Next week, and for the 22 weeks after that, I will be taking one of the Major Arcana of the Tarot and going deep, through my personal perspectives, techniques, and methods for the use of the card in divination, meditation and magic.

In preparation for that, I am going to spend this week’s article going over some things about Tarot in general, so that we don’t have to refer to it every week and can just work with the individual cards.

It’s safe to say that there are hundreds of books about Tarot. Maybe thousands. And that’s just considering the modern stuff that you might be able to order from B&N and the ‘Zon. Going back after works by Eliphas Levi, Court de Gebelin, and Atelier, or the various Golden Dawn texts, may be more illuminating, but are much harder to lay hands on.

You can find Levi in the original French and in Waite’s English translation on archive.org, if you want to dig into it. As I have noted there are a good many warts associated with the work of the Victorian occultists, not least of which are the misogyny and racism characteristic of European 19th century culture.

Yet it is from these tainted roots that the tree of modern Tarot practice has grown, and it is worth exploring that, if for no other reason than to cut away the diseased branches.

I have done considerable research on Tarot in the last several years, and what I put forth here is based on several sources, both in orthodox scholarship and occult studies. In addition to those texts I mentioned as being in the public domain online, I also draw from the works of the recently deceased Rachel Pollack, and occultist and Tarot scholar Paul Huson. I highly recommend their books on the subject.

Firstly, and most importantly, let’s be clear that Tarot are not, and never have been, a secret magical teaching from out of Ancient Egypt, or the legacy of any other lost civilization.

It would be great to believe that. It would make us all feel warm and tingly inside when we shuffle our cards. But unlike astrology and probably numerology, there is no such ancient pedigree for Tarot. The best we can garner for it is an origin sometime in the 1400s in certain parts of Italy.

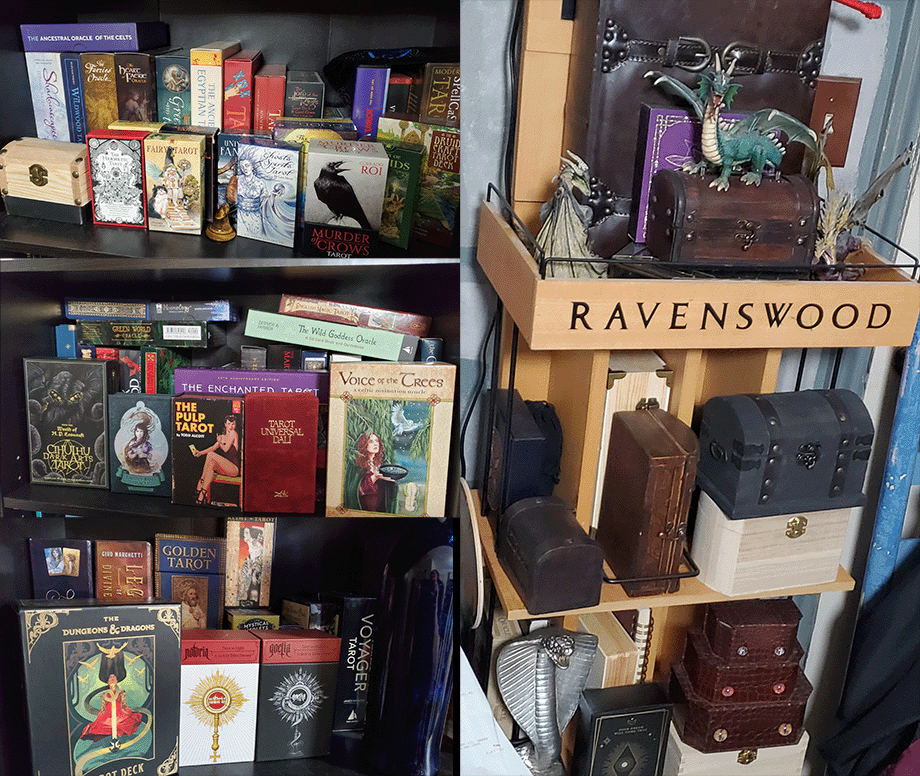

There are about eight more in my Amazon wishlist right now, and doubtless I will run across some more that tickle my fancy when I next make the rounds of the witchy shops on my travels. In the grocery the other day, i saw a set of cards for some sort of matching game that were or Hispanic origin, and I was intrigued with the idea of making an oracle with those.

