Well, I understand that today or tomorrow is Imbolc. Or Imolc. Or Imolg.

I must confess that until recent times, this was not an observance I was too keenly aware of, apart from it being Groundhog Day, of course.

In my younger days, absent access to all the books that are abundant now, and with no computer network whatsoever, let alone all the various flavors of Internet, I had only a couple of sources for what were Sabbats. They referenced the Equinoxes, the Solstices, the Eve of All Hallows, and Walpurgisnacht.

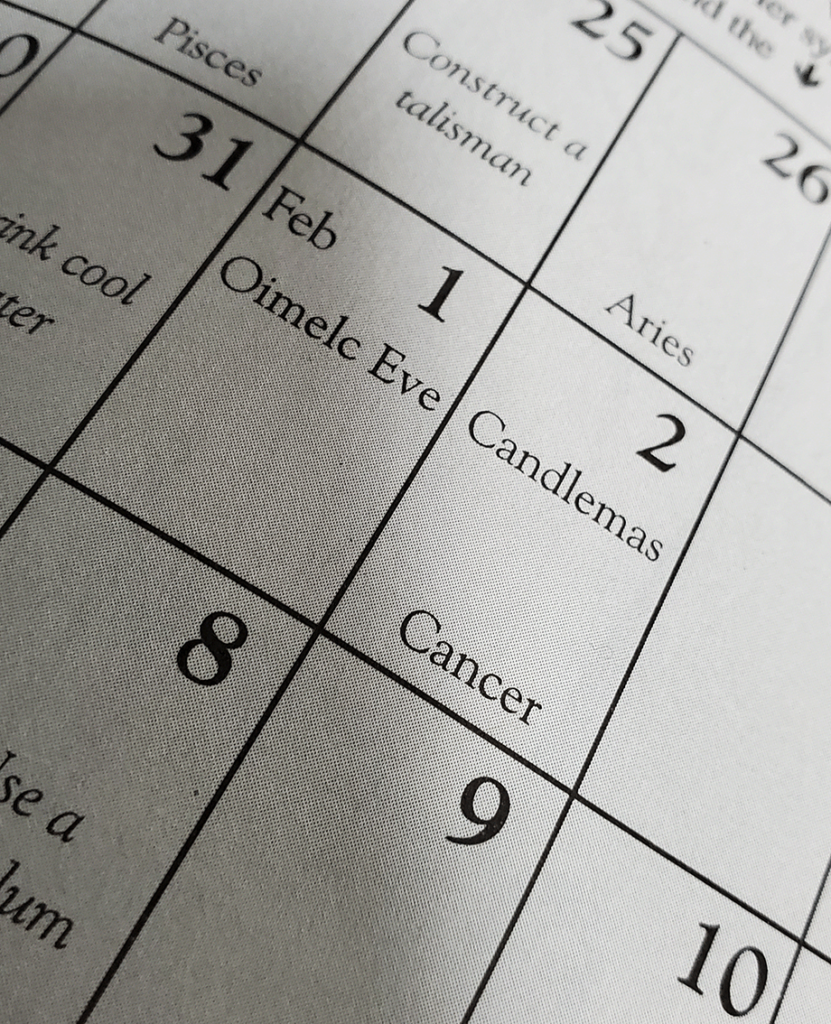

The “Cross-Quarter Days” midpoint between Solstice and Equinox were not enumerated in my references, as they are now in the typical Wheel of the Year. Of course, as I pointed out in my birthday article, we are not really celebrating the Cross-Quarter Days on the astrological day, because the day that sun enters the 15th degree of Aquarius is February 3rd. At least by my charts.

No matter, I am willing to adapt and expand. As I write this a week or so ahead, I am already seeing the Imbolc posts popping up on Instagram and the other social media sites. Which got me going down that ol’ web-search rabbit hole looking for “ye rightwise and true knowledge” of the festival of Imbolc, or Imolc, or Imolg, or…

Well, you see where this is going.

You’ll note that February 2nd here recognizes the Catholic Candlemas, even though it is probably a “stolen” feast day from the old pagan practice. One of the things I like about the Witches Almanac is the pantheist approach of the editorial staff. Catholic witches are a thing. Christian witches are a thing. And if you want blessed candles to bring luck and light in midwinter, what’s the harm. You can always bless them yourself.

