When the magician writes as poet or novelist, are we to take his literary works as a veiled grimoire?

It’s not as uncommon as you might think. Crowley, of course, published poems, plays, and other fiction. Although certainly more recognized for his literary work, William Butler Yeats was an enthusiastic member of the Golden Dawn. A. E. Waite and Eliphas Levi were both considered poets as well as occultists, and more modern authors on occult subjects pen fictional works under their own name, myself included.

Alternatively, if the magician writes as poet or novelist, are we to take his occult works as fraud? This is an unfortunate tendency by those looking to debunk. But the non-believer just sees it as evidence that he was right all along. What about the believers? As those who practice various occult disciplines, does the appearance of a fictional occult novel penned by a known occultist make the ground slippery?

It’s not unfair to say that there is a history of fraud within the occult. Orthodoxy, of course, has it’s own share of charlatans and money-changers violating the temple. It is only reasonable to consider that any spiritual or supernatural belief is likely to attract con-artists. After all, traffic with the unknown and invisible is easy enough to claim.

When we look at the cyclic flowering of interest in magic and spirituality, we see a trend. Prominent figures intermingle with the intellectual and artistic celebrities of the day. Said celebrities often are dabblers themselves- certainly they are drawn to it. Pixie Smith worked in the theatre with Bram Stoker. Her works were exhibited by Alfred Stieglitz, and admired by Georgia O’Keefe. That she is responsible for the most widely know modern Tarot deck seems a minor footnote.

Believer’s see her work as inspired by esoteric powers. It certainly gives life to Waite’s text, and allows us to explore beyond it. And this is true of the works of many artists that use magic, myth, and spiritual dimensions as part of the creative process.

Austin Osman Spare is cited as instrumental in the foundation of Chaos Magic but this was secondary to his career as artist and illustrator in his lifetime, at least in context of the wider public. It is with the hazy fog of time that his magical workings have gained more prominence. I first encountered him through his art, which resonates very much with my own personal tastes and style. I could clearly see the inclusion of occult subject and symbolism, but then I know what I am looking at. An untrained eye will just see “spooky pictures”. I have heard that applied to my work as well.

But I am also trained with the eye of an artist and a good-sized library of art history books and I can think of numerous examples of symbolic art using occult imagery that has little, if any relation, to the artist’s personal spiritual belief. So if I am looking at an overtly occult piece, I don’t automatically assume that the artist is actually involved in the occult.

Nor am I likely to assume that if someone is an open follower of spiritual disciplines, that their creative output is an overtly spiritual act. As an artist, myself, I can speak to this being a very confused landscape. While every work I make has some infusion of will, intention, and perhaps even symbol and construction derived from magical sources, they are not all works of magic. A painting is not a spell, nor is it necessarily enchanted.