And yes, I do actually use all of them, from time to time, as they call to me. I am moved by the art. I have none that I don’t like, I have several that I like more than the others (and don’t tell them that), but I am connected to every deck that I own. I do not think I am obsessed. As an artist first, expressing my occult leanings through the most visual of mediums seems obvious. As an artist trained, I am fully aware of the number of subjects that are repeatedly addressed and expressed by artists from the beginning of our human experience to the present day. The Tarot are a microcosm of that experience.

The cards were created for a game, called Tarochi. The game included special cards called Triomphi or Triumphs, which had additional point values. These later called “trump” cards were added to the values of cards in a deck of 56 (4 suits of 1-10, plus 4 face cards). The winning hand had the highest point value.

Sometime in the succeeding century, these extra trumps started to be used for the predictive art of sortilege. Sortilege selects something at random and then attempts to determine a meaning. Originally done by randomly picking a line from a book, usually the Bible, it appears that in the 16th century the cards became an additional method of randomizing, before ultimately having meanings associated with them directly.

Huson makes a compelling argument for these meanings to originate from certain philosophical texts that were prominent in Renaissance Italy. The images, he contends, are a remainder of iconography to be found in the Medieval Morality plays. The threads he pulls seem to connect very logically, particularly with images that are unquestionably Judeo-Christian.

To the extent that these potential sources can offer some insight into the intuitive use of the cards in divination, I may touch upon them from time to time, but my methods are very much driven by a visual experience of the cards. Certainly there are traditionally assigned meanings that I, as well as most other readers, will have learned over time, but I use those as jumping off point.

My “reading” method is to countenance identical cards most importantly – say, if I get the Knight of Cups on two or more cards, then I expect news of a young friend’s wedding, for example. Next I weight the message of multiple cards of the same suit, and then the Trumps and finally any individual minors.

