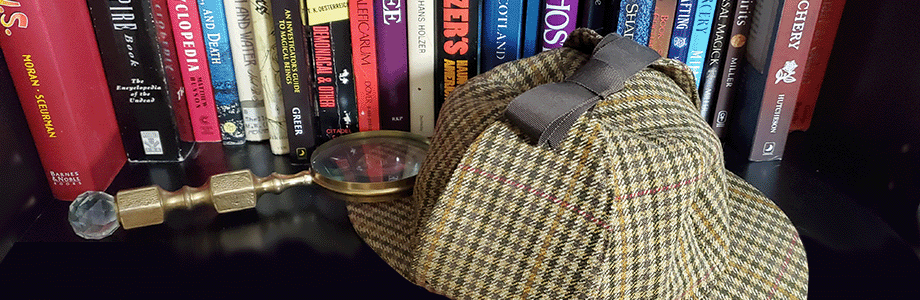

In addition to my penchant for Shakespeare, I spent a good deal of my youthful free time engaged in the adventures of a certain consulting detective residing at 221B Baker Street. Like the works of the Bard, many of Conan Doyle’s stories have been adapted and revised for film, but it is the written word I first encountered, and still connect with.

Latter day incarnations of the Great Detective portray him as an anti-social know-it-all with no people skills. I suppose that’s one way of looking at it. To my semi-adolescent self, this person was, if not a kindred spirit, at least a similar one. His command of vast regions of abstruse information and the ability to rationally synthesize viable patterns from the mundane was a great inspiration to me. I never saw him as cold, rude, or brutal. But then I also may have been an anti-social know-it-all with no people skills.

Imagine you are playing a group guessing game. I’m not sure how many people would remember charades, though it pops up in modern commercials. Now suppose that you have figured out the clues. You know the answer, but you have to wait there while everyone else makes ridiculous guesses.

Sherlock Holmes lived that 24/7. It’s a wonder he didn’t kill anyone. His choice to turn his faculties toward the solution of crimes is showing wonderful restraint.

Modern interpretations make the same mistake universally, and that is seeing Holmes’ best friend and sidekick as being ill treated by the genius detective. The problem with that is that John Watson is not Holmes’ friend. He’s not even a character. He’s a literary device. His sole purpose is to be a mask over Holmes’ thought so that when the why and how is revealed at the end, it’s a wonderment.

Watson is there to give us a version of the story without all the details and clues and trivial tidbits that Holmes sees as valuable. Or rather his job is to make them seem like trivial tidbits. His job is misdirection.

Conan Doyle didn’t invent Watson. He stole him from Edgar Allen Poe. Poe wrote about a genius detective and his thick friend in the first half of the 19th century. The Parisian sleuth C. Auguste Dupin astounds his unnamed narrator by deducing who committed the murders in the Rue Morgue (which sadly about a street and not a morgue).

Poe only wrote two other stories about the amateur investigator before his passing, but it’s enough to credit him with the creation of the detective story, and why the Mystery Writers of America give out an Edgar instead of an Artie for exceptional work.

It evens out, of course. Agatha Christie stole the same device from Doyle to use for Hercule Poirot. Without the dunderheaded sidekick, the Great Detective can’t appear great. You would see how the sausage is made.

Doyle, I will say, shows us how Holmes does it, if only after poor Watson scratches his head and looks dumbfounded at the clues. He spells it out very well in A Scandal in Bohemia. Watson visiting for the first time in a while since he married and moved out, is told by Holmes that he has gained weight, been out in the rain, hired a lazy servant girl, and has returned to his work as a doctor. Watson’s incredulous response is the usual jaw dropped.

“My dear Holmes” said I, “this is too much. You certainly would have been burned had you lived a few centuries ago.”

Holmes then patiently lays out all the little signs that make up the bigger picture. The weight, well he looks heavier, obviously. The servant girl is marked by a cut on the inside of Watson’s boot, made, while scraping off mud; hence the rain. As to his medical practice well he smells of antiseptic, and has dented his hat with the earpiece of a stethoscope. All easily seen and connected dots according to the master.

Watson’s jaw remains dropped. To which Holmes adds:

“You see. You do not observe. The distinction is clear.”

This was a fundamental idea for me. As with any young person who is impressed by a fictional character, I strove to emulate that hero. I endeavored to learn to truly observe.

Humans think they see a lot of things.

Science says that our brains aren’t capable of processing all the visual information our eyes take in, so we fill in the gaps. This is sort of how digital video compression works. A frame shows everything, and the next frame only shows what changes.

Our brain fills in the gaps so that we can function in a visual world without walking off a cliff or driving into a tree because if we had to process all the pixels, we’d never respond in time.

That seems a bit unreal to me, but it’s one of those widely held theories.

We’re really much better at just making things up.