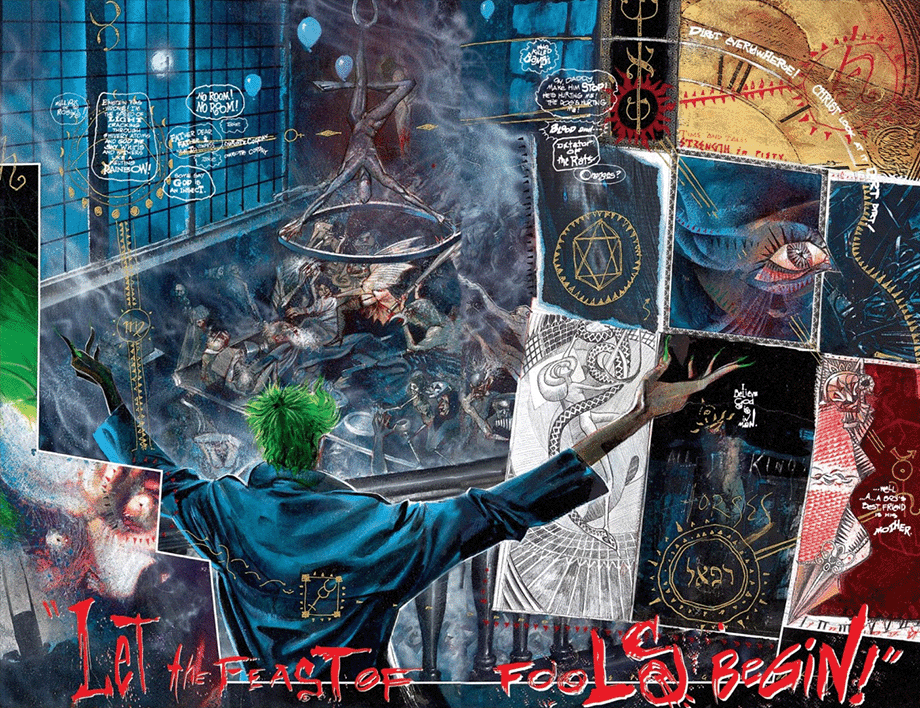

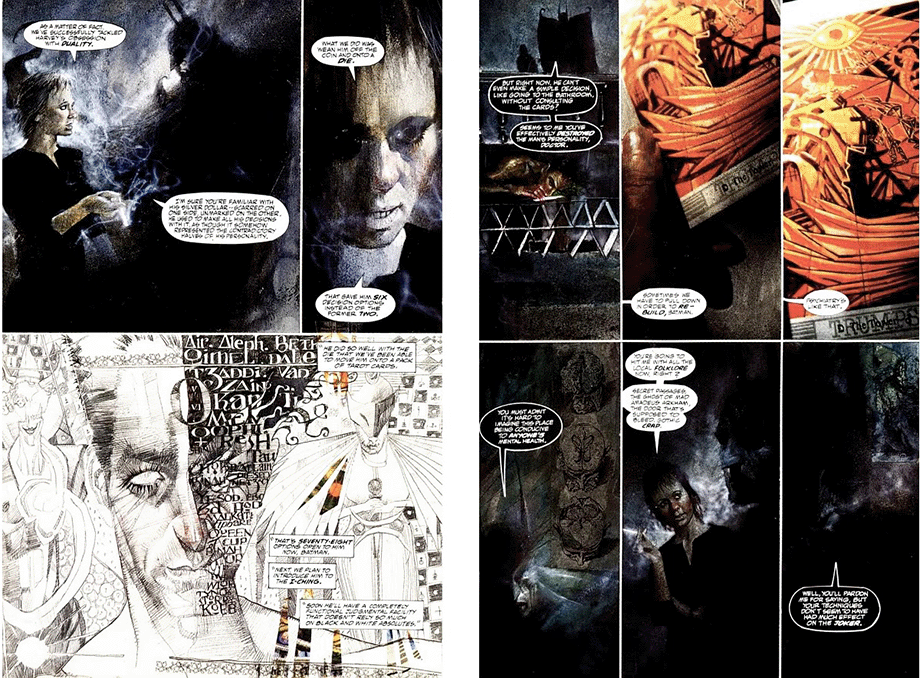

Supposedly the author (who is openly involved in the occult) and the artist (who uses occult symbols but is officially an atheist) were somewhat at odds during the creation of this piece. Perhaps it was this strife that resulted in such a unique and enduring episode in the multi-faceted Batman genre. The image above incorporates a number of familiar occult symbols, such as the Hanged Man and The World from the Thoth Tarot, astrological symbols, Hebraic and Kabbalistic ideograms, Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica and other scribbles and scratching fit for the finest Medieval grimoire.

On the other hand, anything that partakes so profoundly of my own inner spirit, cannot but be charged with it. So a painting does have some power about it. This magic is separate from incantation or ensorcelment. It is creative energy made manifest, and in being that, perhaps is even more richly imbued with that power than an actual intentional work of magic.