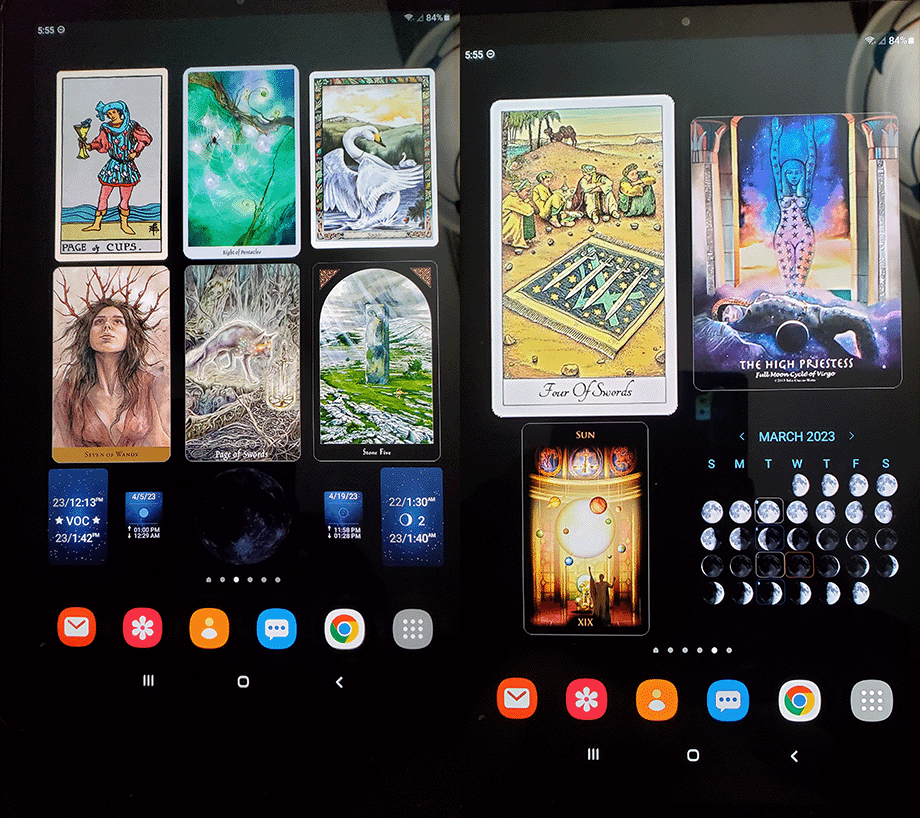

I’ve evolved this practice over the last few years of having these decks on my mobile devices. I haven’t run across it in any texts, but that doesn’t mean that it’s not out there. I know a number of friends on the ‘Gram post options using one or two decks for daily draw messages. I’m just a bit more ADD about it.

Having digital versions of all these cards shows the diversity that exists in interpretation. If I look up the meaning (the digital decks come with a data version of the little book) they vary incredibly for the same card in different decks. So the journey we are about to undertake into my own interpretive method is by no means simply ego. There are as many interpretations as there are readers.

All these apps are from The Fool’s Dog on Android. I don’t know if they make IOS apps, but I am sure someone does. The available decks are all licensed from the publishers, are generally under 5 dollars US (some are a little more) and come with several spreads and a built-in journal function. They can also be enlarged to see detail, and it’s a nice way to try out a deck you may be interested in. I have paper copies of several of these, but some, like Journey Into Egypt are out of print or cost-prohibitive.

Various occultists have added and subtracted from these meanings. If you pick up a deck today, and read through the little white book the meanings you get will likely be abbreviated from Waite’s Pictorial Key to the Tarot. If you want something deeper, Pollack’s Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom gives additional connections, and is one of the better analyses I have seen.

I don’t agree with all of it, nor do I agree with Huson, or Waite, or Crowley, or anyone entirely. I have found, that in the writing of this series of articles, very many of my interpretations of the cards have evolved away from the generally accepted meanings. I can only attribute this to how memory and perception change over time.

In 1972, with my first deck, I had a thin booklet that gave a few words on each card, it’s reverse, and I think about three layouts. Additionally I had the Tarot as described in The Encyclopedia of Ancient and Forbidden Knowledge – or at least how the Major Arcana were described. So much was presented in that book that Tarot was limited, but until 1987, when I received my second deck as a gift, these were the only resource.

During that decade and a half I learned to read the cards like almost everyone does. I laid the cards out, and I went to the book. Eventually I started to remember some of the meanings, and then I remembered a lot more of the meanings.

And then, of course, I started to forget some of the meanings, or at least they weren’t quite as clear to me. So, rather than being embarrassed in front of a client, I looked to the card, and tried to fill in the blanks.

I think that every experienced reader has probably gone through this process. It’s part of the mental alchemy that transforms it from being rote recitation into an interpretative and intuitive art form.

Imagine that a card layout is something like a jigsaw puzzle. The pieces do fit together to give us a complete picture, and like any jigsaw, they fit one way. The difference is that the shapes of the little connecting bits may change each time we consult the cards. That is, what the seven of cups means may alter depending on whether it is next to the six of pentacles or the three of wands. Or if it shows up in a particular place in a particular spread.

The books can only go so far, even when there are hundreds of books. Sometimes they can hint at these combinations and connotations, but the number of possible layouts prevents any absolute.

In the end, the reader is the one who has to find the key in the seven of cups that tells how it connects to that six of pentacles. And that is a synthesis of what the reader has been taught, and what the reader sees. Seeing in this case applies both to a mundane visual assessment of the contents of the image, and to that broader and murkier “gift” that really great artists have.

Over the years, the pecking of Odin’s ravens has altered some of those keys in my head. They’re not out and out wrong (at least I don’ think so) but my understanding of the mnemonic nature of the images on the cards has changed. Also, with the large number of decks I have in my collection, the varying ways those keys have gotten interpreted by different artists has had an impact on how I see the card in general.

Again, I think this is more or less true of most Tarot workers who have been at it a while. We’ve formed our own opinions after year upon year of seeing how these cards play out. Yes, there is the “book definition”, and all of us learned it (or tried to learn it), but that’s not the end of it. If it were, there’d only be one Tarot book, and not hundreds.