This faculty of imagination would seem to lay at cross-purposes with Holmes’ rationalist approach. But it requires a certain degree of imagination to take all those little bits and pieces and concoct a working theory. Yes, it does have to be strained through the sieve of logic and reality.

“Eliminate the impossible. Whatever remains, however improbable, must be true.”

So the capacity to leap beyond logic and experience a world that cannot be wholly explained rationally can still work in concert with that rational critical world. It’s a matter of knowing when to apply each.

If you’ve gotten to this point and are starting to wonder when I’ll start talking about the usual weird stuff, just hold on. It’s coming.

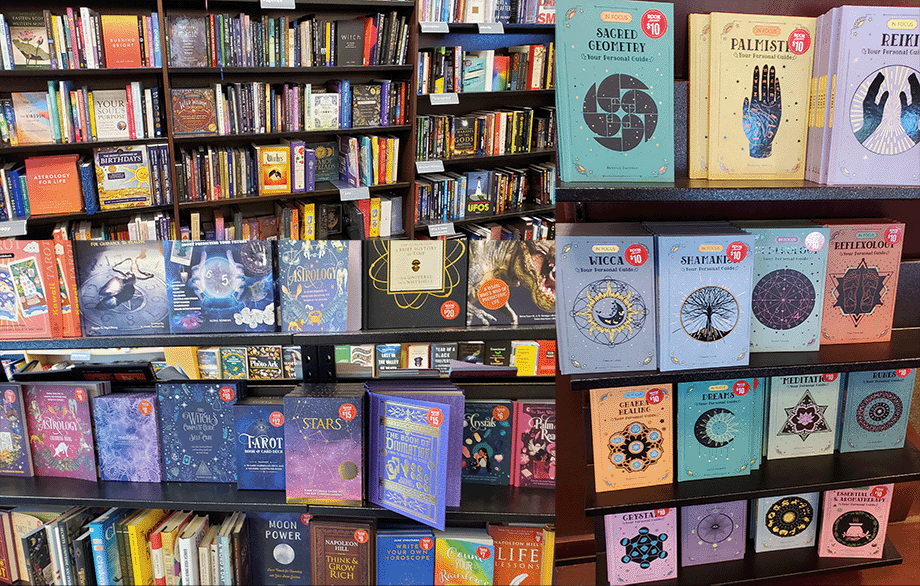

A reliable and effective use of the mantic arts is based upon knowing when to apply imagination and when to refine that information with critical reasoning.

Pure intuition, while it may have the cachet of a psychic experience, is not always useful in the absence of the reasoned context. I’d like to believe that my “gut instincts” will serve me effectively in every situation, but it has been my experience that it doesn’t. And this is following five decades spent honing that instinct and learning how to listen to it.

Sometimes, you’re wrong.

Ordinarily we filter these kinds of things automatically. We experience an input from the beyond, and assay it’s relative chance of being real and useful. But this process can be improved, and the controlled application cultivated.