I found at least three separate observances (excluding the one largely invented by the Punxatawney, PA Chamber of Commerce) that share the date of the first or second day of February. They are the old Irish tradition of Imolc, the similar old Irish tradition of St. Brigid’s Day, and the also old Irish Catholic tradition of Candlemas, which appears to be an even older Hebrew tradition relating to the Nativity.

So lets work backward here. Candlemas is a Catholic feast day celebrated 40 days after Christmas. It supposedly recognizes the day that baby Jesus was presented to the priests of the Temple in Jerusalem, as part of specific Hebrew ritual. Per the internet, a newborn must be brought into the Temple 40 days after the bris ceremony (the circumcision) and becomes part of the congregation. It is also at this point that the mother is considered to have been ritually purified following birth.

Like many of the ancient Hebrew practices, we can find certain logical precedents for the ritual dates. Forty days is a sacred number in the Old Testament. The Flood was 40 days and 40 nights, for instance. In the New Testament, Jesus spends 40 days in the wilderness, where he faces the temptations of Satan. This can be seen as a specific period of ritual purification as well.

But let’s consider this in the context of the Mother Mary, who was in medieval Europe much more associated with Candlemas than the specifics of the Presentation. Forty days would presumably be long enough for a woman who had given birth to have at least one full menstrual cycle. This would not only signal her return to fertility, but also that any remains of the birth process had be ejected with her menses. This is a reasonable hygienic consideration in ancient times.

In similar fashion, forty days would mean the circumcision of the male child had time to heal, before introducing it to a large group of people and the potential of infection. What perhaps began as basic practices to insure the health and safety of the community, became ritualized in order to perpetuate their practice.

But in medieval Europe, where the practice of circumcision was rare, and Hebrew ritual was not as much a part of the Christian service, these things became dogma. We celebrate this because we do. Yes, there was a meaning, but you don’t need to know that.

And, well, we also need some reason to continue practicing this pagan holiday in the middle of the cold months so we can get more people converted over to the One True Way and all that.

Which brings us to Imolc and St. Brigid. These seem to have survived in Ireland more than in other Celtic regions. There is every indication, however, that a day in early February also had significance in the Teutonic and Anglo-Saxon cultures of central Europe, and may also have been known in Scandinavia. It is most likely that this has more to do with preparing for the agricultural duties of the coming spring.

Imolc is generally roughly translated as “in the belly” and is believed to refer to the pregnant ewes among the all-important sheep of the ancient Irish economy. This getting of the lambs could vary a week or so around the first part of February, but essentially this meant that the sheep would be born about the time that the first grasses were cropping up in the meadows around early to mid-March. This is the point usually when the last hard freeze is past, and planting of the crops can begin, so the pregnant sheep were a good time marker for preparing the seeds, fixing the plows and other farm equipment, and generally shifting from the winter inactivity, to the spring activity.

St. Brigid, the “Mary of Ireland”, is a semi-mythical personage who may have been named after a more ancient goddess Brigid or Bride (and is possibly synonymous with the Welsh Rhiannon, and Gaulic Brigantia) .

The goddess Brigid was one of the Tuatha de Danaan – the People of Donn, which are frequently viewed as elves or faeries. She may have been a triple goddess, or a goddess of triple aspects, but she is identified with poetry (and thus spellsinging or magic) blacksmithing, healing, and livestock. So her feast day celebration on or around the time of Imolc makes much sense as it ties to the activities needed for the approach of spring.

St. Brigid of Kildare is supposedly the daughter of a nobleman and a pagan slave. She was released from her bondage due to her charitable nature tipping off the High King to her special purpose. She is purported to have founded the first convent in Ireland at Kildare, under an ancient sacred oak, thus usurping the old Druid Magic with a new Christian Faith.

She seems to have borrowed a good deal of her namesake’s mythology, but this is not unusual for an early Christian saint whose celebrations are plastered over an ancient pagan feast day. In Ireland which embraces and transformed the Roman Faith into something uniquely Celtic, the gods and heroes march dutifully into sainthood and remain preserved for us. Their continental counterparts were not as fortunate.

So Brigid the goddess and Brigid the Christian saint merged and continued to herald the coming of spring, and through her role as “Blessed Virgin of Ireland” comfortably supplanted Candlemas in the Irish liturgical calendar.

Or so the internet says. But here I am, still trying to figure out where the groundhog came from.

The question here, of course, if whether the Great Floofy One will mistake the House Panther for his shadow and I will be stuck underneath the pair of them for another six weeks.