It’s a question for philosophy majors and not artists or magicians. As both of the latter, I am in a unique position to appreciate the works of the artist/magician. The artist looks at the work and sees only the art. The magician looks at the work and sees only the symbols. And the rest of humanity just sees the spooky picture. Maybe they are drawn to it or repulsed by it, but their connection is, to my mind, a lesser one.

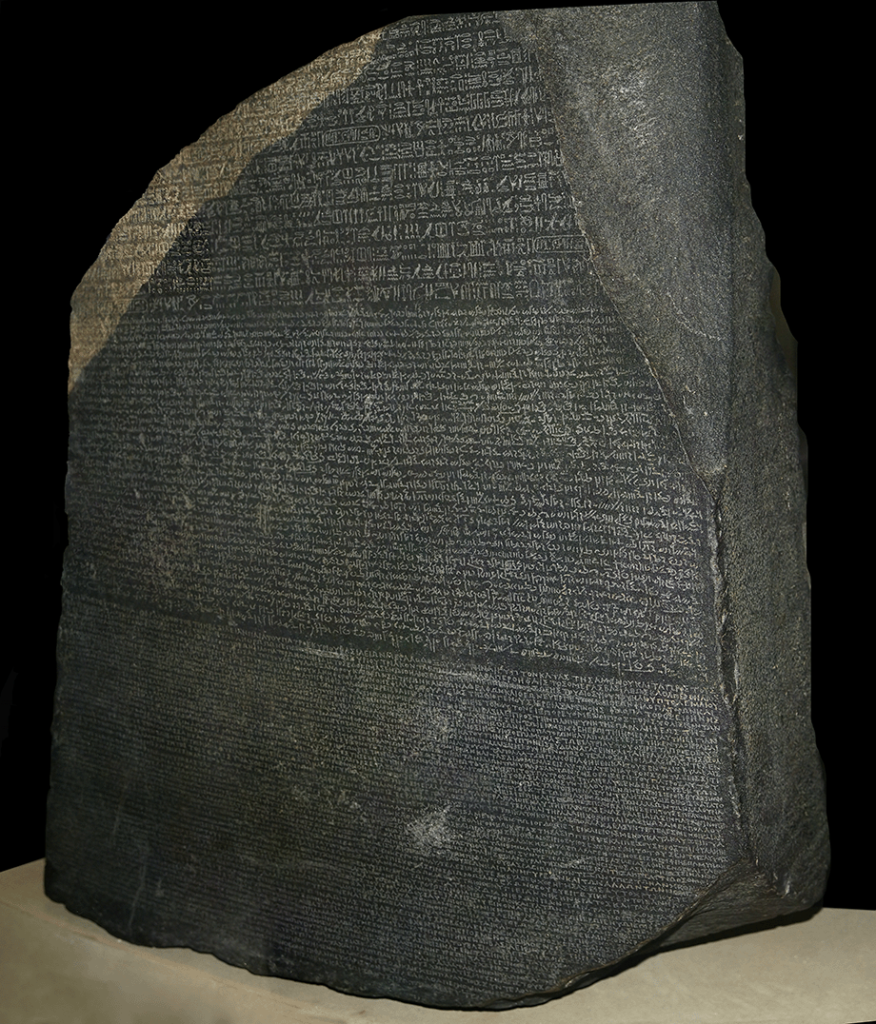

The fusion of mythology and creativity is by no means a new one. The great masterpieces of the Renaissance are taken from both the Judeo-Christian teachings and the tales of the ancient Greeks and Romans. The Roman arts copied the Greeks, and the Greeks were influenced by the Egyptian, Persians, and possibly even Hindus. The magic and the art flowed together, as it always had, since those first scribblings on the walls of Lascaux and Alta Mira caves.

It is only recently that the distinction between art made for sacred purpose and art made for commercial purpose has diverged. It’s part of that secular humanism of the Renaissance.