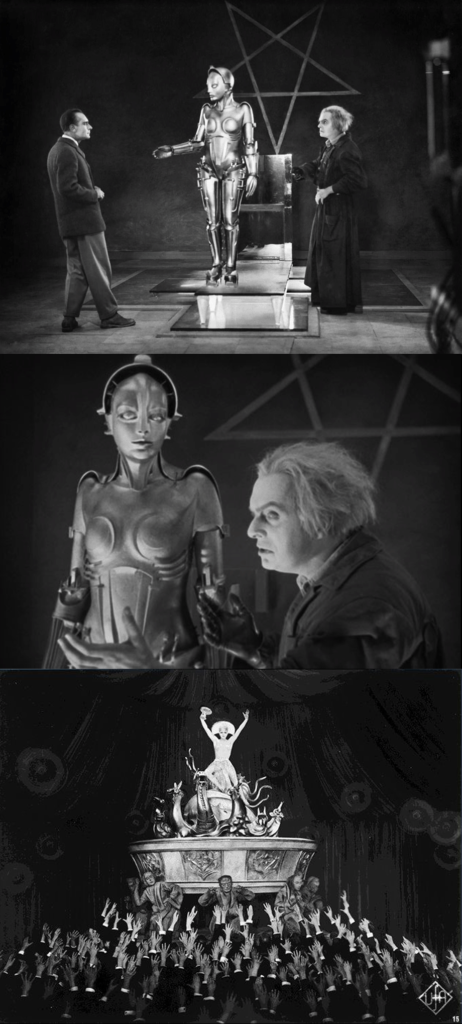

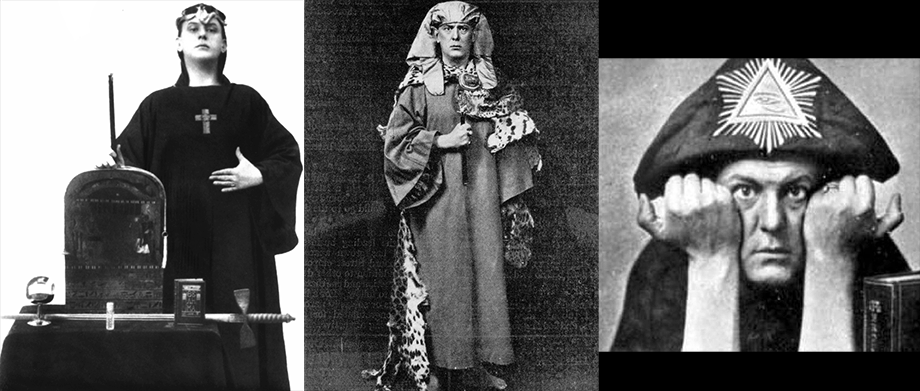

You may know that Conan Doyle was deeply involved in the Spiritualist Movement. It is surprising to a lot of people that the creator of a character so attached to reason and logic would hold such a powerful belief in the existence of spirits.

He’s also known for his staunch defense of the photographs known as the Cottingley Faerie Hoax, and continued to persist in the reality of the Bright Folk. Some would suggest that had he applied Holmes’ methods he could have discovered the hoax. It seems obvious he didn’t want to. Belief can override our senses. We see what we think we see.

We may be doubly damned if we’re used to hearing these kinds of revelations from our own “inner voice”. Some of the meditative practices I have been working with lately involve going deep down into one’s own mind, and then bringing up that consciousness to the everyday. My experiences with this have been startling in the results. I have received “signs and portents” relating to what I am studying at a much higher frequency than before.

Or perhaps I am imagining it. Perhaps it is a trick my mind is playing, or rather replaying. My tricksy brain is externalizing the material I am working with to “create” correspondences in the real world. It is possible that because I am engaged in heavy study of the subject matter than I am subconsciously identifying that material in the world around me. As they say, when you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

But what if it’s both?

What if my brain is projecting the work I am doing through meditation into the world, as a means of improving my perception? In other words, yes, I am seeing signs and portents because my brain is subconsciously engaged in signs and portents. But also, the signs and portents are there, and this process has me noticing them more. It’s really not possible to say objectively if my “heightened powers” are a quirk of neurochemistry or a “real” external phenomena.

And it actually doesn’t matter.

A person with schizophrenia can perceive things that aren’t there. We consider that mental illness in our modern society. In other times and cultures these people were considered touched by the gods, and sacred oracles. And other times and cultures they were considered possessed by demons and burned as witches.

The degree to which our perceived world is a detriment to how we function in society varies from person to person and culture to culture.

Persons on the autism spectrum connect to that “exterior” world very differently than neurotypical people do. Sometimes this can manifest in a preternatural eye for detail, much like the fictional Mr. Holmes. Complex patterns may be observed that are only otherwise discoverable with cutting edge search algorithms. This can be attended by obsessive behaviors, difficulty or inability to communicate emotions properly, and a host of other challenges. These are not the result of impairment, but of a brain that moves differently from idea to idea, linking them in non-standard ways; at least by the “standard” of the general populace.

For a short time Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini were friends. Houdini spent a good deal of time debunking “psychic phenomena” including divination. Houdini had been a stage performer since a young age and had witnessed hundreds of “mind-reading” acts. The trick with mind reading on stage is to start with something general, which is likely to be true for most of the people in the audience. Then you circle in with some details, the letter of a name, a piece of clothing. This is still quite vague, but you start to get a reaction. “My Uncle Henry” someone will shout, and then you keep drawing the circle closer, looking for the mark to give you more clues.

It’s part trick, part observation, and part suggestion. People want to believe, so they’ll let their brains be led, especially if you lead them in a way that can be a kind of hypnosis.

Now if you think this is disingenuous, I invite you to go find an old recording of a TV preacher faith healing in the 1980s. This is exactly the process they are using. 1Obviously I personally believe that the televangelists were as aware of this being a show as the stage magician, but your mileage may vary. Watching the observable practice of both, the similarities are obvious. Were there preachers who believed that their schtick was doing the Lord’s work? I don’t know. Most of them got paid as well as a headliner in Vegas. The extent to which someone who is anxious, or depressed, or suffering from a psychosomatic illness being “healed” by such a practice is equivalent to the audience member believing he received a message from his Uncle Henry. But I am extremely skeptical about the lame walking, the blind seeing, and cancer going into spontaneous remission.

To be fair, and openly honest, when I was reading Tarot for clients, I also employed this technique to some extent. I very closely observed the client as I drew cards and performed the interpretation. You can pick up things from body language, vocal tone, etc. that indicate when what you are saying is hitting a nerve. The setting for a reading is almost universally made intimate, and often dramatic, to encourage a receptive mood in the client. It has the added effect of eliminating distractions so that I can concentrate on what I am picking up from them.