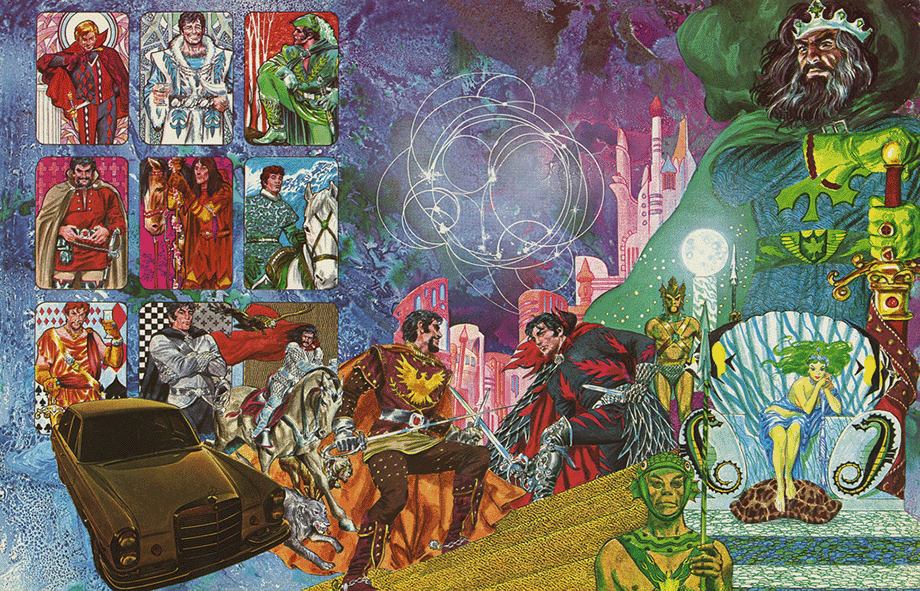

In the magic systems described in the books, there are a set of tarot cards belonging to the family of protagonists. In it the Trumps are replaced by portraits of the members of that royal house. Some of them are shown in the upper left of this image by Gray Morrow from the “Illustrated Zelazny” section on the Amber milieu. The truly intriguing property of these cards, though, were that in the hands of the royals, they could be used to communicate with their opposite members, and even as gateways to where those persons were. Part of the plot revolves around the use of the cards in sympathetic attacks as well.

I won’t drop anymore spoilers. The books are generally easy to find in used stores, thanks to their being a “free gift” for new members of the Science Fiction Book Club back in the 80s. But they had an influence on my own thinking about Tarot and taking it beyond the explicit use as divinatory oracles. Like much of the fantasy and science fiction I read in those days, side by side with occult books, Zelazny’s works had a profound impact on my world view, the experiments I conducted, and the mental language I used to quantity those results.

Tarot derives it’s power from our mind’s eyes. It is a conduit to that penultimate chakra, where we open up our perceptions to the infinitudes of the tiny and the cosmic. It can lift your soul to stand above the universe, and walk over to the next one if you want.

Time to dispel big Tarot Myth Number Two – that the Tarot are in any way connected to the Kabbalah or Judaic tradition. This was almost entirely the assertion of Eliphas Levi, based on a few intimations from previous occultists, but most notably because there are twenty-two trumps and twenty-two Hebrew letters. The Golden Dawn took this and ran with it, and so by the time we get to present day, it’s considered canon, but there’s not any real evidence for it.

That said, there is an Instagram account theorizing that an early version of the Tarot of Marseilles includes secreted Hebrew symbols as part of an attempt to preserve certain Jewish teachings during a time of rampant anti-Semitism in Europe. It’s a fascinating theory, and some of the evidence is compelling, but even the author doesn’t suggest that Tarot itself is a secret Hebrew code. The images cited were, he asserts, added to traditional versions of the cards in this one printing, in order to give covert Jews a means of teaching their heritage. But this is not Kabbalah, nor is it presented as existing in previous Tarot decks, and by his own admission, it does not occur in other Marseilles versions.