I guess it could be worse. If it is a longer winter, at least I will stay toasty warm with all that hair.

Yes, I know. The groundhog really isn’t part of the old traditions. Or at least it doesn’t seem to be. But I have that obsessive nature that drives me to look for connections in these things. If a tradition survives on or about the same day as some other tradition, there is some likelihood that they are linked. And I am that guy that just has to know.

Especially if I am trying to work out how any and all of these traditions fit into my own practice and world view. I am not someone who can just accept that we celebrate this day because we do. It needs to mean something to me personally, or I just won’t do it.

So the groundhog apparently is another one of those Pennsylvania Dutch – nee Deutsch things. It survives from a practice in Germany where the local critter was a badger, though the tradition remains the same. If it comes out on a sunny day in early February, winter is going to last another six weeks…which gets us on into April.

Of course, if it’s cloudy and murky on February 2nd, then we get an early spring.

I find this to be counter-intuitive, and I can’t be the only one.

To me, if we’re going by the usual signs and portents, a sunny day would surely mean that spring is on the way. Also, if your local furry critter pops out of it’s burrow on such a day, that would indicate it is no longer in hibernation and that the worst of winter is likely over.

So why should these two signs taken together be considered a sign of six more weeks of cold nasty weather.

My initial thought was that we might be dealing with a proverb type situation such as “counting the chickens before they hatch”. That is, seeing the sun shining and the little beasties out and about in early February was just too good to be true. Best prepare for things to remain bleak for a bit longer, and take the time to lay in more supplies.

Turns out that last bit might be the key to the whole thing. Sort of.

In my digging I ran across another ancient Celtic goddess. Called the Cailleach among other names, she is the “Old Woman of Winter” and seems to occupy a spot opposite Brigid, in the latter’s aspect as goddess of the spring. The Cailleach is the personification of the Winter Dark, the bleak death of the world, the abandonment of the sun, and potentially ruler of nature during the period between Samhain and Beltane.

Being a Winter Dark thing myself, I like her. She’s a goddess I can relate to. Suddenly this thing got a lot more personal.

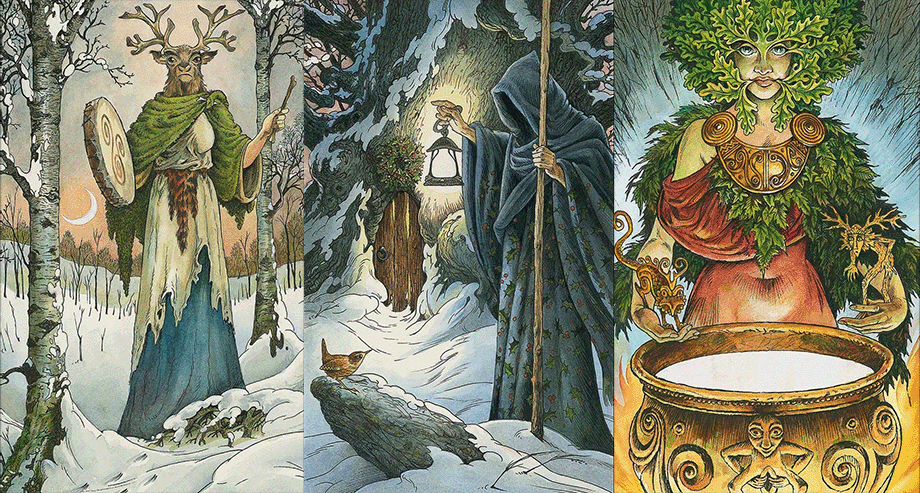

The deck is unashamedly Celtic in character, which fits the Imbolc tradition perfectly. You might be able to puzzle out which cards I have chosen, as some of the iconography is traditional, but the way they have been fit into the Celtic shamanistic tradition that Mr, Matthews and his wife Caitlin have developed so well in the last few decades is unique.

Alas there was not an obvious Cailleach card, and the two here (left and center) both felt right. In the parlance of the Wildwood, they are the Ancestor and Hooded Man (Hooded One works as well). They correspond to the more usual Hierophant and Hermit, which I have discussed at length before (and which I frequently associate with my own sometimes larger-than-life persona). They are connected concepts, and both seem to auger here the presence of Winter Dark.