Now some people call this a psychic connection, and I am not about to argue that. I personally don’t consider myself any more psychic than Sherlock Holmes. I know his methods and I apply them. When I get a “vibe” from a client it is because I have spent many years honing my perceptions to pick up those cues. And these cues are vital.

A modern incarnation of the Great Detective was the television series House, M.D. An anti-social iconoclastic diagnostician whose genius was such that it mystified all his associates, Greg House flaunted convention at every turn until he was able to ferret out the mystery disease (spoiler alert: it’s not lupus). House had a maxim that was proven out in almost every episode.

“Everybody lies.”

The Tarot client comes to you either skeptical, or timid. They either don’t believe you or they don’t trust you and in either case you will not get the full story from them unless you employ these deep observational skills.

This is not a trick. It’s not a con. It’s a method to get inside the head of the client and really truly help them, which is why they came to you in the first place. If I had an M.D. I could call it psychiatry and charge $150 an hour. But my parents couldn’t afford medical school, so here I am with a deck of cards, and a spooky knack for reading people.

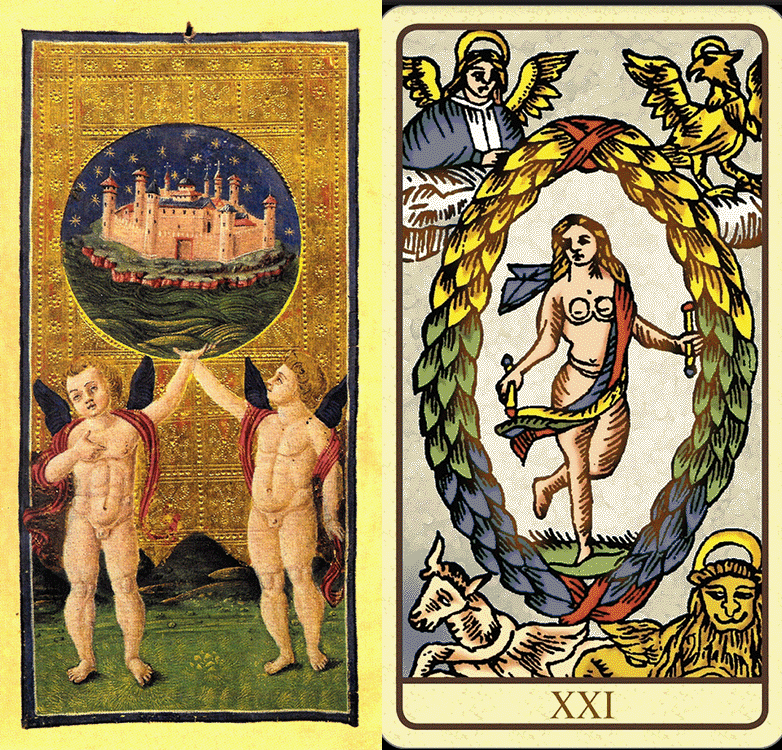

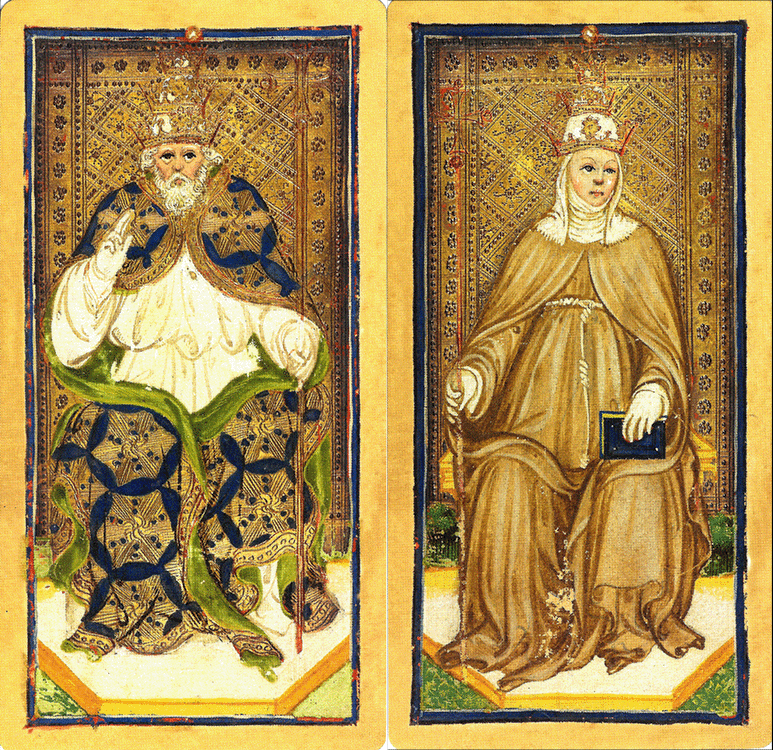

My cards are not mere props, nor is the reading just a fun mask for psychoanalytic counseling. The client and I, in our little purple draped space, are participating in a ritual that is hundreds, if not thousands, of years old.

