ancient relics and conserve them and haul them halfway across the world so that people who buy T-shirts and plush dolls can gawk at them behind a glass case.

I’m sure that’s a comfort to Ankh-en-Ma’at. That’s possibly the real name of the Jolly Green Giant. He was likely a very prominent and wealthy priest to afford an outer coffin of such size and grandeur, even if it is just made of wood.

If he resides with Osiris beside the Celestial Nile in the Great Hall by the Field of Reeds, having his name spoken of today will insure he continues on for millions of millions of years. At least that’s how the spell in the Book of the Dead goes. And maybe that’s a fair trade for his coffin being dug up and swapped around like a pricey baseball card.

Our technology is beginning to make it possible for us to address the needs of preservation, education, and access with minimal harm to the remains of the ancients.

Currently the cave of Lascaux where Cro-Magnon man etched greats herds of bulls and horses has been reproduced from LIDAR scans, and the replica, faithful to within millimeters of the actual site, is open to tourists. Tut’s tomb has received a similar treatment, and I believe it is scheduled for a tour at the Houston Museum of Natural Science in 2023. That’s wonderful, as my time in Egypt did not allow me to travel up the Nile to the Valley of the Kings.

LIDAR and 3D printing tech make possible truly faithful, portable, and reproducible versions of sacred sites that are endangered. Where a full physical experience is impossible, virtual reality is being combined with physical simulation to generate an alternative.

I was able to enter the Great Pyramid of Giza in the mid-1990s, climb the Ascending Passageway, marvel at the Grand Gallery, and clamber across the sill into the King’s Chamber to put my hands on the remains of his sarcophagus.

In doing so, my breath and the evaporating sweat from the exertion ever so slightly eroded markings and inscriptions on the great stones in the relieving chambers overhead (well, mine and the thousands of other visitors-I didn’t do it by myself). For this reason, the Pyramid was closed to general tourists in the early 2000s. Like the Stonehenge site in Britain, it is accessed only under strictest controls.

But with some creative use of treadmills, black box style props, and immersive headsets, it would be possible to give someone an idea of what it is like to be in that space. You can even have virtual guides tell you the same lies about the pyramid’s construction they told Heroditus millennia ago. They were still using the same schtick in the 90s, so I assume there’s someone around who can record the patter.

Its not as cool as something like the Starship Enterprise’s holodeck, but as a means of bringing the exotic culture of Ancient Egypt to the masses it can work. My eldest experienced a test version using this technique to re-create the trenches of WWI. She found the experience so believable that it was unsettling.

And we can fund such exhibitions with the same T-shirts and plush dolls we’re selling now, while the dead rest comfortably in their graves. Their names will continue to be spoken for eternity across the bright sparkly wonder of the Internet, and their memories made immortal in bits of binary code.

The code will take up considerably less space, be easily transported and replicated to prevent loss, and maybe someday it can be used on that mythical holodeck.

At worst, in our darkest day when we have reached the brink of self-destruction and all that we are and have done is about to be lost in some great cataclysm, we can beam it out into the stars and hope someone else might remember, and speak our name.

Until, then, it’s a new year. The sun is shining. Birds are singing. Let’s not go digging up any ancient tombs.

See you next week.

Note- The photographs of the Giant sarcophagus here are my own, taken some years ago at the HMNS. While I find it’s journey here to be deplorable, I am happy to have met this part of Ankh-en-Ma’at while it visited and hope his spirit finds peace now that his relic has returned nearer to home.