While it is true that the ancients plopped down their denari at the idol store in the forum for the same kind of mass produced imagery that lines the shelves at your local occult shop, they did not see this as reducing it’s sacred nature.

Ancient peoples understood that the gods lived in every idol, whether carved in finest marble by Phidias for the Acropolis, or poorly modeled in clay by slaves in a foreign port. The magic was in the talisman, whether you paid dearly for it at the temple, or got it from a street vendor outside the bath or brothel.

The craft of the magician, the priest, the witch, and the sorceror were seen as an equally valid career in ancient times. Although the spread of Christianity and later Islam would do a great deal to make those careers socially unacceptable, illegal, and evil, they more or less continued to operate. The Black Books of the Middle Ages simply adopted the monotheistic deities as the inscrutable source of all that was. Angels and demons were at His command, so the sorceror simply used God to bully them into doing his will.

But when we get to the Renaissance and start questioning the nature of that God, the nature of Nature, and the nature of the human role in it, sacredness begins to disappear. Yes, there are certainly spiritually inspired works of art from this period. They are some of the more famous and celebrated works of all time.

But we talk about Michelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling, not God’s, or even the Popes. The focus has shifted to the individual, the personal, away from the divine. While architects had apprenticed in the ancient traditions of Sacred Geometry that drove ever higher the great Gothic cathedrals, they eagerly sold these secrets to build palaces for a new merchant elite, who wielding power and wealth from their own achievement, rather than a heavenly mandate.

By the time we get to the Industrial Revolution, machines are making the art and craft. This triggered several artistic movements aimed at reclaiming the sacred and mystical nature of art, as well as making art a vehicle to communicate these ideas. The Pre-Raphaelites are a strong example of this, using classical and mythical themes in recurring tableaus.

One of my favorites of this period is John William Waterhouse, whose use of Greek and Arthurian myth is ripe with resplendent examples of magical practice, paraphernalia, and iconography. Yet there is no evidence that Waterhouse had any direct experience of occult practice, despite being a contemporary of Waite and Crowley.

Waterhouse was working with a vocabulary common the people in his movement, whose meanings were symbolic, but perhaps more philosophically than spiritually so. The Crystal Ball and Destiny are virtually the same painting, with the same model in the same pose, and communicating a similar idea. But the eponymous crystal is not seen to be a symbol of magic, but of the ideation of future time.

Of secondary consideration is that the Pre-Raphaelites and related movements were very obsessed with the richness of surfaces. The figures exist in complex drapes, flowing dresses, shining armor, reflected in glass and water. There are wide varieties of flowers and plants rendered in accurate detail. Furniture and artifice are exquisitely designed.

The shoes cast aside indicating that this is a sacred space.

The single candle symbolizes the presence of God.

The little dog is code for fidelity – marital faithfulness.

The bed to the right foretells the consummation of the marriage.

Her “pregnant pause” is symbolic of the children she will bear.

Her domestic role is heralded by the little broom on the bedpost.

The figure of St. Margaret on the bedpost offers protection to expectant mothers.

The mirror is surrounded by images of Christ’s passion, indicative of the piety of the couple. This is enforced by the rosary next to it.

The red bed curtains and chair drape represent the Blood of Christ (a source says it’s symbolic of romantic passion but that seems out of place with all the other religious symbology).

The chair itself is topped by a pair of carved cherubim (in the Old Testament sense- the winged bulls of Babylon.) The chair may represent the Throne of God or the “Mercy Seat” on the Ark of the Covenant, which was flanked by two such creatures. The lion on the chair arm may be connected to St. Mark.

Her shoes are closer to the Throne and red. The exposed part of her dress is blue. These are indicators that she is a virgin, and identified with the Holy Virgin Mary.

The green in her robe is further indication of fertility.

His black robes indicate sobriety and dedication.

The hat is another marker that this is taking place in a holy space.

The apples on the left are said to represent original sin. Tangentially, they may also represent the “fruit” of that sin. Much of this painting is about the getting of offspring.