Ritual is in itself an altered state of consciousness. The roles we both play are not what we are outside the curtain, this event is special, the space sacred, the time suspended. Both reader and client are engaging in a semi-hypnotic symbiosis.

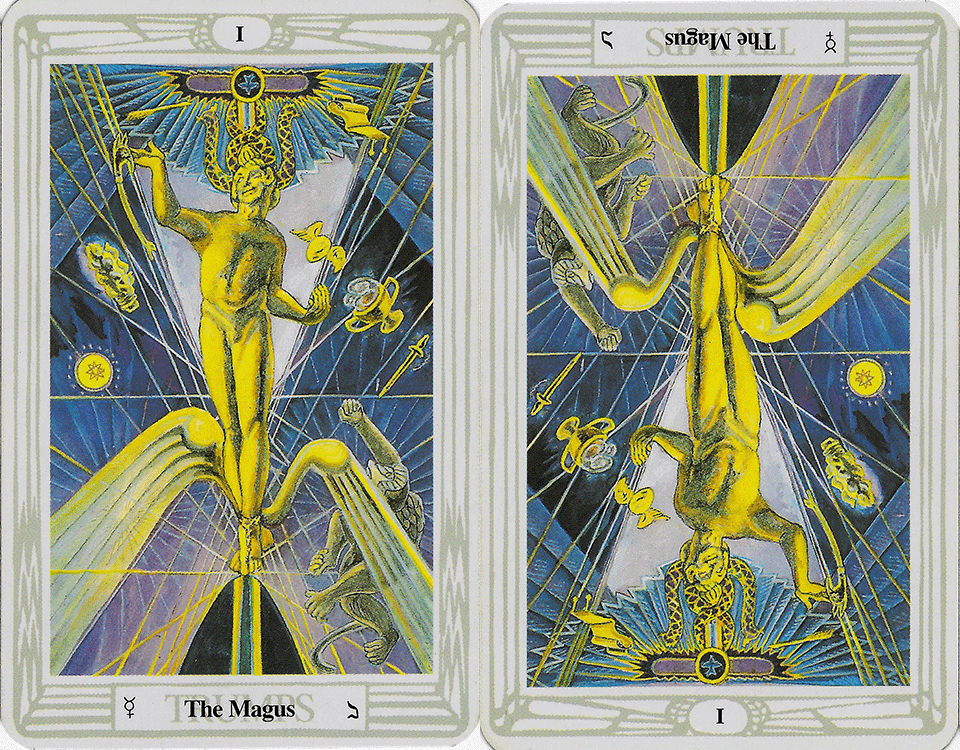

In this state, the interaction of keen observation, willing responsiveness, and the mnemonic and evocative imagery of the cards produce a result that is more than the sum of the parts. The skilled reader will already have a deep understanding of the codified meanings of the cards, but in the moment, they may see something beyond.