Even though the Ancestor is out in broad daylight, the moon is visible, and the bleak sky portends more snow may be coming. This being reflects the great gulf of time that separates us from our origins, from the known into the unknown, from the dimming light into the apparent continual darkness.

Offsetting them in the role of Brigid/Rhiannon/Brigantia is the Green Woman, apt for a goddess associated with spring arriving. In the deck she corresponds to the Empress, which is also appropriate, with her connection to the fecundity of Venus and matters of birth and fertility in animals and plants.

I cannot recommend this particular deck highly enough, especially for those of us with Celtic roots, or who are pursing a path of nature-based paganism. The imagery alone is worth the price, and the accompanying book is insightful and innovative.

In any case, depending on local tradition, the transition from the Old Woman to the Young Brigid was celebrated on different days. Beltane was an obvious one, because by the first of May any vestige of winter’s grip was well and truly gone.

Practically of course, spring activities begin well before May 1st. The whole month of April is usually occupied in planting and lambing, if not earlier, so another date for the hand-off was around March 25, which is close enough to the Vernal Equinox to argue that as the intended date, plus or minus several years of calendrical confutation.

And still one other tradition takes us all the way back to Brigid’s Day on February 2nd.

While this ties us neatly into Candlemas, Imolc, and St. Brigid, I am sure you are wondering what happened to the groundhog.

Well, it’s not so much the groundhog (or the badger), but the day.

See according to one Scottish tradition, the Cailleach would go out on February 2nd to gather wood in for the rest of winter. Because she was a most powerful witch, she cast a spell for a sunny clear day so that she would not be inconvenienced by poor weather while getting in her provisions.

And thus if February 2nd is bright and sunny, we know the Cailleach is prepared to deliver winter weather on into mid-April. That was the part of the equation I was looking for.

Okay, so I still don’t know where the badger fits into that. But, hey, we don’t need no stinking badgers.

In the early morning hours today, as I was between being asleep and reaching full wakefulness, I was thinking about needing to write this article. An image came into my mind unbidden, as it does sometimes during that hypnogogic state that is not really thinking and not really dreaming, where the subconscious just bubbles things up.

It was a brief vision (if you will) of a small household altar, with the remains of a human skull among the other accoutrements, and the owner’s hand gently stroking it. Through that metadata that accompanies such experiences, I knew that this was the skull of an ancestor, kept reverently and lovingly addressed.

Now, because I do have that obsessive faculty, I can suggest that perhaps this drifted up because in my research I discovered that portions of a skull believed to be that of Brigid of Kildare are scattered across Europe, where they are venerated in various churches and cathedrals. I think perhaps a little piece may have returned to her native Ireland, which seems kind of sad, because the larger portions remain abroad.

I really have not understood the Catholic cult of the relics. I have always viewed it as an economic engine, wherein a particular site was given or recognized as having an object of veneration and power in order to attract pilgrims and their gold. Yes, I am a cynic. I can make the same argument for the sacred wells of the Celtic world, the various Oracles in Greece, and the numerous temples along the Nile. There is and always has been a mercenary component to the practice of ritual and religion.

But that does not, and should not take away the spiritual nature of such a pilgrimage, or the belief in the power of the venerated object or location. I think perhaps that ancestor skull in my early morning vision is a kind of epiphany for that. What we connect to, and hold dear, and revere, is powerful, if for no other reason than that we imbue it with our own power.

I don’t know that many of us have the bones of our ancestors. Some of us, if not most, may have the opportunity to visit those remains in a cemetery or mausoleum, but with the rise in cremation the “scattering of ashes” seems to be severing those links forever.

Relationships with the ancestors can be problematic. The ones that we personally knew, were known to us, “warts and all” and as such potentially offer memories of trauma and disfunction. Past grandparents and maybe great grandparents, they exist as photographs and names only, and what limited stories come down to us. Unless they were celebrated or famous, there’s generally not a lot of detail, aside from names on gravestones or maybe in a family Bible.

So perhaps that’s why we connect to myth figures and saints, and attach our rituals to some tangible remnant of their existence in the ever-changing world we inhabit. We need that assurance that something lasts, that spring will continue to follow winter, even as we enter our own personal Winter Dark. We need to believe that the path is a circle and not simply a road that heads out into the wilderness and then abruptly ends.

That is what I found when looking for Imbolc, anyway. This blog is my own personal journey as much as it is anything else. I remain, for now, on the road.

I will be back next week.