The window indicates that the man is connected to the outside world, whereas his wife (at this time in history) was given dominion over the household only.

The truly interesting part of this, however, is the fact that there is a snuffed out candle over the bride’s head. Though this purports to be a painting of an actual event done at the time, she was dead by the time it was finished.

This emphasis on surface can be found in the late Medieval works in northern and central Europe, notably the painting of Jan Van Eyck. Van Eyck’s most famous painting is The Marriage of Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife. It is a study in esoteric symbolism, and also a marriage license. The painter’s signature indicates he was present to witness the wedding vows, and in fact, he is reflected in the mirror at the back of the room.

Van Eyck was employing a number of sacred codes that would have been familiar to viewers of his day, but this doesn’t mean that he had any specific religious intention in crafting this portrait. As noted in the caption above, Arnolfini’s wife did not live to see it, so it may be a memorial as much as a marriage certificate.

Michelangelo was by most reports a devout Catholic, yet he created imagery that celebrates humanity more than heavenly forces. His works and those of his contemporaries shifted the focus away from a constant piety to a more worldly mindset. The impetus for this movement was the reintroduction of classical Graeco-Roman art and literature through the ports of Venice and the Moorish Kingdom of Cordoba.

Among these works were translations of Ptolemy, the various Greek Magical Papyri, and the Ghayat Al-Hakim – translated into Latin as the Picatrix. The roots of the Tarot probably came by the same route. Fascination with magic and astrology went hand in hand with the philosophy of Aristotle and the science of Archimedes. These were new exotic ideas that had been “lost” during the Dark Ages, and were lustily embraced by those who had survived the Black Death and prospered in the New World Order. Maps of the world now listed many terra incognita and the potential that strange beings and powerful forces lay just beyond the horizon was a very real thing.

As I have mentioned before, the flowering of secular humanism did not go unchallenged by the orthodoxy of the Church. The Renaissance and the years following it were some of the bloodiest in human history, as the establishment sought to maintain control over a population through the Witch Trials and the Holy Inquisition. These paranoid reactions spread to the New World, as well, and have left a stain on our heritage comparable to the Holocaust.

This stain perpetuates today when people characterize anything with a touch of occultist mysticism as “the work of Satan!”. Art, music, and literature that employ the symbolism of spirits, ghosts, deity, and mythology comes under fire as being infernally inspired and corruptive of the consumer. Yet sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

I like fantasy imagery, like the works of Frank Frazetta, Michael Whelan, and Bernie Wrightson, to name only a few. I am equally interested in Salvador Dali, Gustav Klimt, Alphonse Mucha, Frida Kalo, Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Eugene Bernan, all of whom are considered “real” artists as opposed to “illustrators”1But that’s another show.. Am I drawn to this imagery because it has a mystical context? Probably so. But, I have no idea where that yen came from. I have always been more interested in the wild and incredible. This drew me to the works of authors like Tolkien, Zelazny, Herbert, White, and Poe. While these works and the attendant imagery and films certainly informed my awareness of mystical and occult materials, the desire to explore it was always there.

I still locate the occasional tidbit of lore or discover a different approach to a certain magical procedure from works that are technically fiction. Sometimes I am reminded or inspired by things that are not, in their intention, designed to have a mystic quality.

So, at least from where I stand, not all works by a magician are intended to be magic, contain mystic revelation or coded secrets, or be anything other than a work of art. And in that context, it doesn’t reduce the respect I have for the magician in any way. All of us do things to gain our daily bread that are not necessarily connected to our spiritual universe (whether we wish it were or not).

I have so many such irons in the fire. Some are magic oriented, like this blog. Some are just art, and some fall somewhere in between. I try to view what other practicioners and creatives do with a similar eye. I encourage you to consider it. We can but gain access to a wider world.

Thank you for reading to the end. I will be back again next week with more or less obtuse obfuscations.