Having assayed the Threads platform for a bit, I am still not quite sure what my longtime involvement will be there. It waffles from intriguing forum for meeting new contacts to colossal time waster, and not much between. I trust human toxicity and the inevitable need to monetize the platform will make the decision for me soon, particularly with elections coming up.

Be that as it may, one of the most frequent “QT with your answers” themes for October is to list your go-to movies for the season.

Since last week I mentioned my deep interest and ambitions in the film business, I suppose this is as good a time as any to delve into my personal favorites, and why they are so, and maybe connect that up a bit with the usual themes of magic and the occult. I mean, should be easy, right?

In last week’s article I made a distinction between horror movies, monster movies, and slasher movies. This is how I personally break down the overall “spooky weird” film category, and I’ll explain why, but I will say that I don’t know of any official scholarly or critical school of thought to support it. There is overlap. There’s a lot of overlap. But this is how my brain splits them up, and so for purposes of analysis and discussion, we’ll use it, since this is my bully-pulpit. You won’t find it on Siskel and Ebert, or Joe Bob’s Drive-In or Elvira’s Movie Macabre, though I respect and have watched all those sources.

So, first, horror movies. Well, sort of. That term was first applied (and perhaps still is) largely to the genre of films made at Universal in the 1930s and 40s, beginning with the Tod Browning Bela Lugosi Dracula. This, was based on the play version authorized by Stoker’s estate, also starring Lugosi. Following Dracula, director James Whale made Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein, both freely adapted from Mary Shelley’s work, which is possibly the oldest science-fiction novel. Then followed Boris Karloff in the original Mummy.

Well, sorry, I classify these as monster movies. The antagonist is a fantastical creature of some kind – vampire, golem, mummy, werewolf, gill-man, alien, giant bug, or city-stomping atomic monster. The plots are not generally complex (though many remakes attempt to be) and in the end, kindly old Dr. Exposition Character triumphs over the critter through his superior esoteric knowledge. It does vary as the offending critter gets bigger through the threat of nuclear radiation, but still, it’s hardly psychologically thrilling. It’s a good popcorn flick.

So what then do I call a horror movie? Well, something that’s really unsettling. Yes, the antagonist can still be a supernatural entity. They frequently are, but what it is, and how it works, inspires genuine fear. It has to literally keep me up at night, or at least, make me turn more lights on in the house.

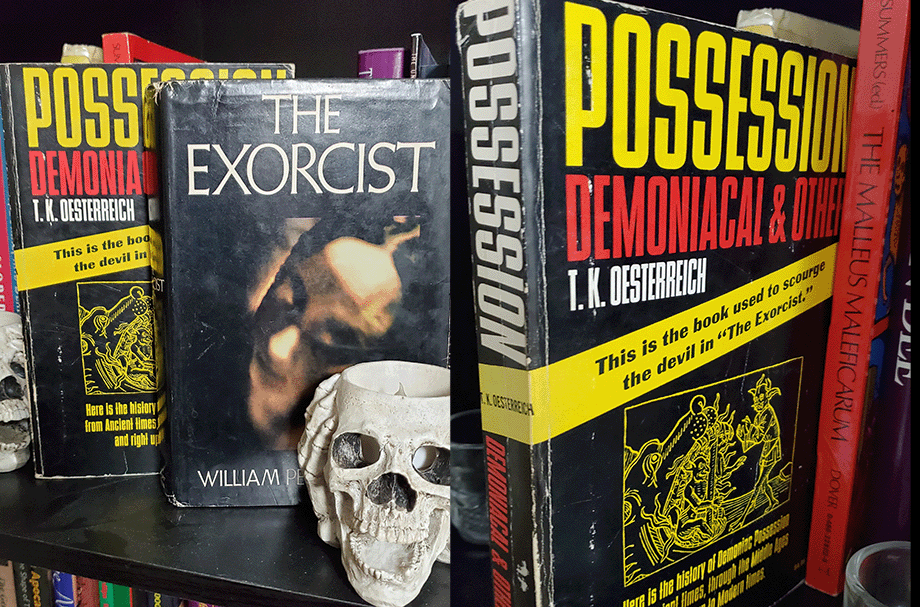

Many of the cases it documents as possession might today be considered schizophrenia, or other forms of delusion or mental illness. As science took hold of medicine, supernatural agencies were relegated to the realm of the non-such. My college psych professor had a good sense of humor about it. The multiple choice question about what modern psychiatric and psychologic practice use as a standard reference text included the Maleus Maleficarum (seen next to the Possession text on my shelf). While the correct answer is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, DSM for short, there was a time in history where the Maleus was the defacto means of determining if someone was a witch or under the influence of infernal forces. It’s a fair point to make that at the time I studied psychology in the 1970s and 80s, the extant version of the DSM including homosexuality and transexual behaviors as mental illnesses. The previous version, only updated in the mid-60s, give us the words imbecile, moron, and idiot to refer to persons with mental disability impacting the “standard” IQ.