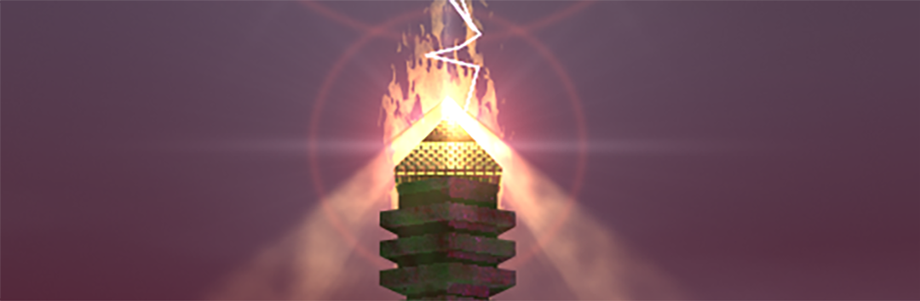

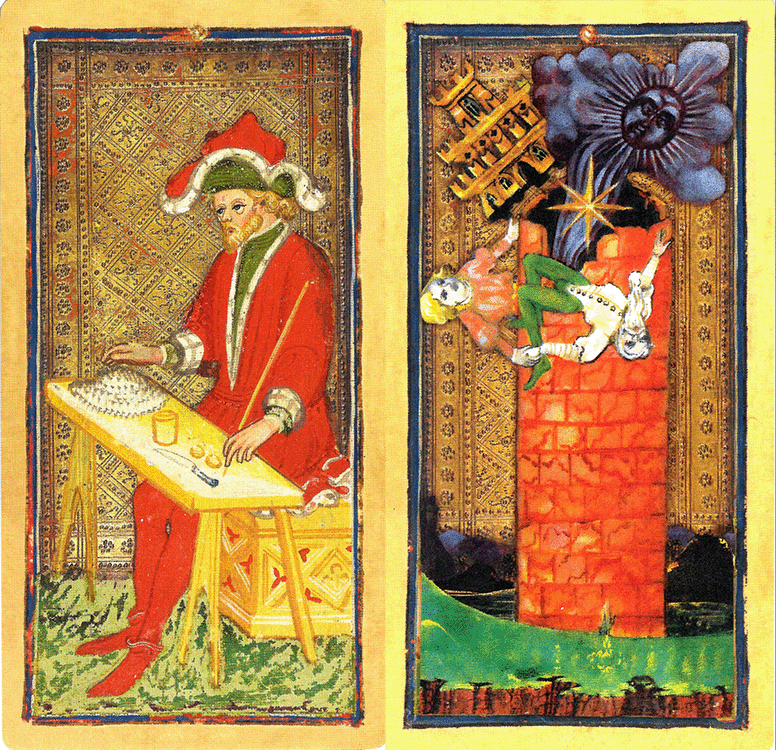

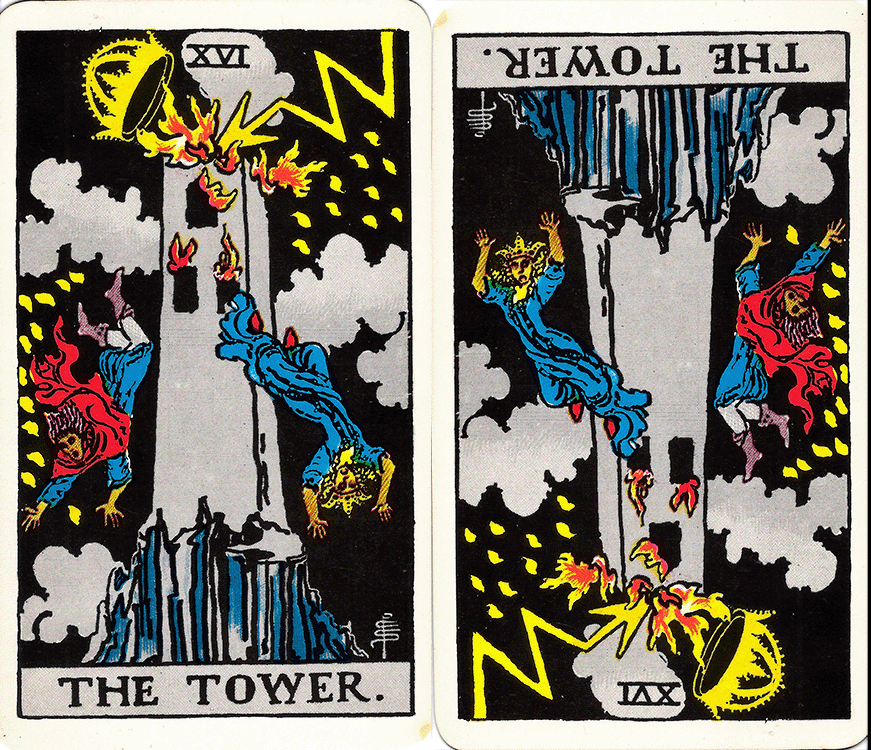

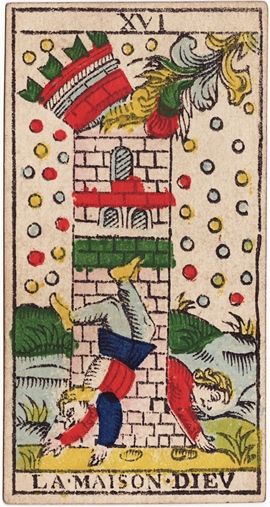

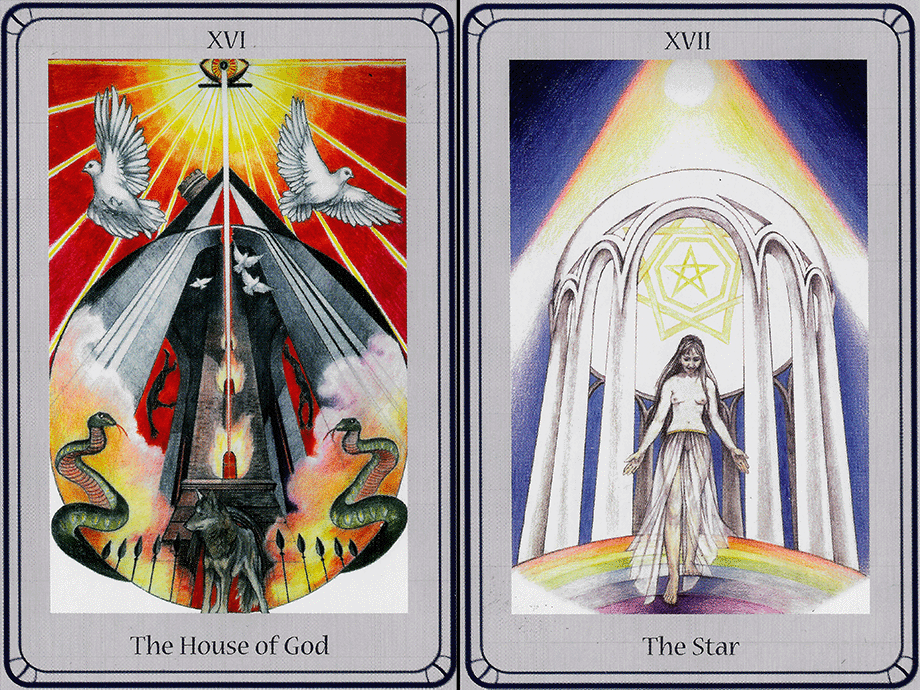

This is also the result of heightened observation. For example, a few weeks ago I did an article on the Tower card, and used an example from my set of the Via Tarot. One of the messages is, in general, the fall forecast in the Tower is redeemed in the Star card that follows it.

Now as I was mixing decks for the article (because I have about 50 and I like showing them off) I didn’t immediately notice an artistic conceit in Via’s Tower and Star combination. The temple shown on the Star card (XVII) is the same as the “House of God” (XVI-the Tower in most decks). On XVI, when the tower is falling, all is in chaos, and the wolf is literally at the door, the viewpoint is close. In XVII, the viewpoint is more distant, the perspective relaxed, and overall feeling much light. Yet this is the same building architecturally.

The dome behind the star is a cleansed and renewed version of the House of God in card XVI. If we step back from the central arch of the Tower edifice, we can see that it is a much bigger