The other typical myth associated with these cards is their connection with the nomadic Romany people, called in previous times “gypsies”. The tradition is most commonly propounded by a contemporary and countryman of Levi’s who used the pseudonym Papus. Papus is the author of a text that was retitled in English “Tarot of the Bohemians”, but in the original French would have used the term gypsy.

Atelier also suggested that he learned some of the multiple card layouts from readers who may have been part of the Romany culture. However, the Romany are just another group of people who used these Italian cards for fortune telling. Cards were generally cheap, easily transported, and could be used for games of chance as well as cartomancy. So any group of people who lived a transitory lifestyle might employ them. Sailors, peddlers and merchants, even traveling priests have figured in the spread of Tarot and Tarot lore. No one has a particular monopoly, which adds to the mystery surrounding it’s origins as a mantic tool.

Fortune telling was a good business – as it still is – and a set of cards with possible inscrutable meanings was both more immediate and simpler than complex astrological analysis (prior to computer software, I have spent up to a week calculating the positions and aspects on a single person’s birth chart). Of course, the more exotic the process was, the more the client was enthralled, believing in the supernatural power of the cards, and the reader, and willing to part with their cash.

If you’ve read more than a few of my articles, you know I tend to tear back the curtain on a lot of the occult practices. I have always been, and remain, skeptical of claims which fly in the face of verifiable facts.

Yet I use the Tarot and find it to be useful. I find that in the hands of a good reader, the information it provides is well worth the coin it demands.

I have had my cards read by good readers and bad readers. Bad readers are of several kinds. There are the unskilled, the unpracticed, and the unimaginative. And there are outright frauds.

The frauds are easy to spot. I know what the cards usually mean, if they feed me a line of bovine excrement, I smell it immediately.

The unskilled are those folks who still chase back to the book to look it up. Perchance that’s the novice, the new reader in unfamiliar territory. But it’s as often not a matter of not knowing as much as not believing that they know. This is one of the advantages of Tarot. It’s a shorthand that gives us hints. Given enough time and exposure we stop thinking about what the book is saying in dry and hard to remember text, and start seeing what the card shows us.

Seven of pentacles. The gardener. resting on his hoe, satisfied with the fruits of his labor.

“A job well done. Work rewarded. Plans coming together. Pride in one’s craft.”

Of course, this is much harder to do with a pip-based deck like the Tarot de Marseilles. My brain always switches the pips to the pictures and then I just do that. But honestly, I don’t use a lot of decks without pictures. Had I encountered those decks first, I might have learned them and eschewed the more pictorial.

The unpracticed readers have the skill, but they don’t use it often enough to make the magic happen. While this dulls the memory of the meanings, it also blunts the intuition, the very faculty of taking those memories and making a narrative or context that can’t be derived from the individual cards. If that seven of pentacles shows up next to a three of cups, does that mean it’s a good year for burgundy, or that next week is the harvest festival?

Saddest are the unimaginative. They see the cards right there in front of them and just parrot the same answers every time. The meanings are the meanings and the cards are the cards. So what if the three of cups and the seven of pentacles show up on either side of the Tower. They still mean celebration and reward.

Well, no. No they don’t.

But a good reader can pull one card from the deck and give you a reading that will make your hair stand up.