I had though Oesterreich included the exorcism text in the book, but I couldn’t locate it easily this morning. If you are looking for a copy, for whatever reason, it’s in Volume 2 of the Roman Ritual.

The banner entry in this category is 1973’s The Exorcist, based on William Peter Blatty’s equally unsettling book and directed by the late William Friedkin. And yes, when I went back and read the novel, already having seen this movie, I did turn more lights on. The movie itself is very stylized, and as such has been copied in a number of other such films, and TV shows, including several weeks where Diedre Hall’s character Marlena Evans was possessed on the venerable Days of Our Lives soap opera. A fourth sequel is being released this Halloween season, with some of the original actors in supporting parts, and what appear to be very inventive effects. The trailers seem to remain somewhat faithful to what made the original so unnerving.

Faith, of course, is central to the movie. It concerns the possession of a young girl by Satan (at least that’s the initial story) and subsequent attempts by her formerly Catholic now atheist mother to obtain the Rite of Exorcism. One of the best things about this movie is that it shows the rational scientific approach to explaining Regan’s symptoms, and includes the Catholic Church’s policy to not sanction an exorcism until all potential medical and psychiatric origins have been ruled out.

Ultimately the Church banned this movie for good Catholics, citing a number of things that they found more offensive than the Devil himself. But at least at some point there must have been a consultant available. Blatty was on set and his research is impeccable, so perhaps that accounts for it, rather than involvement by the Vatican. But the ritual is fairly authentic based on my own research.

The chief origin for the plot was an exorcism sanctioned by the Vatican in the 1950s in St. Louis. It is believed to have been one of the last official such rites performed, as mental illness became better understood and the use of anti-psychotics allowed many of the symptoms of demonic possession to be treated clinically. But evangelicals have been known to perform brutal exorcisms on the mentally ill, children, and homosexuals or other “deviants” up to recent times.

I always found it curious that in medieval and Renaissance times, when the practice of psychiatry didn’t exist, that witches were not treated by exorcism, rather than being tortured and murdered. If one believed that an evil spirit could take over someone and make them do bad things, why was the witch not extended this mercy? The Church, and the Reformation both saw witches as willing participants, rather than hapless victims, so the ritual to drive out the unclean spirit was ineffective. But mightn’t a few of the thousands who were burned alive have been “under the influence”? Apparently no one considered the question.

On the subject of the Devil, I’ll mention two other 70s era horror movies that scared the hell out of me in my younger days – while at the same time, motivating me toward more research into esoteric knowledge. The first is The Omen, concerning the birth of Satan’s child as foretold in Revelations. This movie sparked the whole 666 thing, at least as it was applied in the late 70s and early 80s and alluded to every politico and would be dictator faster than you can say “Prophecies of Nostradamus”. And of course the need for the mass media market to wrap post-Christian quasi-political ecstatic prophecy with ancient Judaic traditions, evangelical political ambition, and obscure medieval French poetry made for a heady mix. Still, the original movie has some genuinely creepy moments and the internal religio-magic system is rather unique.

A less successful piece was The Sentinel, in the vein of Rosemary’s Baby (which is also a wonderful horror movie on its own) concerning the gateway to Hell being in an apartment of an old Brooklyn brownstone. What elevates this is the portrayal by aging veteran horror actor John Caradine as the devil’s doorman.

The chiefly disturbing thing about these movies, and why I call them horror films, is that the dark forces, to paraphrase young Wednesday Addams, look just like everyone else. They are the evil that walks among us in our modern world, and certainly as many were set in the decaying and corrupt New York City of the late seventies, you can read them as social commentary, or at least a psychological attempt to grapple with the modern world not turning out to be the expected Utopia of the flower children.

I’ll backtrack to the monster movies now, and say that my favorites are tied for first. They are the original Boris Karloff version of The Mummy and the 1953 Godzilla, King of The Monsters which is the American release of Toho Studio’s post-war epic Gojira.