building, able to accommodate more entrances. The piercing Eye of Omega has become a gentle nourishing afterglow. Isis approaches us, no longer wearing her veil. The Light that burned and broke is now refracted through the stellar heptagram, and cast as the steps of the rainbow she descends.

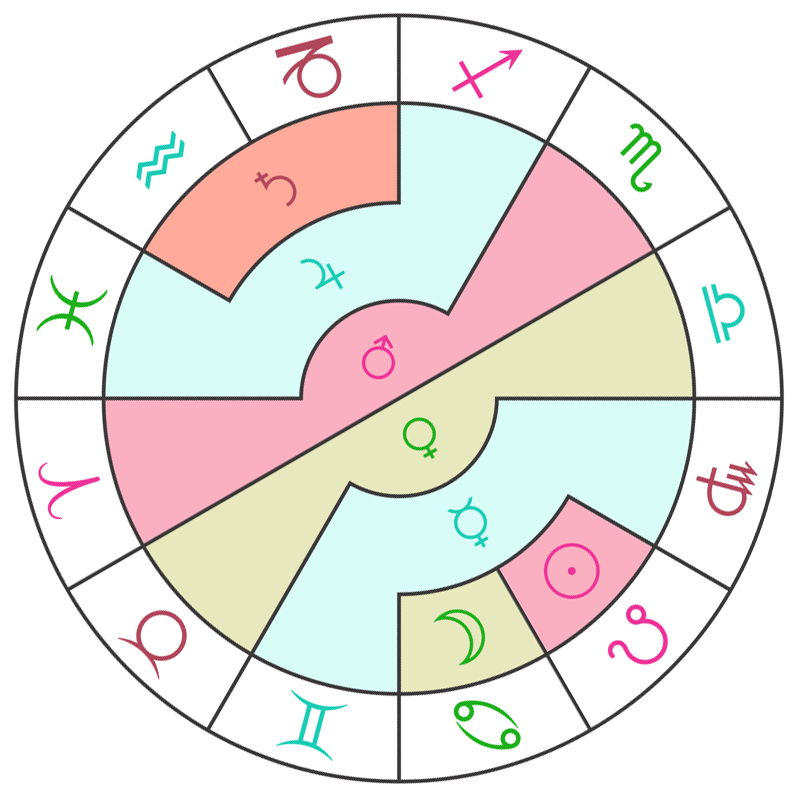

The 7 points of the Heptagram are the old Chaldean planets, – Sun, Moon, and Mercury through Saturn. The twelve pillars of the temple roof are the Zodiac. The Pentagram in center is the Microcosm and Macrocosm, Earth, Air, Fire, Water, and Spirit.

Tarot is a journey through symbols. It’s equivalent to a waking dream. While the images recur, the meaning changes.

So what meaning does that give us? Is this even an intended meaning, or did the artist do it unconsciously? Is my connection a “trick of the mind”? It doesn’t matter if the idea gives me a new avenue to explore when these cards show up in a reading.

I’ve had this deck for the better part of two decades, and I never saw this until I was writing that article. The additional study, contemplation, and multiple exposures to the various cards stimulated a number of new observations.

Some times, even when we observe we do not observe.