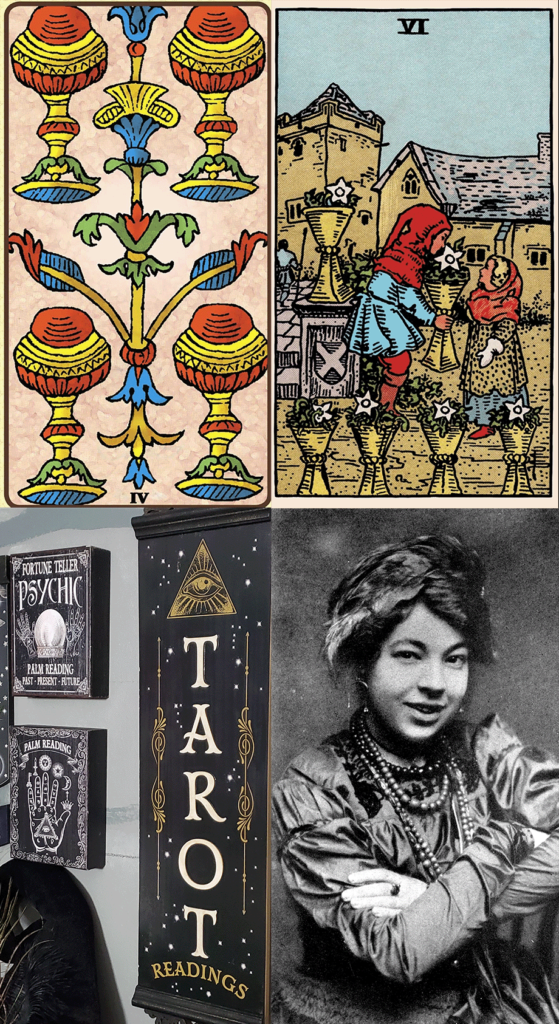

The Tarot deck she is responsible for is one of the most popular, if not the most popular, in the world. Prior to her work, the majority of Tarot decks had only pips, or arrays of the suit symbols, for the minor cards.

Like modern “playing cards” also used for divination, the meanings associated with the individual values had to be rote memorized and parroted back. This skill may have limited the number of active readers, but it also narrowed the space for those readers to engage their imaginations and intuition in explaining the message of the cards.

Smith’s work changed all that. With possibly little to no instruction from Arthur Waite, who commissioned her creation of the card artworks, she came up with 78 distinctive representations of the essential nature of each of these meanings (which were not always clear even at the time).

Any artist working with these themes can tell you what a daunting prospect that is. To accomplish not just the quantity, but to create images that resonate so profoundly that even today “new” decks use her images as archetypes, is a wonder.

And despite the number of folks who use the word psychic hand in hand with Tarot reader, I don’t actually believe that is required.

I’m old school. I tend to reserve “psychic” for things like you see Professor Xavier and Mr. Spock doing.

No offense to my friends who use that term, but I simply don’t consider my own powers of intuition, observation, and imagination to be psychic. I can’t tell you whether the card you are holding up is a star or wavy lines. I am not good at “getting a signal” from someone a hundred miles away.

But give me a deck of Tarot cards, and I will chill you down to your immortal soul. Or at least I used to, which is one big reason I stopped reading for people. But I may be coming out of retirement.

In any case, I thought I would take my readers on a tour through the black morass of my unconscious and show you the Majors through my eyes, with the lore of fifty years of working with and researching these odd bits of pasteboard.

As a basis I will be using the cards of the Rider-Waite-Smith deck, which is probably the most well known deck in the world. It has recently passed into the public domain, which is why the images are showing up everywhere. It is an unofficial standard. The meanings attributed to most of the cards in various versions largely derive from it, and certainly the hundreds of alternate Tarot decks most frequently interpret the images of Pamela Smith, the illustrator who designed it. In case you didn’t already know, Rider was the original English publishing company, and Waite, is Arthur Edward Waite, poet, occultist, and author of the text giving the meanings for the cards.

My first deck was a modified version of the RWS, one that apparently was not modified enough to avoid a copyright infringement in the early 70s when it was produced. My RWS deck was that second one I received as a birthday gift in the mid-80s.

Since then my collection has expanded significantly. I acquire decks purely based on the art. While a few of them have come with expanded and innovative texts, it is the images that I must relate to, and the images that I ultimately use to inform my reading and response.

I will most likely also include the Thoth/Crowley/Thelema images, as they constitute one of the more influential variants. These were created by Lady Freida Harris at the behest of Aleister Crowley, some decades after Smith made her deck, but they weren’t published until much later.

As the muse strikes, I will share other cards from my own collection, bits of my own artwork, and where appropriate, external references you may find useful.

I hope that by the time we reach the end of the summer you will have been challenged to revisit your own cards and look into the symbolism and meaning from your own perspective.

And then maybe I’ll right that book. There’s room for another book on Tarot surely…

Join me next for the Fool.