The man named Im-ho-tep in real life was a fascinating person, if what was attributed to him is even partially true. He is the inventor of the pyramid, creating the Step Pyramid of Saqqara for his pharaoh Djoser as the first stone building in human history. Additionally, he was considered a great magician and healer, and later would be elevated to demi-god status as patron of physicians. His shrines and temples at Saqqara are found to have hundreds of mummified ibises, the sacred bird of Tehuti, or Thoth, so this is certainly where the “Scroll of Thoth” came about in the movie. The basis for it, as well as the images shown on it, are from the Papyrus of Ani in the collection of the British Museum. We know it better as the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Ironically it is, in fact, a long elaborate magical text for bringing the dead back to life, or at least for insuring that the part of the soul, which the Egyptians called the ka, that represented ourselves was able to re-inhabit his mummy and speak the important spells to reach the paradise of the afterlife.

The chief difference between the Japanese movie and the one I first saw (and I have them both now) is that the US release wraps the Japanese film with about twenty minutes of footage with actor Raymond Burr, who would shortly become famous as Perry Mason. These scenes were shot with a handful of Asian actors in a hotel in San Francisco, and serve to frame the action of the rest of the movie with it’s poorly dubbed scenes. Burr, as Steve Martin (and I always wondered if Steve Martin got his name from that) is an American reporter in Tokyo when the monster rises.

The atomic creature is presented as a mutation of dinosaurs, brought about by American H-bomb tests. Now universally seen as a metaphor for the horror visited on Japan by the only atomic weapons ever used in wartime (and against a civilian population), the truly terrible nature of Godzilla’s destructiveness is not as clear in the US version, and with reason. The movie was scarcely seven years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and in the early days of the US-Soviet atomic cold war. Many Americans did not wish to be reminded of the impact of those events. Many Japanese were still living who could not forget.

Godzilla was successful on both continents and spawned a number of sequels. Going into the 50s, Japan’s relationship with the monster became less clear, and it evolved into a sometimes threat/sometimes champion taking on a host of other giant monsters from pre-history, myth, and outer-space. Rebooted several times it currently is franchised with modern CGI in four US made versions, and is likely to spawn a few more. They just keep coming back.

The Karloff Mummy differs from it’s several sequels in that it is the only version where the mummy is seen out of his wrappings and up to no good. The priest Imhotep (an actual historical personage- in fact the first person other than a king we know from history) was sentenced to be mummified alive for the transgression of attempting to raise the Pharaoh’s daughter from the dead. She and the priest had been romantically linked, but the act was sacrilege. So Imhotep was sentenced to the long dirt nap, and to stop such future sacrilege the magical Scroll of Thoth was buried along with him.

Naturally, when everyone was digging up everyone in the twenties in the name of archaeology, someone opens Imhotep’s tomb, and of course, reads from the scroll.

Rather than being blasted to dust by Isis for such an act, the hapless digger is simply driven mad when he sees the mummy of Imhotep get up and walk away -taking the scroll with him.

Years pass and the mummy directs the son of the man who dug him up to the tomb of his girlfriend, with the intention of summoning her spirit so that they can live forever as decaying corpses. The hitch is that her spirit has been reincarnated in a modern woman, who in the space of a few scenes falls madly in love with the young archaeologist. Imhotep employs his ancient magical powers to draw her away, but she rejects him when he suggests that she needs to die and be embalmed for them to be together eternally. She pleads to Isis, who this time obliges with a handy lightning bolt obliterating Imhotep and the scroll.

It’s a neat movie, with a limited plot, and very little accuracy in terms of Egyptian myth or history, but it did instill in me a deep desire to explore Egyptology and Egyptian magic that remains with me to this day. In the final analysis, the story is simply Dracula, but set in Egypt, and Dr. Van Helsing is transformed into Professor Mueller, in the person of actor Edward Von Sloan who plays both. He also shows up a the “men should not meddle in such things” Dr. Waldman in Frankenstein. Typecasting in the Universal monster flicks insured the audience got the shorthand and didn’t spend a lot of time trying to figure out who was who.

A multitude of sequels followed, lifting the forbidden love and buried alive portions to the mummy of Kharis, who was reanimated through the use of the secret herbal Tanna leaves by a succession of dedicated priests, who at the end of each movie somehow became less dedicated and more self-serving.

Remakes abound. The Hammer one is fairly faithful to the original plot. The Universal one with Brendan Frazier is highly enjoyable and if anything far less historically and mythically accurate than the Karloff one. I try not to let it bother me. But like Godzilla, the old monsters keep coming back.

Which brings us round to the slasher movies. These are based upon the precept of violent dismemberment frequently including on-screen gore. The original, was Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. It’s still my favorite. It is derived from a Robert Bloch story, which is itself supposed to be based on a serial murderer in the Midwest.

There is actually very little gore and violence on-screen in Psycho. It’s implied, and very well. But that’s Hitchcock. Hitchcock was a true genius.