And sometimes we take in a massive amount of seemingly trivial data until some trigger causes it all to coalesce into a meaningful pattern. 2Meaningfulness is a relative term. When we are talking about the landscapes of the mind, symbolism has as much weight as literalism We may have symbolic connections that are ours alone and not even fully understood, consciously.

Dream interpretation is a mantic skill going back to the Stone Age. If we don’t know what the flying hot dog going into the train tunnel means, we’ll often just accept someone else’s explanation. It relieves us of the responsibility of uncovering it.

I wonder about the damage done to our psyche when we overwrite the subconscious source code with the wrong answer.

This is aim of the Tarot. It exists to be that one electron spark that starts the lightning strike. But for lightning to strike the conditions must be right. The mind must be receptive, alert, and observant.

The skilled reader will develop a rhythm that achieves these conditions naturally, without stopping to think about “Am I watching their body language?”; “Does this card in this position mean something differently than normal?”; “Am I listening to my intuition?”

For the novice this can be terribly frustrating, and made even moreso by the myriad decks and books on the subject. Even if you have a “talent” for the cards, for reading people, and observing their reactions, getting comfortable with the basic and reverse meanings is a process. It goes beyond just not having to check the book (and sometimes even old hats still have to). It’s about knowing them well enough to see where they sit in context of the a reading. And then once you get that working, you can start to see where they sit in context of your client and how they are responding that day.

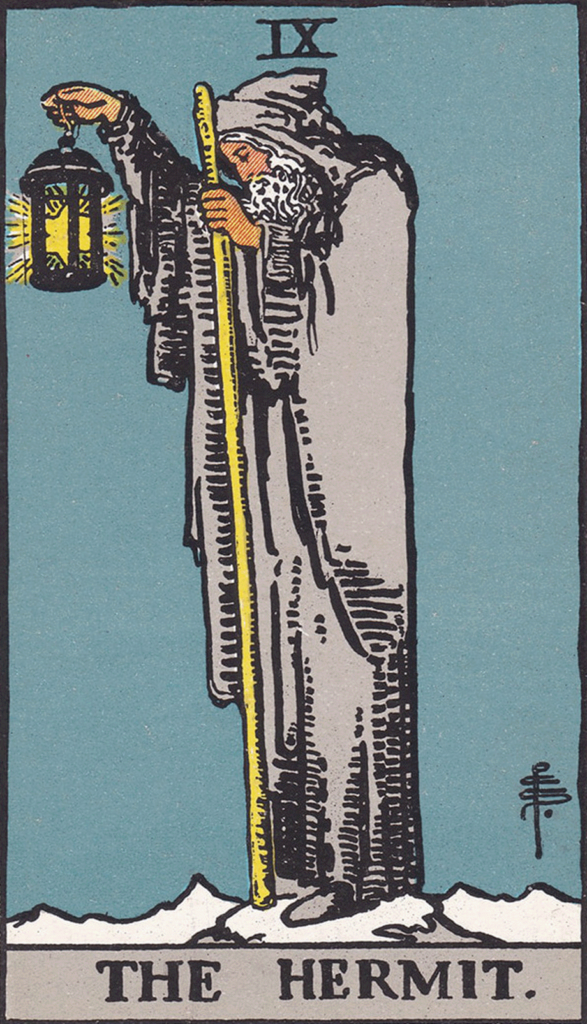

It can help to just start with the Major Arcana. If you really go deep into a standard Waite Deck that alone can keep you busy for weeks. Once you’re happy with that, pick a suit and work through them the same way, until you get all 78 more or less.

Don’t expect to recite the full pages of the text. Get it down a to a few sentences at most, so when that card comes up you know immediately what you are dealing with. That’s actually on Pixie Smith’s cards, which is why the deck became so popular, and why it’s the best “starter”.

Don’t worry about esoteric meanings, numerological, astrological, qabbalistic, or alchemical meanings. Just learn that this card means this, and if it’s upside down, it either means the opposite, or that the meaning is lessened.

When you get past that point, you will start to make those connections naturally, and then be able to expand upon them. And then you can go back and find all those other meanings that may or may not have been intended or even connected to the cards.

Or not. If you and your clientele are served well by a basic understanding, don’t you dare feel intimidated by others who claim you should know more to be a “real” Tarot reader.

I have a passion for Tarot, both as art and method. I have spent many years working with it, reading about it, collecting it, and writing about it. At some point in time I am likely to make one or more decks, and possible write a book or two. But you should not look at my example as what is normal or required.

Everyone can benefit from the mental exercises of meditative observation. If you never pick up another card, or have never picked up one, you can still get more out of your life by looking around, paying attention, and trying to puzzle out what meaning it has.

Thank you for coming all the way to the end, here. I know this one was ponderously long, but it is something that needs explanation and example, so I do appreciate your making the effort. Join me next week for another descent into the maelstrom.