The next prominent slasher film got past implied violence. It was the Texas Chainsaw Massacre. It also was based on a true incident of serial murder, dismemberment, necrophilia, and grave robbing. in rural Wisconsin.

Then John Carpenter made Halloween and the world changed.

Anyone interested in seeing more vegan friendly slasher movies?

Before Hollywood became all activist, much of the blood and guts you’d find in your typical slasher flick was actual blood and guts, collected cheap down at the local slaughterhouse, and liberally slopped around the set. I’m sure there are probably still indie or low-budget genre movies that still use it, but most major productions have replaced the real things with silicon and latex organs. In addition to being PETA/ASPCA and animal friendly, they’re certain more sanitary. They tend to be rather durable. Once the fluids and semi-fluids are washed off, and the phony parts dried and stored properly, they can be used repeatedly on different shoots and different productions.

Real offal had a short and stinky “life” span, though it did have the advantage of drawing real flies (there’s now a special syrup used by the fly wranglers for that. Yes there are fly wranglers. Sit through the credits sometime) ,

Blood and ichor have been replaced by ecofriendly plant-based alternatives. My own first forays were with the tried and true corn syrup and food coloring, but now you can get stage blood that is glycerin based from a cup size all the way up to a 50 gallon drum.

For semi-fluids methyl-cellulose comes in powder form to mix to the consistency required, from slippery and slimy up to full goo blob. This translucent wood pulp material stands in for everything from saliva to alien ooze.

If you can’t track down methhyl-cel, you can use plain ol’ unflavored gelatin. Ooze level depends on the amount of water and the time you boil it. However, if you are vegan, I will tell you that it is an animal product, so consult your local stage supply or the interwebs for sources more to your liking.

Fun fact, in case you didn’t know, the blood in famous shower scene in Psycho is really just chocolate syrup. Stage blood options that were available didn’t keep their consistency and color when swirling toward the drain, so Hitch substituted a can of Hershey’s. It worked far better on the black and white film than the red colored “blood”.

The use of a spray painted Captain Kirk mask on the killer, and the eerie synthesize soundtrack were dictated by the miniscule budget rather than a planned aesthetic. Yet these enhanced the film toward cult status, and spawned a host of imitators. The unkillable Mike Myers of Halloween became the unkillable Jason Vorhees in the Friday the 13th franchise, and any self-respecting holiday that didn’t have an associated slasher flick attached dared not show its face.

In the midst of the copy-cats, Nightmare On Elm Street introduced us to the evil ghost of a child molester who was taking his revenge by killing teenagers in their dreams. Deriving from the urban legend that dying in a dream will really kill you, the pock-faced knife-fingered pursued teenager after teenager as they slept. The imagery was often inventive, and for a while, I had some interest in the genre again, but ultimately even these evolved into self parody, with Freddie Versus Jason, and Friday the 13th Jason in Space.

I’ve never been a great fan of slashers. I saw a lot of them when I was working part-time as a projectionist at the local theater, and they were all basically clones. Escaped lunatic takes vengeance on unwitting victims who are in the wrong place at the wrong time, usually trying to sneak some quick sex, which triggers said lunatic. Freddy Kruger was the first original thing to come along, and it quickly reverted to formula.

Like the Universal flicks of the 30s and 40s, or the giant monster and alien movies of the 50s and 60s, the formula was an effective means of promoting the content to a public who wanted to know what they were getting. These were never meant to be serious fare, at least not in the U. S. More thoughtful and more artful treatments don’t always find an audience and disappear into obscurity.

One of the more imaginative examples of this is The Hunger starring Catherine Deneuve, rising engeneue Susan Sarandon, and rock superstar David Bowie. As a trio of vampires, they stalk the New York singles scene at the height of the disco era, dealing with the problems of immortality and not-so-eternal youth. It features some outstanding makeup work by the late great Dick Smith, and gives us vampires without fangs. It’s a very chic and stylistic work, and still one of my favorites. It’s possible to see it metaphorical, or at least partially inspired, by the nascent AIDS epidemic, but I may be way off base with the producer’s intentions there. It was not as commercially successful as other fare that featured thinner plots and larger cup sizes.

So, if you’re waiting on that hellbroth to cool, or Instacart is slow in delivering your eye of newt, pop up some corn, grab the remote, and go browsing through the back stacks on the streaming service of your choice. I think all these goodies can be found out there somewhere, including other outre works that defy simpler classification like the original Suspiria and The Wicker Man as well as Viy, a 1967 Soviet-made horror film that evokes all sorts of dark Slavic imagery. ‘Tis the season, after all.

In the meantime, I am back to the lab to paint more eyeballs, and stitch electrodes into hearts in preparation for the big day. See you all next week.